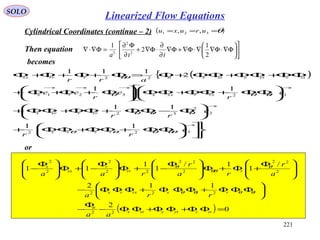

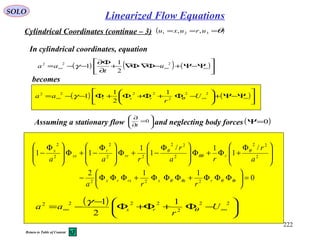

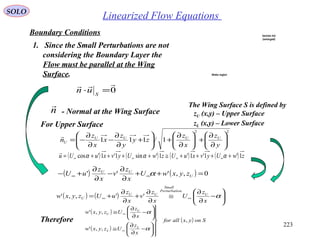

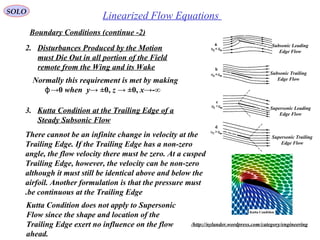

This document provides a table of contents for topics in fluid dynamics. It begins with mathematical notations for vectors, tensors, divergence, gradient, and other vector calculus topics. It then outlines the basic laws of fluid dynamics, such as conservation of mass and momentum. Later sections cover specific fluid dynamics concepts like boundary layers, compressible flow, shock waves, and potential flow. The document provides the framework for equations and analyses of fluid flows.

![9

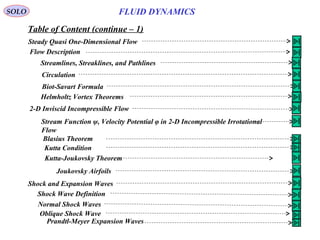

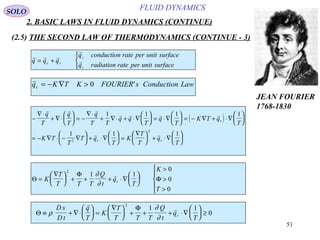

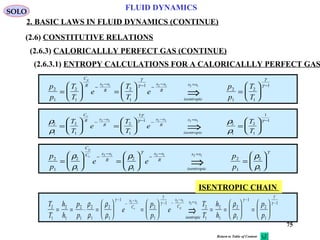

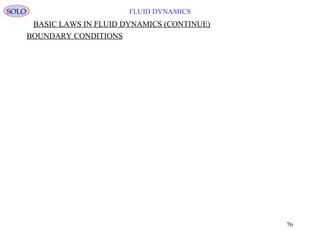

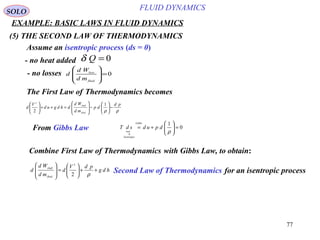

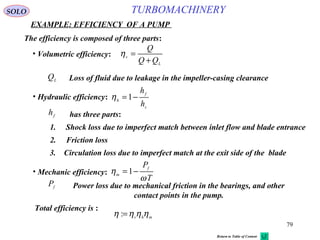

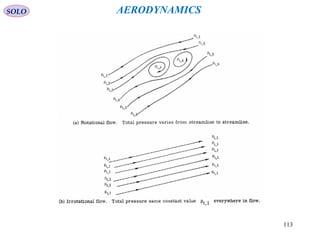

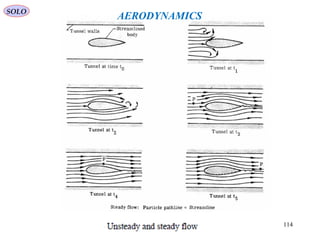

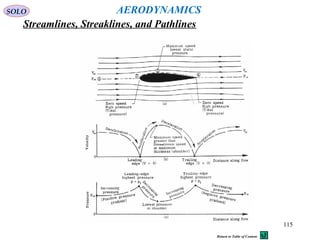

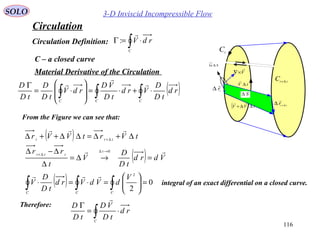

FLUID DYNAMICS

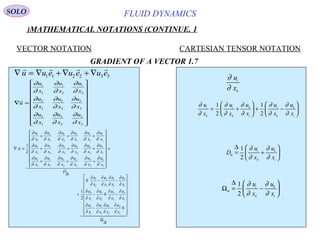

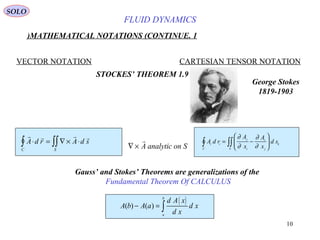

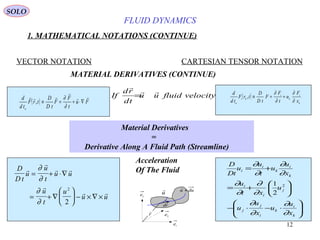

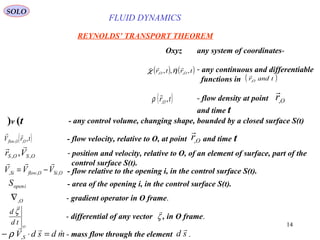

1.MATHEMATICAL NOTATIONS (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

1.8GAUSS’ THEOREMS (CONTINUE)

( ) ( ) ( )∫∫ ∫∫∫ ⋅∇=⋅

S V

dvAsdAGAUSS

ηη3

( )= ⋅∇ + ∇⋅∫∫∫

A A dvη η

η∇⋅∇ ,A

analytic inV

( )η

∂ η

∂

A ds

A

x

dv

V

k k

k

kS

= ∫∫∫∫∫

∫∫∫

+=

V k

k

k

k

x

A

x

A

∂

∂

η

∂

η∂

↓ = + +

B e e eη η η1 1 2 2 3 3

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]∫∫ ∫∫∫ ⋅∇+∇⋅=⋅

S V

dvABBAsdABGAUSS

4 B A ds A

B

x

B

A

x

dv

V

i k k k

i

k

i

k

kS

= +

∫∫∫∫∫

∂

∂

∂

∂

∇ ×

A analytic inV( ) ∫∫ ∫∫∫ ×∇=×

S V

dvAAsdGAUSS

5 ( )ds A ds A

A

x

A

x

dv

V

i j j i

j

i

i

jS

− = −

∫∫∫∫∫

∂

∂

∂

∂

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-9-320.jpg)

![13

FLUID DYNAMICS

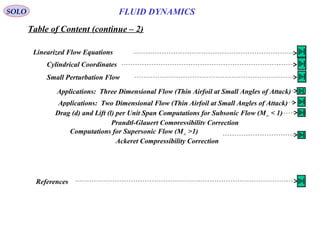

1. MATHEMATICAL NOTATIONS (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

1.10 MATERIAL DERIVATIVES (CONTINUE)

d u

u

t

dt dr u

= + ⋅∇

∂

∂

du

u

t

dt dx

u

x

i

i

k

i

k

= + ⋅

∂

∂

∂

∂

rdrdDtd

t

u

xd

xd

xd

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

t

u

t

u

t

u

ud

ud

ud

ikik

Ω++=

+

=

∂

∂

∂

∂

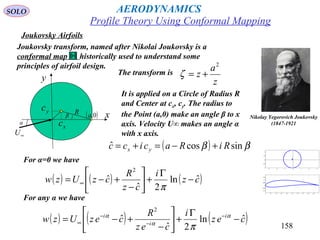

∂

∂

∂

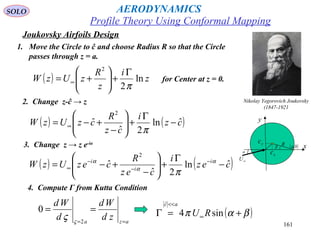

∂

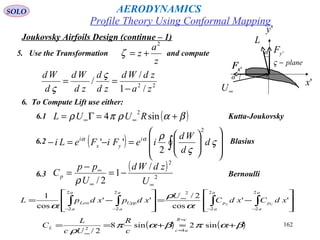

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

3

2

1

3

3

2

3

1

3

3

2

2

2

1

2

3

1

2

1

1

1

3

2

1

3

2

1

d u

u

t

d t

u

x

u

x

d x

u

x

u

x

d x

i

i

Translation

i

k

k

i

Dilation

k

i

k

k

i

Rotation

k

= +

+ +

+ −

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

1

2

1

2

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ] Dilationrduu

rdurdu

urdrdurdu

rdurdurdD

T

u

u

ik

⇒⋅∇+∇=

⋅∇+⋅∇=

∇⋅−⋅∇+⋅∇=

××∇−⋅∇=

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

( )Ωik dr u dr Rotation

= ∇ × × ⇒

1

2

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-13-320.jpg)

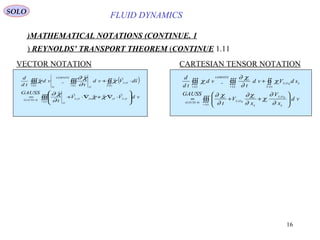

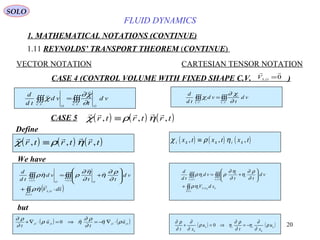

![21

FLUID DYNAMICS

1. MATHEMATICAL NOTATIONS (CONTINUE)

1.11 REYNOLDS’ TRANSPORT THEOREM (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

We have

( )

( )

( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )[ ]∫∫∫∫∫=

∫∫

∫∫∫

∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫∫

⋅−+

⋅+

⋅∇+∇⋅−

∇⋅+=

⋅+

⋅∇−=

+

+

)(

,,

)(

4

.

