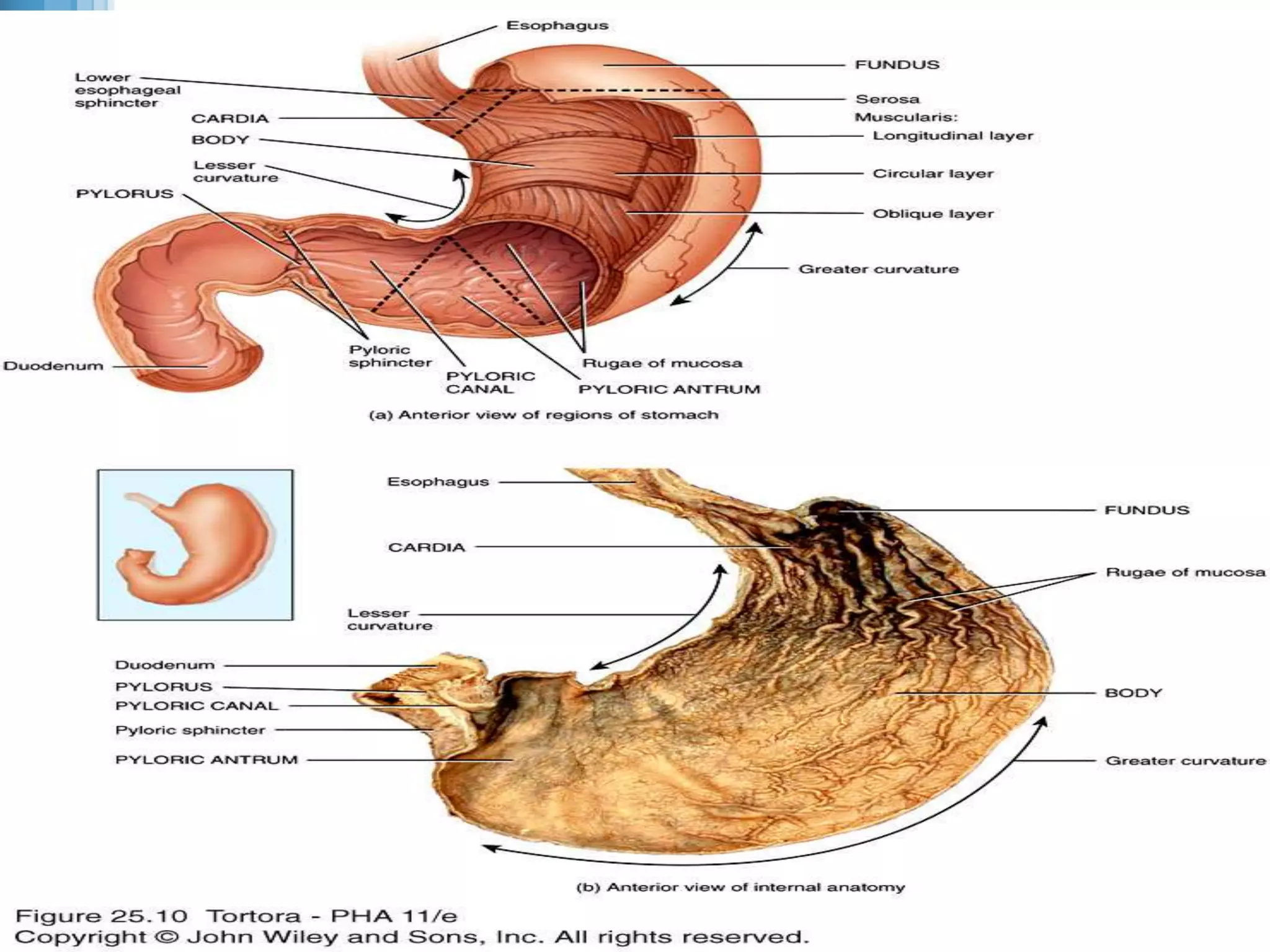

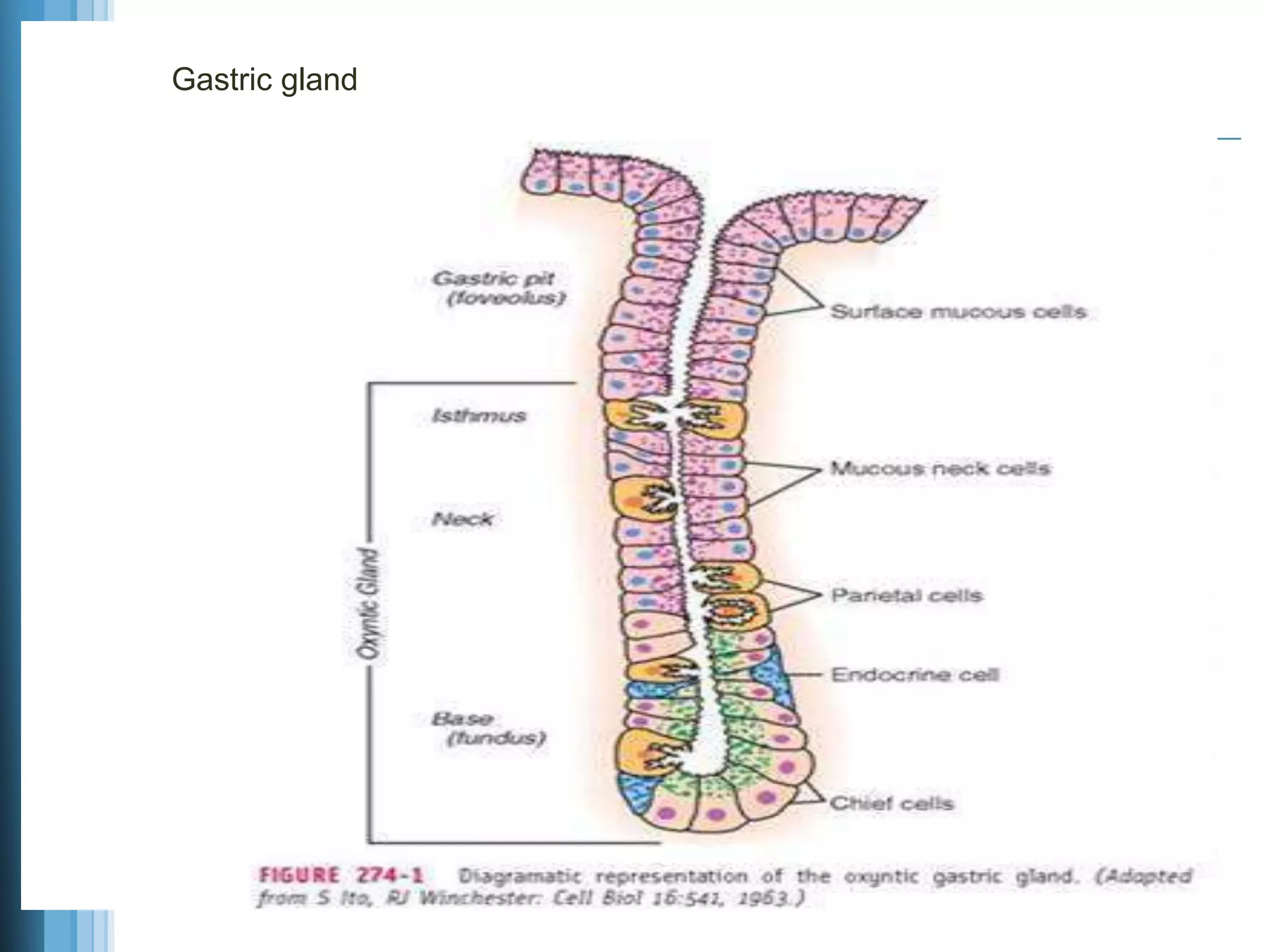

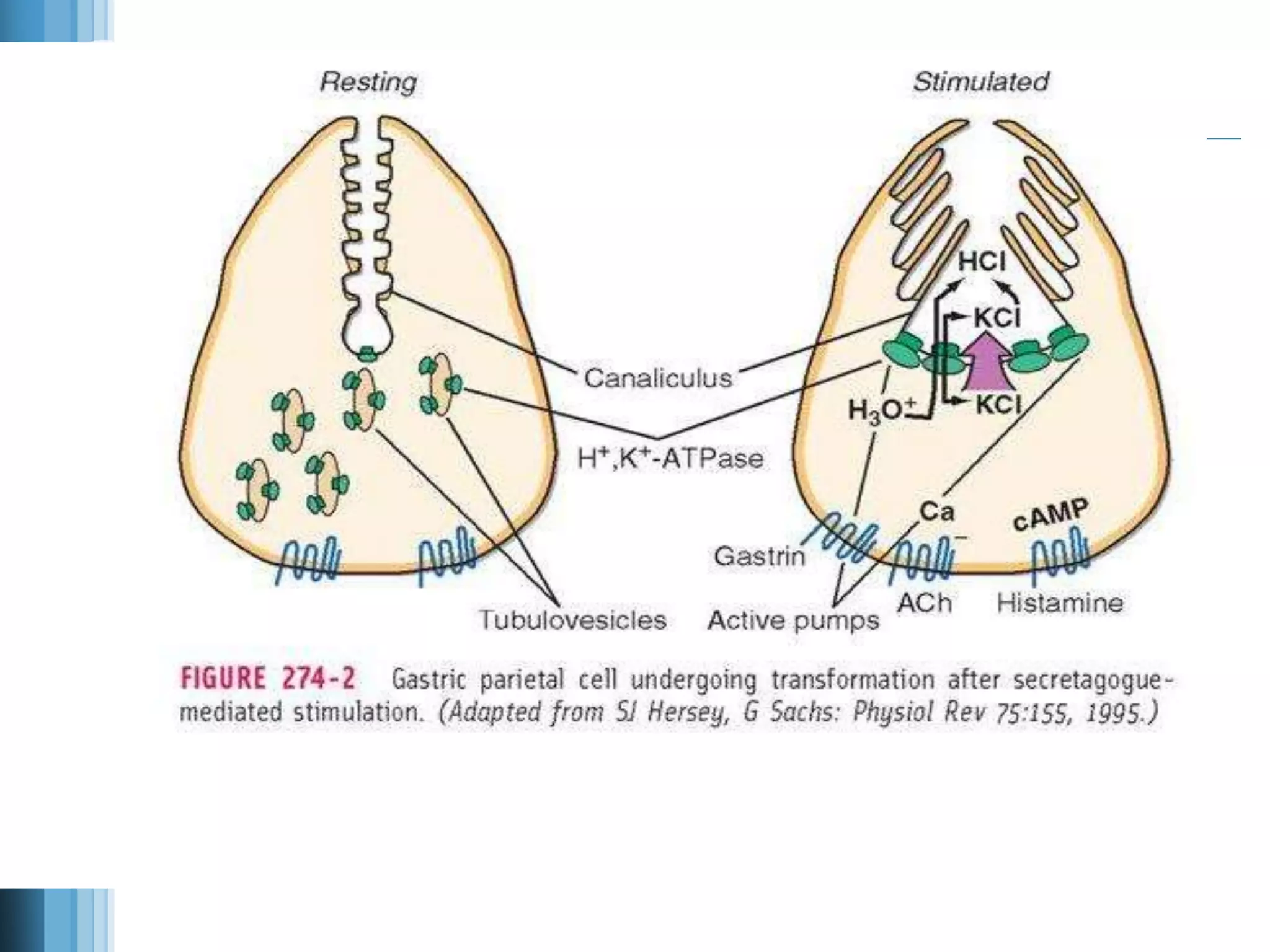

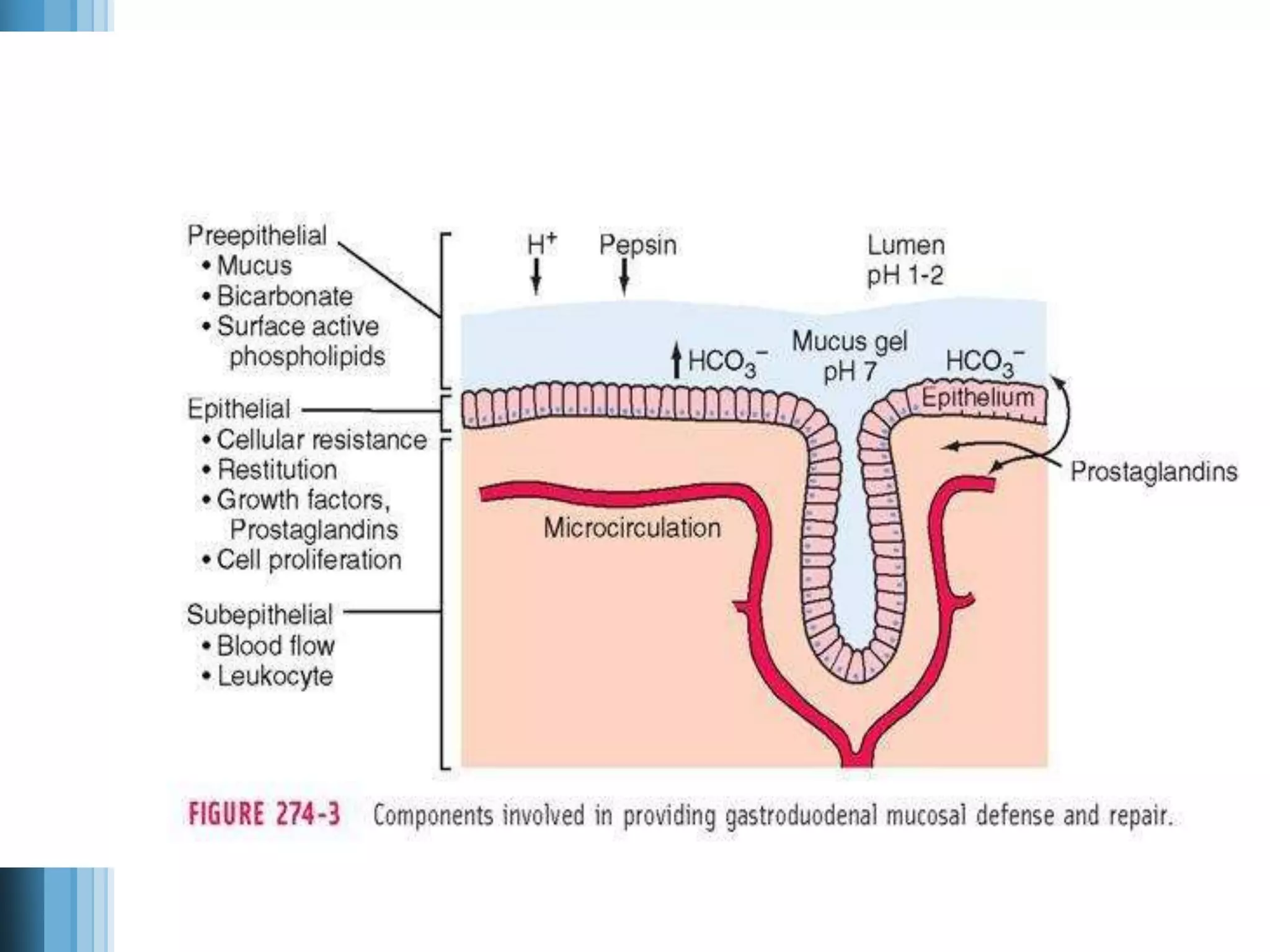

The document discusses the anatomy, histology, and physiology of the stomach. It describes the three layers of the stomach wall - the submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. It details the three types of gastric glands - mucous, parietal, and chief cells - and their secretions. Parietal cells secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor. Chief cells secrete pepsinogen and gastric lipase. The stomach's defenses against acid are also summarized, including the mucus barrier and bicarbonate secretion.