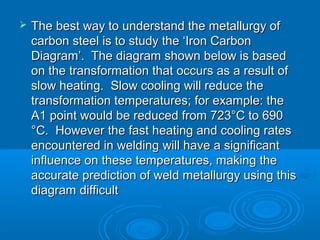

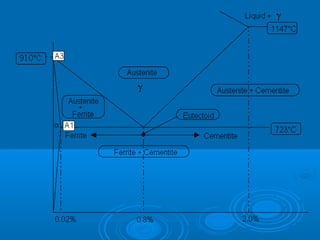

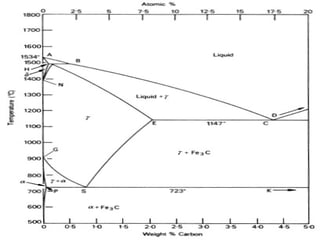

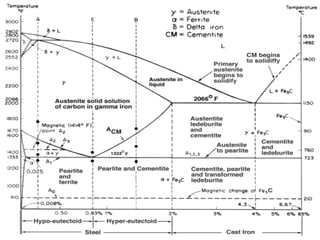

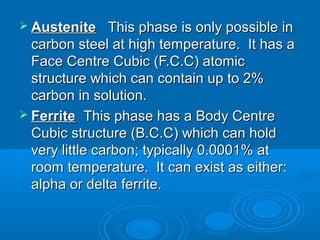

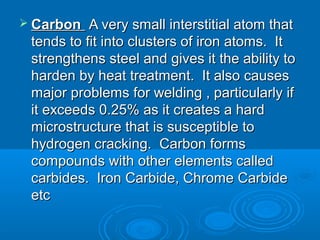

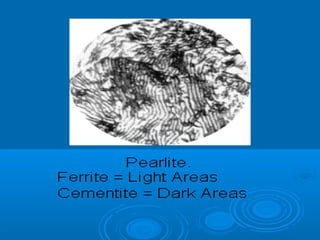

The document discusses the iron-carbon phase diagram, which shows the different crystal structures that iron takes on at various temperatures depending on the amount of carbon present. It defines various phases including austenite, ferrite, cementite, pearlite, and martensite, and explains how heating and cooling rates affect the microstructure. Heat treatments like tempering, annealing, and normalizing are also summarized in terms of their effects on the steel microstructure.