)(

,

)(

,,,,,,

)(

,

)(

,,

)(

tS

OOS

tv

O

MDG

DerMat

GAUSS

tS

OS

tv

OOOOOO

O

tS

OS

tv

OO

OO

tv

sduVvd

tD

D

sdV

vduuu

t

sdV

vdu

t

vd

td

d

ρηρ

η

ρη

ρηηρη

∂

η∂

ρ

ρη

ρηρ

∂

η∂

ρη ( )

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )[ ]∫∫∫∫∫=

∫∫

∫∫∫

∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫∫

−+

+

+−

+=

+

−=

+

+

)(

,

)(

4

.

)(

,

)(

)(

,

)()(

tS

kkkOSi

tv

i

MDG

DerMat

GAUSS

tS

kkOSi

tv k

k

i

k

i

k

k

i

k

i

tS

kkOSi

tv k

k

i

i

tv

i

sduVvd

tD

D

sdV

vd

x

u

x

u

x

u

t

sdV

vd

x

u

t

vd

td

d

ρηρ

η

ρη

∂

ρ∂

η

∂

η∂

ρ

∂

η∂

∂

η∂

ρ

ρη

∂

ρ∂

ηρ

∂

η∂

ρη

CASE 5 ( ) ( ) ( )

χ ρ ηr t r t r t, , ,≡

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-21-320.jpg)

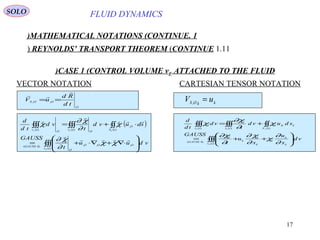

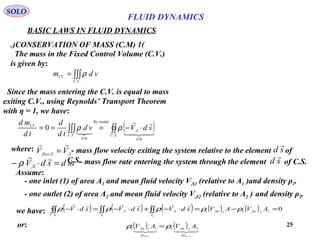

![22

FLUID DYNAMICS

1. MATHEMATICAL NOTATIONS (CONTINUE)

1.11 REYNOLDS’ TRANSPORT THEOREM (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

REYNOLDS 1

( )[ ]

⋅−+= ∫∫∫∫∫

∫∫∫

)(

,,

)(

)(

tS

OOS

tv

O

O

tv

sduVvd

tD

D

vd

td

d

ρηρ

η

ρη

( )[ ]

−+= ∫∫∫∫∫

∫∫∫

)(

,

)(

)(

tS

kkkOSi

tv

i

tv

i

sduVvd

tD

D

dv

td

d

ρηρ

η

ρη

REYNOLDS 2

( )[ ]

=

⋅−+

∫∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫

)(

)(

,,

)(

tv

O

tS

OSO

O

tv

vd

tD

D

sdVuvd

td

d

ρ

η

ρηρη

( )[ ]

=

−+

∫∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫

)(

)(

,

)(

tv

i

tS

kkOSki

tv

i

vd

tD

D

sdVuvd

td

d

ρ

η

ρηρη

CASE 5 ( ) ( ) ( )

χ ρ ηr t r t r t, , ,≡

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-22-320.jpg)

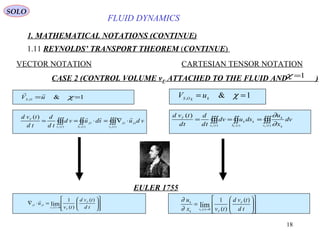

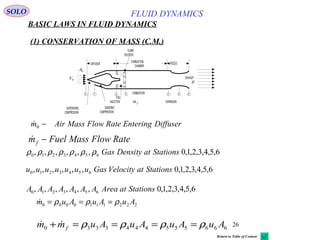

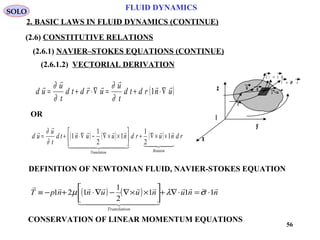

![31

FLUID DYNAMICS

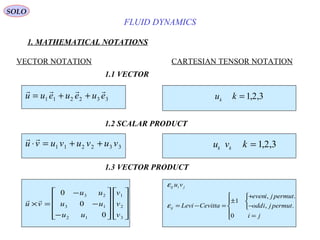

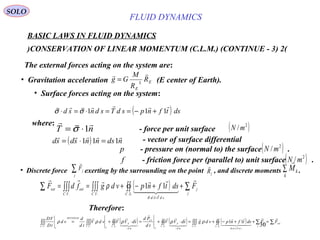

BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.2) CONSERVATION OF LINEAR MOMENTUM (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

C.L.M.-2

Since this is true for all volumes vF(t) attached to the fluid we can drop the volume integral.

[ ] [ ] [ ]τσ

τρσρ

∂

∂

ρ

∂

∂

ρρ

~~

~~

2

1

,,,

,

2

,

,

.).(

+−=

⋅∇+∇−=⋅∇+=

×∇×−

∇+=

∇⋅+=

Ip

pGG

uuu

t

u

uu

t

u

tD

uD

III

II

I

I

I

DM

I

ikikik

i

ik

i

i

i

ik

i

k

i

k

i

j

jjj

i

i

k

i

k

i

DM

i

p

xx

p

G

x

G

x

u

u

x

u

uuu

xt

u

x

u

u

t

u

tD

uD

τδσ

∂

τ∂

∂

∂

ρ

∂

σ∂

ρ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

ρ

∂

∂

∂

∂

ρρ

+−=

+−=+=

⋅−⋅−

+=

⋅+=

2

1

.).(

SOLO

Derivation From Integral Form (Continue)

( )∫∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

⋅∇+=

⋅+=

)(

,

)()()(

,

~

~

tv

I

tStvtv

I

I

F

FFF

vdG

sdvdGvd

tD

uD

σρ

σρρ

∫∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

+=

+=

)(

)()()(

tv i

ik

i

tS

kik

tv

i

tv

i

F

FFF

vd

x

G

sdvdGvd

tD

uD

∂

σ∂

ρ

σρρ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-31-320.jpg)

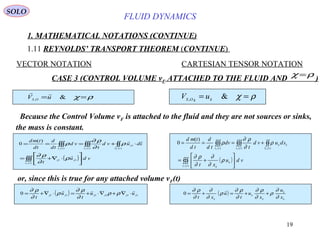

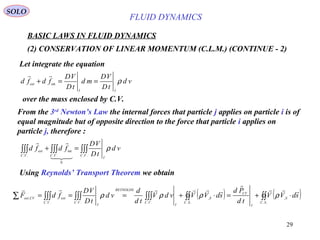

![32

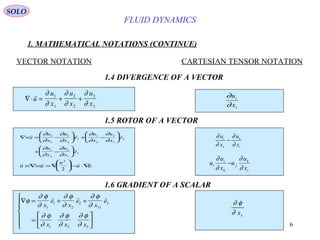

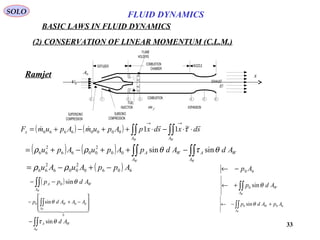

BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS

(2)CONSERVATION OF LINEAR MOMENTUM (C.L.M.)

SOLO

Let compute the C.L.M. in the tangential to the

wheel direction, for the Pelton Water Wheel

( )[ ]

( ) ( )

t

tvtv

extjj RfdfdrVrQVQ −+=−−− ∫∫

0

int

0

cos βωωρρ

where

( ) ( )∫∫∫∫ ⋅−=⋅−=

outin A

S

A

S

sdVsdVQ

,,

: ρρρ

( ) ( )βωρ cos1+−= rVQR jt

Therefore

The average Torque on the water wheel is ( ) ( )βωρ cos1+−== rVrQrRTorque jt

The Power developed is ( ) ( )βωωρω cos1+−==⋅= rVrQrRTorquePower jt

The average Tangential Reaction Force on

the bucket is

In steady-state the directions and

magnitudes of flows are fixed, therefore

0

..

