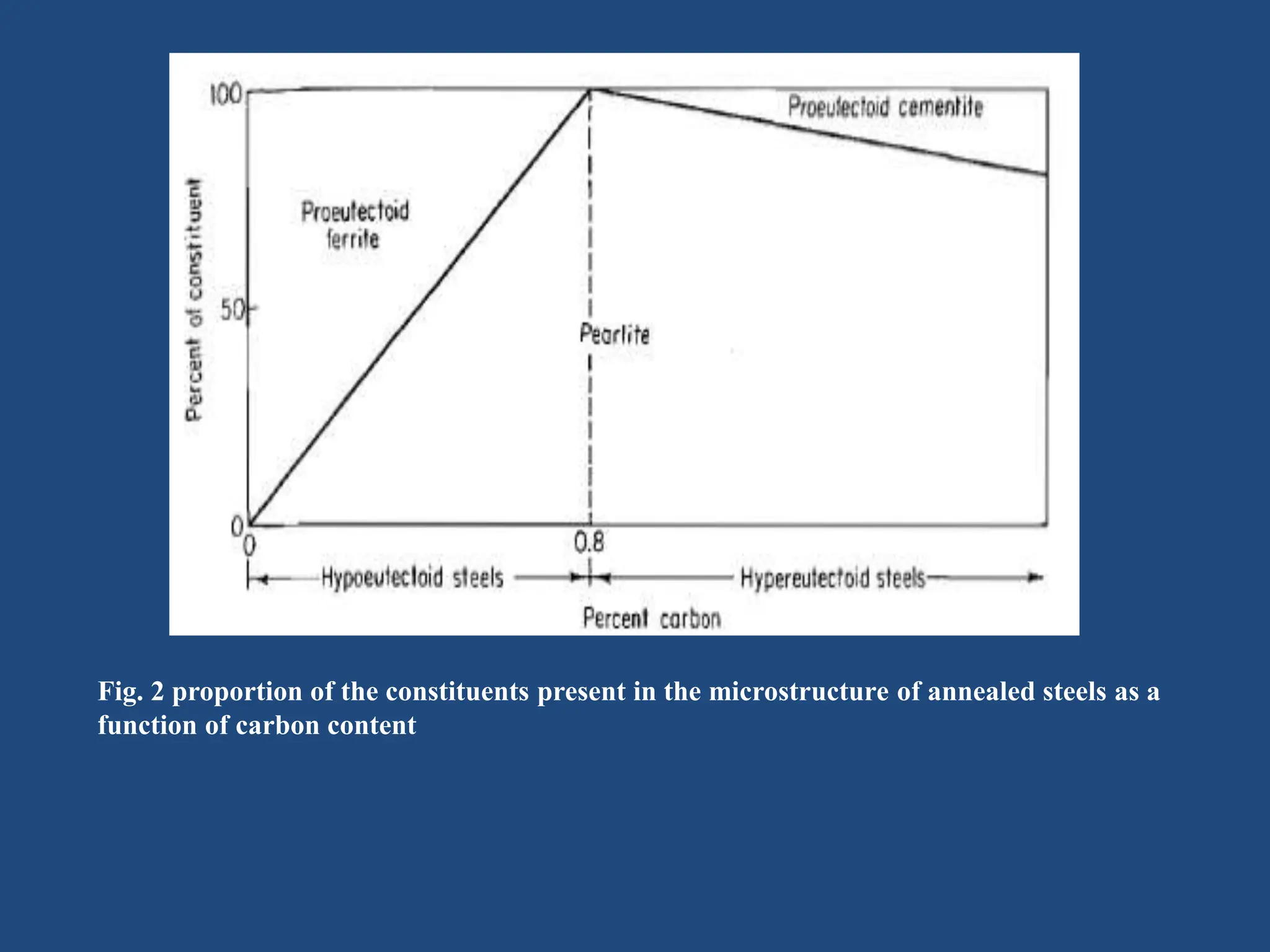

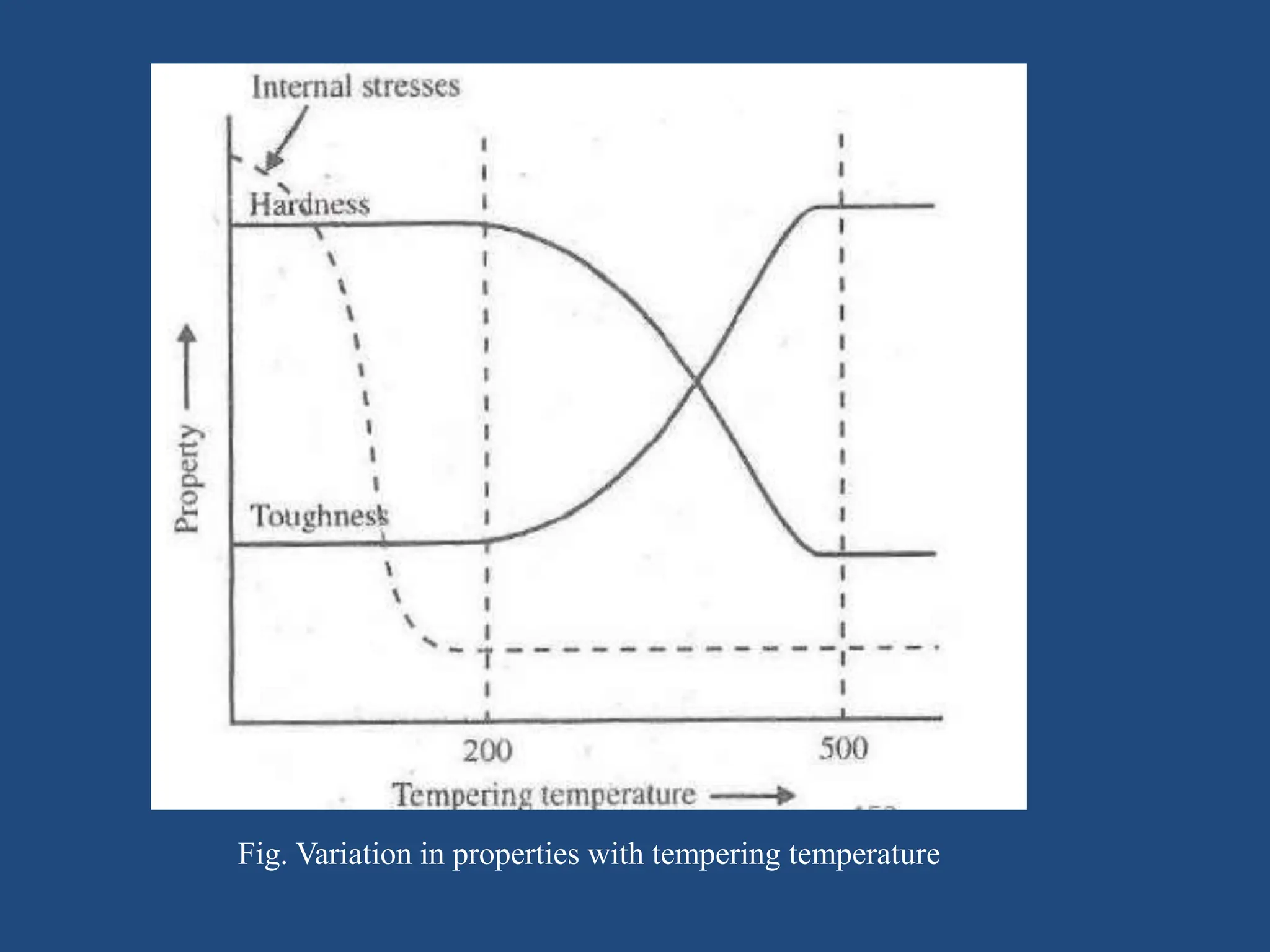

The document provides an in-depth overview of heat treatment processes for steels, including annealing, normalizing, and hardening, each detailing their methods, purposes, and effects on steel's physical and mechanical properties. It explains how these processes, such as tempering, alleviate brittleness and internal stresses in hardened steels, and discusses the stages and temperatures involved in tempering. Overall, the text emphasizes the criticality of proper heat treatment methods to achieve desired material characteristics essential for engineering applications.