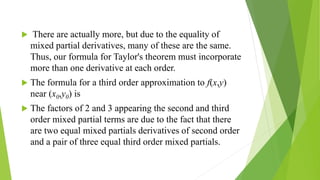

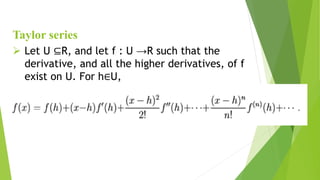

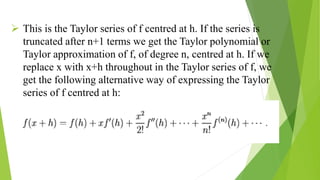

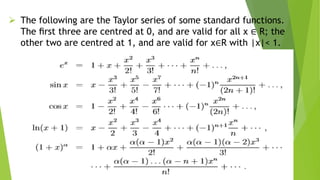

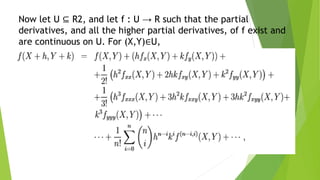

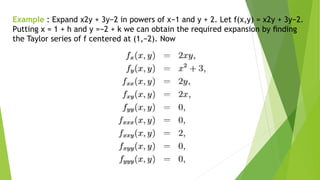

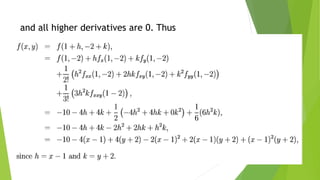

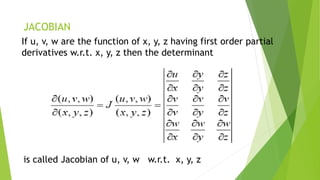

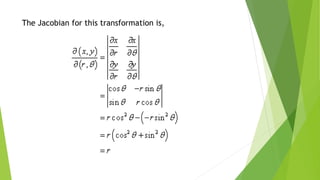

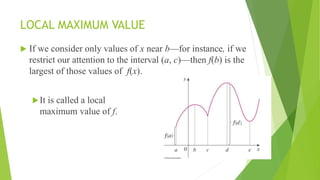

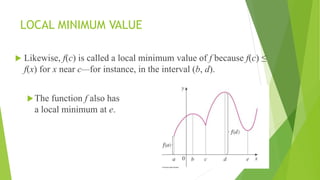

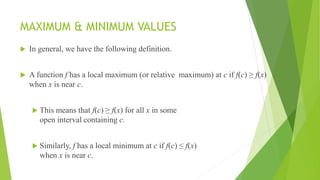

The document covers the applications of partial differentiation in calculus, discussing concepts such as Taylor's theorem for functions of two variables, Jacobians, error analysis, and methods for finding maxima and minima. Key topics include the formulation of Taylor series, the process of approximating functions, and techniques like Lagrange multipliers for optimization under constraints. Examples illustrate the calculation of errors in measurements and extreme values of functions under given constraints.