== ∫∫∫

I

VC

I

CV

vdV

td

d

td

Pd

ρ

( ) ( )

∑∑∫∫∫∫∫

∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

=+⋅+=

⋅+=⋅+

−−

ext

j

j

SCVC

SC

md

S

I

CV

SC

md

S

I

VC

FFsdvdg

sdVV

td

Pd

sdVVvdV

td

d

....

..

,

..

,

..

σρ

ρρρ

Example

FLUID DYNAMICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-32-320.jpg)

![34

Ramjet

SOLO

CONSERVATION OF LINEAR MOMENTUM (C.L.M.) (continue – 1)

( ) ( )

DRAGFRICTION

A

WA

DRAGPRESURE

A

WA

THRUST

x

WW

AdAdppAppAuAuF ∫∫∫∫ −−−−+−= θτθρρ sinsin06060

2

006

2

66

00000666 & mAummAu f

=+= ρρUsing C.M.

( ) ( ) 0006060

2

006

2

66 umummAppAuAuTHRUST ef

−+=−+−= ρρ

or

we obtain

( )[ ] ( ) 060600 /:1 mmfAppuufmTHRUST fe

=−+−+==T

and ( )

DRAGFRICTION

A

WA

DRAGPRESURE

A

WA

WW

AdAdppDRAGD ∫∫∫∫ +−== θτθ sinsin0

1 2 30 4 5 6

SUPERSONIC

COMPRESSION

SUBSONIC

COMPRESSION

COMBUSTION

FUEL

INJECTION EXPANSION

NOZZLECOMBUSTION

CHAMBER

DIFFUSER

FLAME

HOLDERS

EXHAUST

JET

0V

0A

fm

x

BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS

FLUID DYNAMICS

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-34-320.jpg)

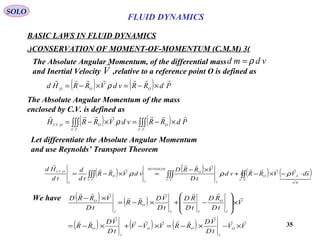

![38

BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS

(3) CONSERVATION OF MOMENT-OF-MOMENTUM (C.M.M.)

SOLO

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

systemoutsidefromexertedTorque

M

l

lz

j

j

tv

ext

AVVrAVVr

SC

S

statesteady

VC

zSnSn

MFrdfrsdVVrvdVr

td

d

∑∑∫∫∫∫ ++=⋅−−

+−−→

θθ

ρρ

θθ

θθ

ρρ

22,21111,122

..

,

0

..

We obtain

( ) ( )[ ] zflow

MQVrVr =− 111122

ρθθ

or

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) zSnSnSn

MAVVrVrAVVrAVVr =−=− 11,1112211,11122,222

ρρρ θθθθ

Euler Turbine Equation

ρ1 - mean fluid density one inlet (1) of area A1.

where

ρ2 - mean fluid density one outlet (2) of area A2.

(Vθ )1, r1 - mean fluid tangential velocity and radius one inlet (1) of area A1.

(Vθ )2, r2 - mean fluid tangential velocity and radius one outlet (2) of area A2.

(V,Sn )1 - mean fluid normal velocity (relative to A1) one inlet (1) of area A1.

(V,Sn )2 - mean fluid normal velocity (relative to A2) one outlet (2) of area A2.

- mean flow rate one outlet (1) of area A1.( ) 11,1 : AVQ Snflow =

Leonhard Euler

(1707-1783)

FLUID DYNAMICS

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-38-320.jpg)

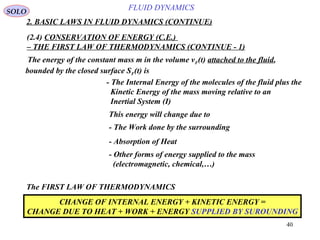

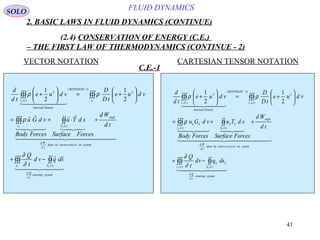

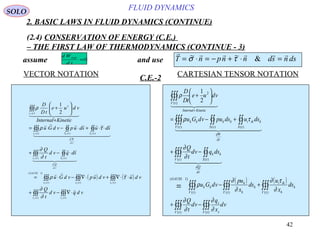

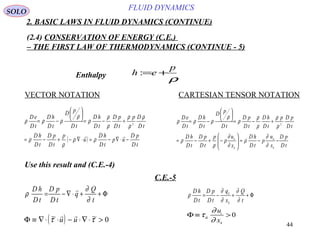

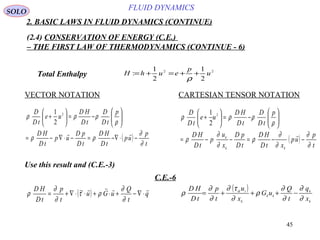

![43

FLUID DYNAMICS

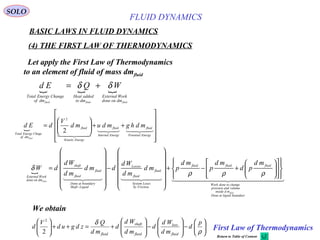

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.4) CONSERVATION OF ENERGY (C.E.)

– THE FIRST LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS (CONTINUE-4)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATIONC.E.-3

Since the last equation is valid for each vF(t) we can drop the integral and obtain:

( ) ( )

q

t

Q

uGuupue

tD

D

⋅∇−+

⋅+⋅⋅∇+⋅−∇=

+

∂

∂

ρτρ ~

2

1 2 ( ) ( )

k

k

kk

k

iik

k

k

x

q

t

Q

uG

x

u

x

up

ue

tD

D

∂

∂

∂

∂

ρ

∂

τ∂

∂

∂

ρ

−+

++−=

+ 2

2

1

Multiply (C.L.M.-2) by

u

τρρ ~⋅∇⋅+∇⋅−⋅=⋅ upuuG

tD

uD

u

( )

k

ik

i

k

kkk

i

i

x

u

x

p

uuGu

tD

D

tD

uD

u

∂

τ∂

∂

∂

ρρρ +−== 2

Subtract this equation from (C.E.-3)

C.E.-4

( )[ ]ρ τ τ

∂

∂

D e

D t

p u u u

Q

t

q

= − ∇⋅ + ∇⋅ ⋅ − ⋅∇⋅

+ −∇⋅

~ ~

Φ

ρ

∂

∂

τ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

D e

D t

p

u

x

u

u

x

Q

t

q

x

k

k

ik

i

k

k

k

=− +

+ −

Φ

( )Φ ≡ ∇⋅ ⋅ − ⋅∇ ⋅ >~ ~τ τ

u u 0

Φ ≡ >τ

∂

∂

ik

i

k

u

x

0

(Proof of inequality given later)

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-43-320.jpg)

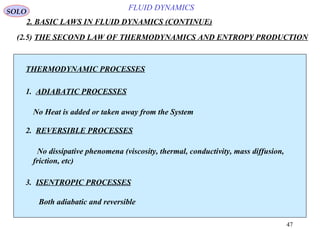

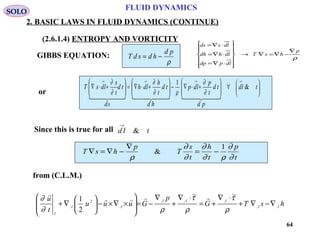

![48

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.5) THE SECOND LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS AND ENTROPY PRODUCTION

2nd

LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS

Using GAUSS’ THEOREM

0

)()(

≥+ ∫∫∫∫∫

tStv FF

Ad

T

q

vds

td

d

ρ

00

)(

)1(

)()(

≥

⋅∇+⇒≥+ ∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

tv

GAUSS

tStv FFF

vd

T

q

tD

sD

Ad

T

q

vd

tD

sD

ρρ

- Change in Entropy per unit volumed s

- Local TemperatureT [ ]K

- Fluid Densityρ [ ]3

/ mKg

d e q w T ds pdv= + = −δ δ d s

d e

T

p

T

dv= +

SOLO

For a Reversible Process

- Rate of Conduction and Radiation of Heat from the System

per unit surface

q

[ ]2

/ mW

Gibbs Relation

Josiah Willard Gibbs

(1839-1903)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-48-320.jpg)

![54

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS FOR GASES

(2.6.1) NEWTONIAN FLUID DEFINITION – NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS

[ ] τσ ~~ +−= Ip

Stress

NEWTONIAN FLUID:

The Shear Stress on

A Surface Parallel

to the Flow =

Distance Rate of

Change of Velocity

SOLO

CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

ikikik p τδσ +−=

VECTOR NOTATION

- Stress tensor (force per unit surface) of the surrounding

on the control surface ( )2

/ mN

σ~

- Shear stress tensor (force per unit surface) of the surrounding on the control

surface ( )2

/ mN

τ~](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-54-320.jpg)

