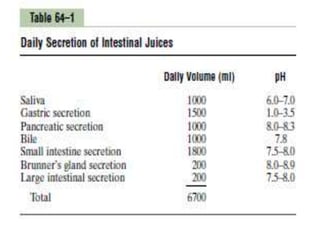

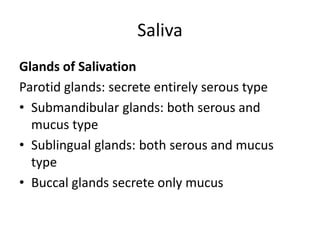

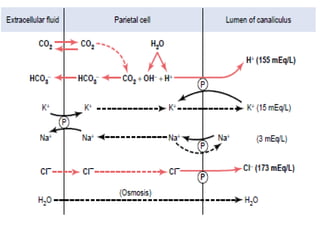

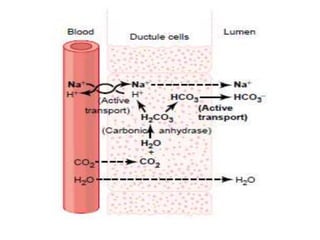

This document summarizes the secretions of the gastrointestinal tract. It describes the salivary glands and their secretions including serous and mucus types. It then discusses the stomach secretions including hydrochloric acid from parietal cells and pepsinogen from chief cells. The pancreas secretes bicarbonate and digestive enzymes including trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen to digest proteins, carbohydrates, and fats in the small intestine. Regulation and functions of these secretions are also covered.