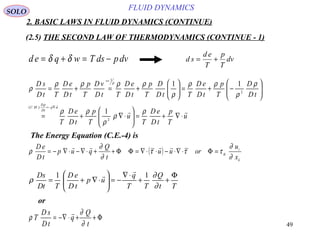

![55

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NEWTONIAN FLUID DEFINITION – NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS

M. NAVIER 1822

INCOMPRESSIBLE FLUIDS

(MOLECULAR MODEL)

G.G. STOKES 1845

COMPRESSIBLE FLUIDS

(MACROSCOPIC MODEL)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

[ ] [ ] ( )[ ] [ ]IuuuIpIp

T

∇+∇+∇+−=+−= λµτσ ~~

ik

k

k

i

k

k

i

ikikikik

x

u

x

u

x

u

pp δ

∂

∂

λ

∂

∂

∂

∂

µδτδσ +

++−=+−=

( )[ ] [ ]( ) ( ) ( ) µλλµλµτ

3

2

32~0 −=⇒∇+∇=∇+∇+∇== utrutrIutruutrtr

T

( ) µλ

∂

∂

λµδ

∂

∂

λ

∂

∂

µτ

3

2

0322 −=⇒=+=+=

i

i

ik

k

k

i

i

ii

x

u

x

u

x

u

SOLO

STOKES ASSUMPTION µλ

3

2

−=0~ =τtrace

μ, λ - Lamé parameters from Elasticity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-55-320.jpg)

![58

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

I

x

y

z

T n= ⋅~σ

d s n ds=

r

dru

u + du

THEREFORE

( ) ( ) ( ){ }∫∫∫∫∫∫ ⋅∇∇+×∇×∇−⋅∇∇+∇−=

)()(

2

tVtV

vduuupGvd

tD

uD

λµµρρ

OR

( ) ( )[ ]uupG

tD

uD

⋅∇+∇+×∇×∇−∇−= µλµρρ 2

SOLO

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS (CONTINUE)

(2.6.1.2)VECTORIAL DERIVATION (CONTINUE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-58-320.jpg)

![59

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

VECTOR NOTATION CARTESIAN TENSOR NOTATION

CONSERVATION OF LINEAR MOMENTUM

( ) ( )[ ]∇ ⋅ = − ∇ − ∇ × ∇ × + ∇ + ∇ ⋅~σ µ µ λp u u

2 ( )

++

++−=

k

k

ii

k

k

i

iii

ik

x

u

xx

u

x

u

xx

p

x ∂

∂

λµ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

σ∂

2

( ) ( )[ ]

ρ ρ σ

ρ µ µ λ

Du

Dt

G

G p u u

= + ∇ ⋅

= − ∇ − ∇ × ∇ × + ∇ + ∇ ⋅

~

2 ( )

++

++−=

+=

k

k

ii

k

k

i

ii

i

i

ik

i

i

x

u

xx

u

x

u

xx

p

G

x

G

tD

uD

∂

∂

λµ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

ρ

∂

σ∂

ρρ

2

USING STOKES ASSUMPTION tr ~τ λ µ= ⇒ = −0

2

3

( )

⋅∇∇+×∇×∇−∇−=

⋅∇+=

uupG

G

tD

uD

µµρ

σρρ

3

4

~

+

++−=

+=

k

k

ki

k

k

i

kk

i

k

ik

i

i

x

u

xx

u

x

u

xx

p

G

x

G

tD

uD

∂

∂

µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

ρ

∂

σ∂

ρρ

3

4

SOLO

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS (CONTINUE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-59-320.jpg)

![61

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.6.1.3) COMPUTATION

BUT

Φ

Φ = = +

= +

=

=

τ

∂

∂

τ

∂

∂

τ

∂

∂

τ

∂

∂

∂

∂

τ

τ τ

ik

i

k

ik

i

k

ki

k

i

ik

i

k

k

i

ik ik

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

u

x

D

ik ki1

2

1

2

τ µ λ δik ik kk ikD D= +2

HENCE ( )Φ = = +τ µ λ δik ik ik kk ik ikD D D D2

OR

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )

Φ = + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + + ⇒

=

2 2

2 2

11 11 22 33 11 22 11 22 33 22

33 11 22 33 33 12

2

21

2

13

2

31

2

23

2

32

2

µ λ µ λ

µ λ µ

D D D D D D D D D D

D D D D D D D D D D D

D Dij ji

( ) ( )Φ = + + + + + + + +2 2 2 211

2

22

2

33

2

12

2

13

2

23

2

11 22 33

2

µ λD D D D D D D D DOR

SOLO

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS (CONTINUE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-61-320.jpg)

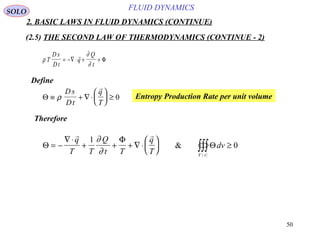

![62

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.6.1.3) COMPUTATION (CONTINUE)

USING STOKES ASSUMPTION: tr ~τ λ µ= ⇒ = −0

2

3

Φ

( ) ( )Φ = + + + + + + + +2 2 2 211

2

22

2

33

2

12

2

13

2

23

2

11 22 33

2

µ λD D D D D D D D D

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

Φ = + + − + + + + +

+ + + − + +

+ +

2

3

4

3

4

3

4

2

3

11 22 33

2

11 22 11 33 22 33 11

2

22

2

33

2

2

12

2

13

2

23

2

11 22 33

2

11

2

22

2

33

2

µ µ µ

µ

µ

λ

µ

D D D D D D D D D D D D

D D D D D D

D D D

OR

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )Φ = − + − + − + + + >

2

3

4 011 22

2

11 33

2

22 33

2

12

2

13

2

23

2µ

µD D D D D D D D D

SOLO

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS (CONTINUE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-62-320.jpg)

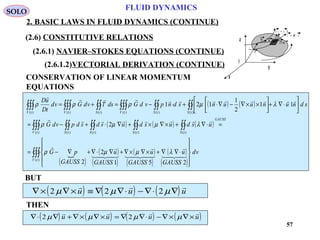

![63

FLUID DYNAMICS

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

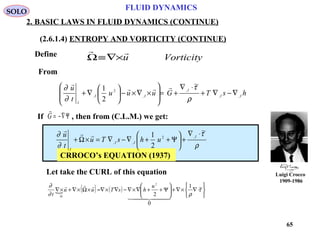

(2.6.1.4) ENTROPY AND VORTICITY

From (C.L.M.)

or

( ) ( )[ ]Du

Dt

u

t

u

u u G p u u

= + ∇

− × ∇ × = − ∇ − ∇ × ∇ × + ∇ + ∇ ⋅

∂

∂ ρ ρ

µ

ρ

λ µ

2

2

1 1 1

2

GIBBS EQUATION: T d s d h

d p

= −

ρ

∀

+⋅∇−

+⋅∇=

+⋅∇

→→→→

tld

pd

td

t

p

ldp

hd

td

t

h

ldh

sd

td

t

s

ldsT &

1

∂

∂

ρ∂

∂

∂

∂

Since this is true for d l t

→

&

T s h

p

T

s

t

h

t

p

t

∇ = ∇ −

∇

= −

ρ

∂

∂

∂

∂ ρ

∂

∂

&

1

SOLO

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.1) NAVIER–STOKES EQUATIONS (CONTINUE)

Josiah Willard Gibbs

(1903 – 1839)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-63-320.jpg)

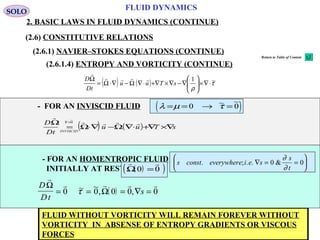

![68

FLUID DYNAMICS

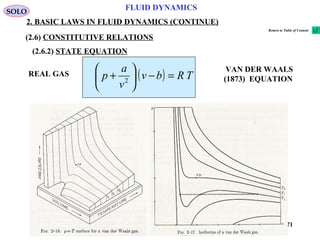

2. BASIC LAWS IN FLUID DYNAMICS (CONTINUE)

(2.6) CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONS

(2.6.2) STATE EQUATION

p - PRESSURE (FORCE / SURFACE)

V - VOLUME OF GAS

M - MASS OF GAS

R - 8314

- 286.9

T - GAS TEMPERATURE

- GAS DENSITY

[ ]m3

[ ]kg

[ ]J kg mol Ko

/ ( )⋅

[ ]J kg Ko

/ ( )⋅R

[ ]kgmol /−η

[ ]o

K

[ ]kg m/ 3

ρ

[ ]2

/ mN

IDEAL GAS

TRMVp η=

TMVp R=

DEFINE: ρ

ρ

= = =

∆ ∆M

V

v

V

M

&

1

pv T= R

p T= ρ R

OR

SOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-68-320.jpg)

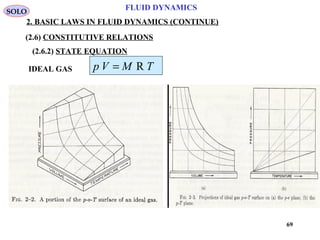

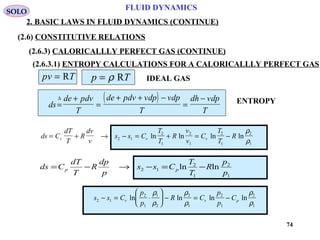

![82

SOLO

Dimensionless Equations

Constitutive Relations

TRp ρ=

2

2

1

uTCH p +=

Tkq ∇−=

TCh p=

−

== 2

00

2

00

2

00

1

U

TC

U

TC

C

R

U

p pp

p ρ

ρ

γ

γ

ρ

ρ

ρ

=

2

0

2

0 U

TC

U

h p

2

0

2

0

2

0 2

1

+

=

U

u

U

TC

U

H p

( )

∇

−= 2

0

0

00

0

000

0

3

00 U

TC

l

k

k

C

k

UlU

q p

p µρ

µ

ρ

( ) [ ]3

3

2~ Iuuu T

⋅∇−∇+∇= µµτ [ ]3

0

0

0000

0

0

0

0

0

0000

0

00 3

2~

I

U

u

l

UlU

u

l

U

u

l

UlU

T

⋅∇

−

∇+∇

=

µ

µ

ρ

µ

µ

µ

ρ

µ

ρ

τ

0/~ ρρρ = 0/

~

Uuu = gGG /

~

= ( )2

00/~ Upp ρ=

0/~ lUtt =

2

0/

~

UCTT p=( )2

00/~ Uρττ =

2

0/

~

UHH =

2

0/

~

Uhh =

2

0/~ Uee = ( )2

00/~ Uqq ρ= ( )2

/

~

UQQ =

∇=∇ 0

~

l

0/~ ρρρ = 0/

~

Uuu = gGG /

~

= ( )2

00/~ Upp ρ=

0/~ lUtt =

2

0/

~

UCTT p=( )2

00/~ Uρττ =

2

0/

~

UHH =

2

0/

~

Uhh =

2

0/~ Uee = ( )2

00/~ Uqq ρ= ( )2

/

~

UQQ =

∇=∇ 0

~

l

0/~ µµµ =

0/

~

kkk =

Dimensionless Variables are:

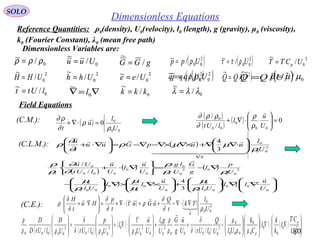

Reference Quantities: ρ0(density), U0(velocity), l0 (length), g (gravity), μ0 (viscosity),

k0 (Fourier Constant), λ0 (mean free path)

0/

~

λλλ =](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-82-320.jpg)

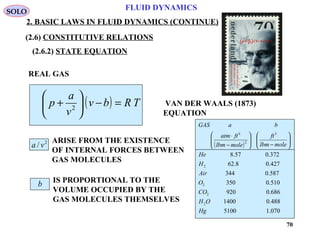

![83

SOLO

Dimensionless Equations

Dimensionless Constitutive Relations

2~

2

1~~

uTH +=

Tp

~~1~ ρ

γ

γ −

= Ideal Gas

( ) [ ]3

~~~

3

2~~~~~~~ Iu

R

uu

R e

T

e

⋅∇−∇+∇=

µµ

τ Navier-Stokes

Th

~~

= Calorically Perfect Gas

Tk

PR

q

re

~~~11~

∇−=

Fourier Law

Reynolds:

0

000

µ

ρ lU

Re =

Prandtl:

0

0

k

C

P

p

r

µ

=

0/~ ρρρ = 0/

~

Uuu = gGG /

~

= ( )2

00/~ Upp ρ=

0/~ lUtt =

2

0/

~

UCTT p=( )2

00/~ Uρττ =

2

0/

~

UHH =

2

0/

~

Uhh =

2

0/~ Uee = ( )2

00/~ Uqq ρ= ( )2

/

~

UQQ =

∇=∇ 0

~

l

0/~ ρρρ = 0/

~

Uuu = gGG /

~

= ( )2

00/~ Upp ρ=

0/~ lUtt =

2

0/

~

UCTT p=( )2

00/~ Uρττ =

2

0/

~

UHH =

2

0/

~

Uhh =

2

0/~ Uee = ( )2

00/~ Uqq ρ= ( )2

/

~

UQQ =

∇=∇ 0

~

l

0/~ µµµ =

0/

~

kkk =

Dimensionless Variables are:

Reference Quantities: ρ0(density), U0(velocity), l0 (length), g (gravity), μ0 (viscosity),

k0 (Fourier Constant), λ0 (mean free path)

0/

~

λλλ =

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-83-320.jpg)

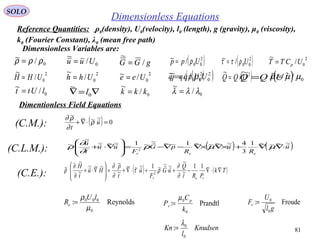

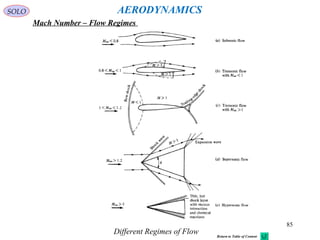

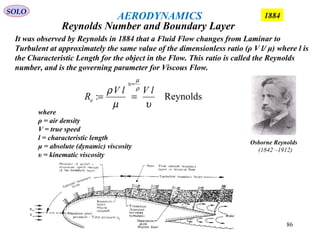

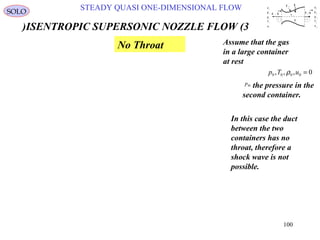

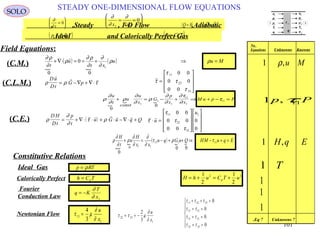

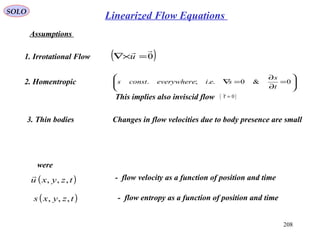

![84

SOLO

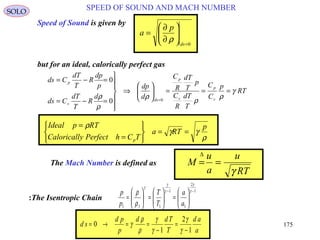

Mach Number

Mach number (M or Ma) / is a dimensionless quantity representing

the ratio of speed of an object moving through a fluid and the local

speed of sound.

• M is the Mach number,

• U0 is the velocity of the source relative to the medium, and

• a0 is the speed of sound

Mach:

0

0

a

U

M =

The Mach number is named after Austrian physicist and philosopher

Ernst Mach, a designation proposed by aeronautical engineer Jakob

Ackeret.

Ernst Mach

(1838–1916)

Jakob Ackeret

(1898–1981)

m

Tk

Mo

TR

a Bγγ

==0

• R is the Universal gas constant, (in SI, 8.314 47215 J K−1

mol−1

), [M1

L2

T−2

θ−1

'mol'−1

]

• γ is the rate of specific heat constants Cp/Cv and is dimensionless

γair = 1.4.

• T is the thermodynamic temperature [θ1

]

• Mo is the molar mass, [M1

'mol'−1

]

• m is the molecular mass, [M1

]

AERODYNAMICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-84-320.jpg)

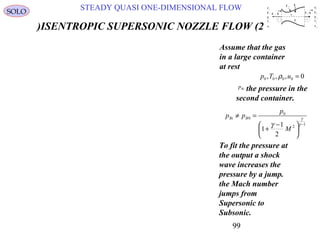

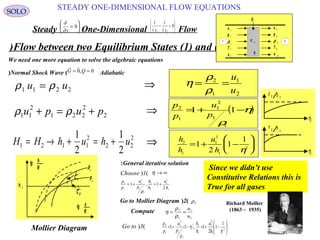

![102

SOLO

Steady One-Dimensional Flow

∂

∂ t

=

0

∂

∂

∂

∂x x2 3

0= =

Flow between two Equilibrium States (1) and (2)

u

p

ρ

T

e

u

p

ρ

T

e

τ 11

q

Q

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

1 2

τ µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

µ

∂

∂

δik

i

k

k

i

k

k

ik

u

x

u

x

u

x

= +

−

2

3

Assume Newtonian fluid (Navier-Stokes Eq.) in each state

( ) ( )

τ µ

∂

∂

τ τ µ

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

11

1

1

22 33

1

1

1

1 2

1

4

3

2

3

0

=

= =−

=−

⇐ =

⇔

u

x

u

x

q K

T

x

x

equilibrium

We obtain

Let integrate the field equations between state (1) and state (2)

[ ]ρu

1

2

0=

[ ]

ρ τ ρu p G dx2

1

2

12

1

2

1

1

2

0

+ − = ∫

[ ] ( )ρ τ ρuH q u G u Q dx1

2

11

1

2

1

1

2

0 0

+ −

= +∫

No. Equations Unknowns Knowns

ρ2 2,u ρ1 1,u1

1

1

p2

p G1 1,

H2 H1

3 4

STEADY ONE-DIMENSIONAL FLOW EQUATIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-102-320.jpg)

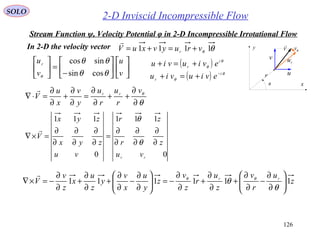

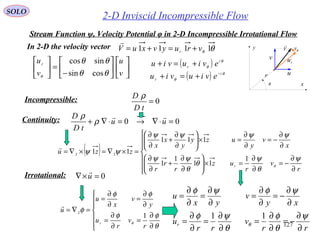

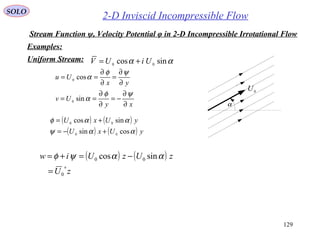

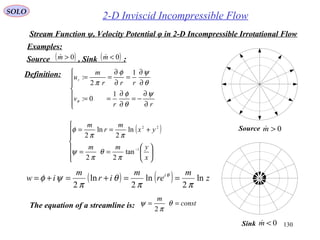

![128

2-D Inviscid Incompressible Flow

In 2-D the velocity vector

SOLO

Stream Function ψ, Velocity Potential φ in 2-D Incompressible Irrotational Flow

x

y V

u

v

ru

θv

r

θ

θθ 1111 vruyvxuV r

+=+=

−

=

v

u

v

ur

θθ

θθ

θ cossin

sincos ( ) θ

θ

i

r

eviuviu +=+

( ) θ

θ

i

r

eviuviu −

+=+

00 222

=∇⋅∇→∇=+=⋅∇ φφuu

2-D Incompressible:

2-D Irrotational:

( )

( ) ( ) ( )ψψψ

ψψ

222

0

222

222

1110

110

∇⋅∇−∇∇⋅=×∇×∇=

→×∇=×∇=+=×∇

zzz

zzuu

0

2

2

2

2

=∇=∇ ψφ

Complex Potential in 2-D Incompressible-Irrotational Flow:

( ) ( ) ( )

yixz

yxiyxzw

+=

+= ,,: ψφ

( ) =

zd

zwd

x

i

x ∂

∂

+

∂

∂ ψφ

yy

i

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

−

ψφ0=x

0=y

( )[ ] ( ) θ

θ

θ

θ

i

r

i

r

eviueviuVviu −∗∗

−=+==−

zd

wd

viu =− θ

θ

i

r e

zd

wd

viu =−

xyyx ∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

∂

∂

=

∂

∂ ψφψφ

Cauchy-Riemann Equations

We found:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-128-320.jpg)

![159

Kutta-Joukovsky

Nikolay Yegorovich Joukovsky

(1847-1921

( ) ( ) ( )cez

i

cez

R

cezUzw i

i

i

ˆln

2ˆ

ˆ

2

−

Γ

+

−

+−= −

−

−

∞

α

α

α

π

( )

viu

cez

i

cez

R

Ue

zd

wd

ii

i

−=

−

Γ

+

−

−= −−∞

−

ˆ

1

2ˆ

1 2

2

αα

α

π

we have

Kutta Condition: The Flow Leaves Smoothly from the Trailing Edge.

This is an Empirical Observation that results from the tendency of

Viscous Boundary Layer to Separate at Trailing Edge.

Martin Wilhelm Kutta

(1867 – 1944)

( )

( )

( ) yx

i

ii

i

az

az

caBcaA

BiA

i

BiA

R

Ue

cea

i

cea

R

Ue

zd

wd

ivu

+=−=

−

Γ

+

−

−=

−

Γ

+

−

−===−

∞

−

−−∞

−

=

=

αα

π

π

α

αα

α

sin:,cos:

1

2

1

ˆ

1

2ˆ

10

2

2

2

2

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

( )

+

Γ

++−+

Γ

+−−−+

=

∞∞

−

222

22222222222

2

2

2

BA

BAAURBAiBABBARBAU

e i ππα

Profile Theory Using Conformal Mapping

AERODYNAMICSSOLO

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-159-320.jpg)

![160

we have

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

( )

+

Γ

++−+

Γ

+−−−+

==

∞∞

−

=

222

22222222222

2

2

2

0

BA

BAAURBAiBABBARBAU

e

zd

wd i

az

ππα

( ) βααβαα sinsinsin:,coscoscos: RacaBRaacaA yx +=+=−−=−=

( ) ( )

( ) ( )[ ] 222

2222

coscos2cos12

sinsincoscos

RRaRa

RaaRaBA

≈−−++−=

++−+=+

ββαα

βαβα

( ) π2

20 222 Γ

++−= ∞ BAAURBA ( )βαπππ sinsin444 22

2

RaUUBUB

BA

R

+=≈

+

=Γ ∞∞∞

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( )[ ] ( )( ) 0

2

2

22222222222

2222222222222222

≈−++=+−+=

−−−+=

Γ

+−−−+

∞∞

∞∞∞

RBABAUBARBAU

URBBARBAUBABBARBAU

π

Let check

For this value of Γ, we have

This value of Γ satisfies the Kutta Condition

0=

=az

zd

wd

Joukovsky Airfoils

Profile Theory Using Conformal Mapping

AERODYNAMICSSOLO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-160-320.jpg)

![192

NORMAL SHOCK WAVESSOLO

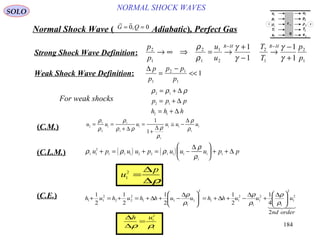

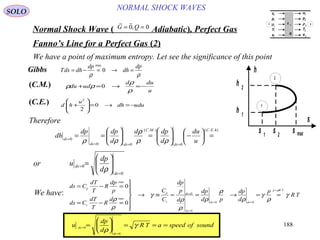

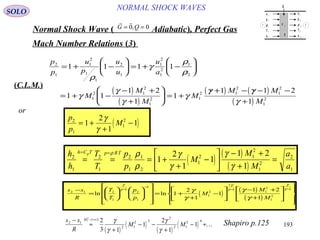

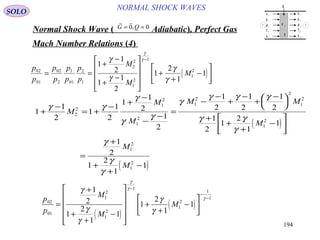

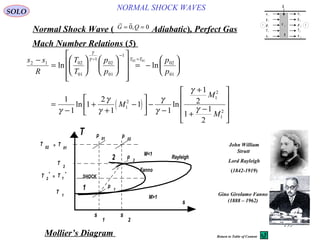

Normal Shock Wave ) Adiabatic(, Perfect Gas

G Q= =0 0,

Mach Number Relations )2(

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )( ) ( )

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

2

1

1

2

1 1

2

1

1

1 2

1

2 1 2

1 1 1 1 1

1

2

=

+

− −

=

+ − −

=

+

+

− +

− −

=

− +

+ / + − / / + − / + − −

∗

=

∗

∗

∗

γ

γ γ γ

γ

γ

γ

γ

γ

γ γ γ γ γ

or

( )

M

M

M

M

M

H H

A A

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

21 2

1 2

1

1

2

1

2

2

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

=

+

−

−

−

=

+

+

−

+

+

−

=

=

γ

γ

γ γ

γ

γ

γ

( )

( )

ρ

ρ

γ

γ

2

1

1

2

1

2

1 2

1

2

2 1

2 1

2

1

2

1 2 1

1 2

= = = = =

+

− +

=

∗

∗

A A u

u

u

u u

u

a

M

M

M

u

p

ρ

T

e

u

p

ρ

T

e

τ 11

q

Q

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

1 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-192-320.jpg)

![197

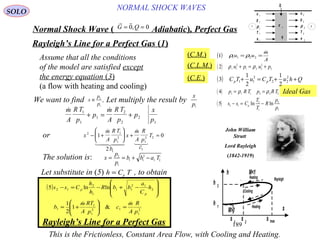

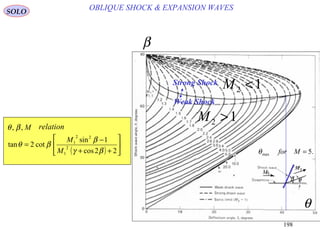

OBLIQUE SHOCK & EXPANSION WAVESSOLO

For a calorically Perfect Gas

( )

( )

( )

( )[ ]

( )[ ]

2

1

1

2

1

2

2

1

2

12

2

2

1

1

2

2

1

2

1

1

2

11/2

1/2

1

1

2

1

21

1

ρ

ρ

γγ

γ

γ

γ

γ

γ

ρ

ρ

p

p

T

T

M

M

M

M

p

p

M

M

n

n

n

n

n

n

=

−−

−+

=

−

+

+=

+−

+

=

βsin11 MMn =

( )θβ −

=

sin

2

2

nM

M

Now we can compute

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

⋅+

−

=

−

+

−+

===

−

⇒

=

=−

=

θββ

θβ

β

θβ

βγ

βγ

ρ

ρ

β

θβ

θβ

β

tantan1tan

tantan

tan

tan

sin1

sin12

tan

tan

tan

tan

22

1

22

1

2

1

1

2

12

2

2

1

1

M

M

u

u

ww

w

u

w

u](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-197-320.jpg)

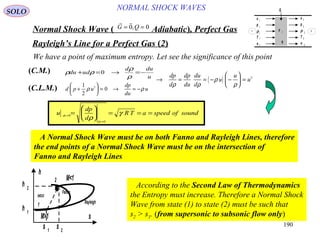

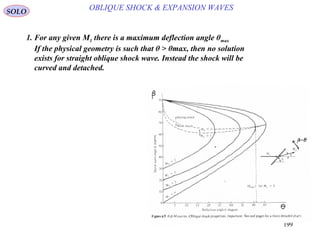

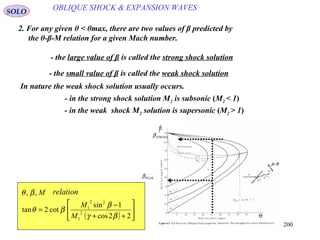

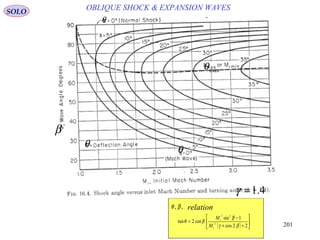

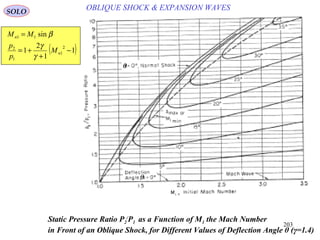

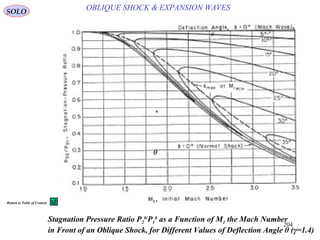

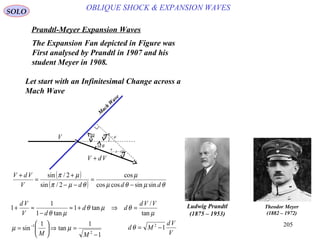

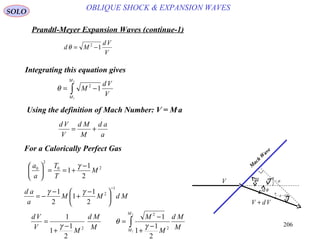

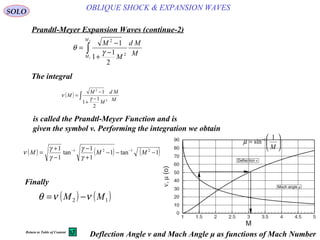

![202

( )[ ]

( )[ ]

( )θβ

γγ

γ

β

−

=

−−

−+

=

=

sin

11/2

1/2

sin

2

2

2

1

2

12

2

11

n

n

n

n

n

M

M

M

M

M

MM

SOLO

θ

maxθ

OBLIQUE SHOCK & EXPANSION WAVES

Mach Number in Back of Oblique Shock M2 as a Function of the Mach Number

in Front of the Shock M , for Different Values of Deflection Angle θ (γ=1.4)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-202-320.jpg)

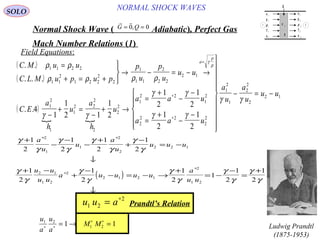

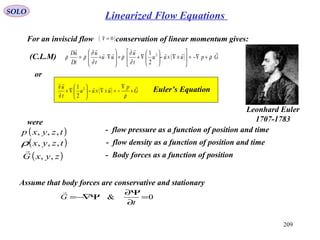

![211

SOLO

For an isentropic ideal gas we have

2

2

11 a

ad

T

Tdd

p

pd

−

=

−

==

γ

γ

γ

γ

ρ

ρ

γ

where

ρ

γ

γ

ρρ

p

TR

d

pdp

a

s

===

∂

∂

=2

is the square of the speed of sound

In this case

2

2

2

1

1

1 2

ad

a

adppd

RTa

RTp

−

=

−

=

=

=

γργ

γ

ρ γ

ρ

and

[ ]222

1

1

1

1

2

2

∞−

−

=

−

= ∫∫

∞∞

aaad

pd

a

a

p

p

γγρ

Using the Bernoulli’s Equation we obtain

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

Ψ−Ψ+−+

∂

Φ∂

−−=−=− ∞∞∞ ∫

∞

2222

2

1

11 Uu

t

dp

aa

p

p

γ

ρ

γ

( )

2

1

2

2

1

2

2

1

2

1

0

Ψ+++

∂

Φ∂

=

Ψ∇++

+Φ

∂

∂

= ∫∫

∞

p

p

pd

u

t

pd

udd

t ρρ

Bernoulli’s Equation

for Irrotational

and Inviscid Flow

Linearized Flow Equations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-211-320.jpg)

![212

SOLO

Let use the conservation of mass (C.M.) equation

(C.M.) 0=⋅∇+ u

tD

D

ρ

ρ

or

tD

D

u

ρ

ρ

1

−=⋅∇

Let go back to Bernoulli’s Equation ( ) ( )

Ψ−Ψ+−+

∂

Φ∂

−= ∞∞∫

∞

22

2

1

Uu

t

pd

p

p

ρ

and use the Leibnitz rule of differentiation: ( ) ( )uxFdxuxF

xd

d

x

x

,,

0

=∫

to obtain

ρρ

1

=∫

∞

p

p

pd

pd

d

Now we can compute tD

Da

tD

D

d

pd

tD

pD

tD

pDpd

pd

dpd

tD

D

p

p

p

p

ρ

ρ

ρ

ρρρρρ

2

11

===

= ∫∫

∞∞

Therefore ( ) ( )

Ψ−Ψ+−+

∂

Φ∂

=−=−=⋅∇ ∞∞∫

∞

22

22

2

1111

Uu

ttD

D

a

pd

tD

D

atD

D

u

p

p

ρ

ρ

ρ

Since ( )[ ] 0=Ψ−Ψ= ∞∞

tD

D

u

tD

D

we have

∇⋅+

∂

∂

⋅+

∂

Φ∂

=

∇⋅+

∂

Φ∂

∇⋅+

∂

∂

⋅+

∂

Φ∂

=

=

+

∂

Φ∂

∇⋅+

∂

∂

=

+

∂

Φ∂

=⋅∇

Φ∇=

2

2

1

2

1

2

11

2

11

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

u

u

t

u

u

ta

u

u

t

u

t

u

u

ta

u

t

u

ta

u

ttD

D

a

u

u

GOTTFRIED WILHELM

von LEIBNIZ

1646-1716

Linearized Flow Equations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-212-320.jpg)

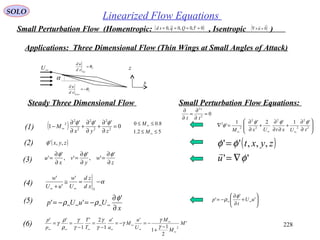

![224

Linearized Flow EquationsSOLO

Boundary Conditions (continue -1)

1. Flow must be parallel at the Wing Surface.

The Wing Surface S is defined by

zU (x,y) – Upper Surface

zL (x,y) – Lower Surface

Since the Small Perturbation gives

Linear Equation we can divide the

Airfoil in the Camber Distribution zC (x,y)

and the Thickness Distribution zt (x,y) by:

( )

( )

( ) Sonyxallfor

x

z

Uyxw

x

z

Uyxw

C

C

t

t

,

0,,'

0,,'

−

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

±=±

∞

∞

α

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

−=

+=

⇔

−=

+=

2/,,,

2/,,,

,,,

,,,

yxzyxzyxz

yxzyxzyxz

yxzyxzyxz

yxzyxzyxz

LUt

LUC

tCL

tCU

Because of the Linearity the complete solution can be obtained by summing the

Solutions for the following Boundary Conditions

Superposition of

• Angle of Attack

•Camber Distribution

•Thickness Distribution

Section AA

(enlarged)

Wake region

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) Sonyxallfor

x

z

x

z

Uyxwyxwyxw

x

z

x

z

Uyxwyxwyxw

tC

tCL

tC

tCU

,

0,,'0,,'0,,'

0,,'0,,'0,,'

∂

∂

−−

∂

∂

=−+=±

∂

∂

+−

∂

∂

=++=±

∞

∞

α

α](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-224-320.jpg)

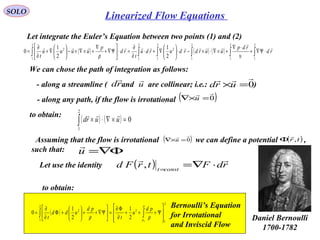

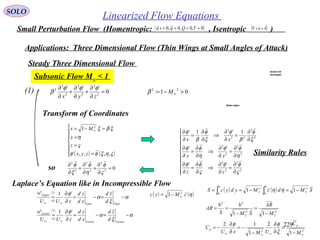

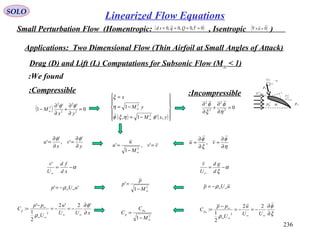

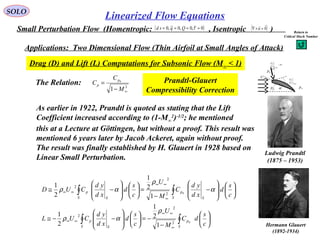

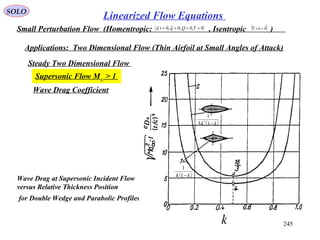

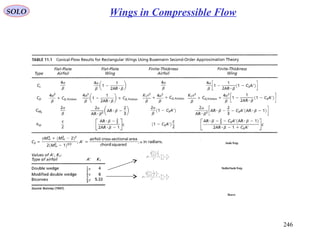

![SOLO

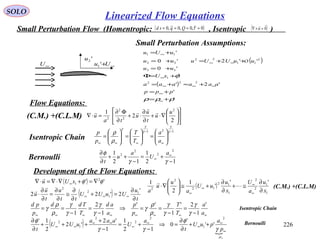

Small Perturbation Flow (Homentropic: , Isentropic )( )0~,0,0~,0 ==== τQqsd ( )0

=×∇ u

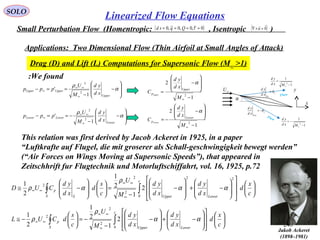

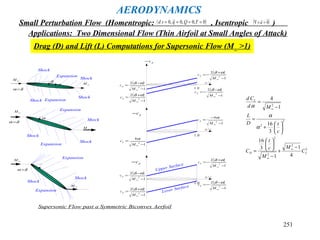

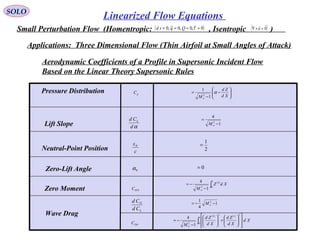

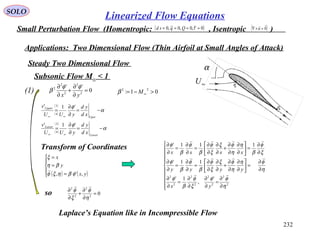

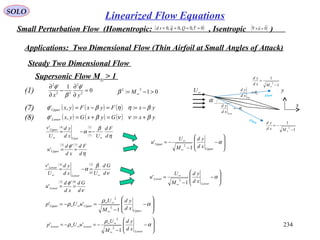

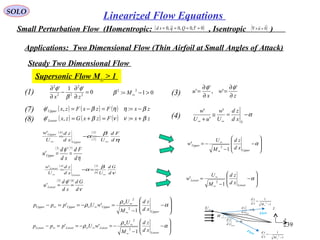

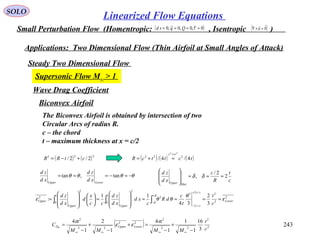

Applications: Two Dimensional Flow (Thin Airfoil at Small Angles of Attack)

Several improved formulas where developed:

( )[ ] 2/11/1 0

0

222

p

p

p

CMMM

C

C

∞∞∞ −++−

= Karman-Tsien

Rule

Linearized Flow Equations

( ) 0

0

2222

12/

2

1

11 p

p

p

CMMMM

C

C

−

−

++−

=

∞∞∞∞

γ

Laitone’s

Rule

Comparison of several compressibility corrections

compared with experimental results for NACA 4412

Airfoil at an angle of attack of α = 1◦

.

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-238-320.jpg)

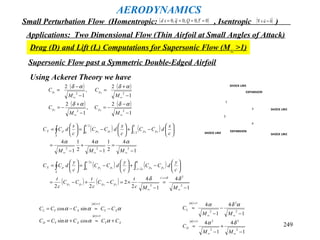

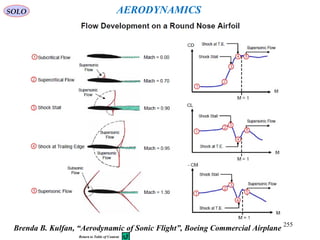

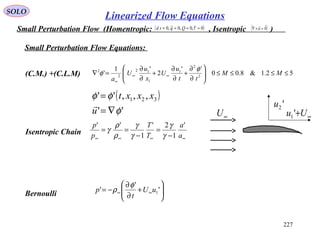

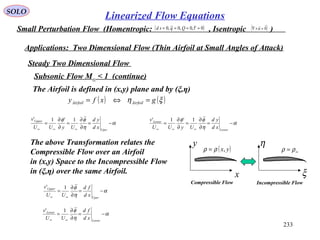

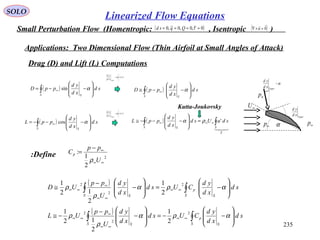

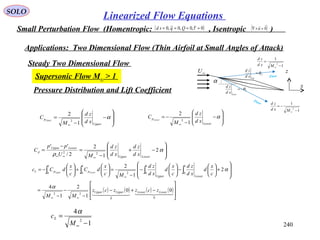

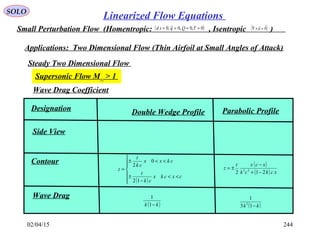

![247

SOLO

Linearized Flow Equations

Small Perturbation Flow (Homentropic: , Isentropic )( )0~,0,0~,0 ==== τQqsd ( )0

=×∇ u

Applications: Two Dimensional Flow (Thin Airfoil at Small Angles of Attack)

Steady Two Dimensional Flow

Supersonic Flow M∞ > 1

Pitching Moment Coefficient

The Pitching Moment Coefficient about the

Leading Edge for any Thin Airfoil is given by

xdx

xd

zd

xd

zd

Mcc

x

d

c

x

C

c

x

d

c

x

Cc

c

LowerUpper

ppM LowerUpperLE ∫∫∫

−+

−

−

−=

+

−=−

∞

022

1

0

1

0

1

2

αα

Thus

+

−

+

−

−= ∫∫

∞∞

xdzxdz

McM

c

c

Lower

c

UpperM LE 00222

1

2

1

2α

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] xdzxdzczczcxdzzxxdzzxxdx

xd

zd

xd

zd c

Lower

c

UpperLowerUpper

c

Lower

cx

xLower

c

Upper

cx

xUpper

c

LowerUpper

∫∫∫∫∫ −−−=−+−=

+

=

=

=

= 00

0

00000

Using integration by parts

Symmetric Airfoil zUpper = -zLower

1

2

2

−

−=

∞M

cM

α

The distance of the Airfoil Center of Pressure aft of the Leading Edge is given by

cc

M

M

c

c

c

c

x

L

MN

2

1

1/4

1/2

2

2

=⋅

−

−

=⋅−=

∞

∞

α

α

α

L

∞U

x

Return to Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fluiddynamics-141022060736-conversion-gate02/85/Fluid-dynamics-247-320.jpg)