This document provides information about epigenetics. It discusses:

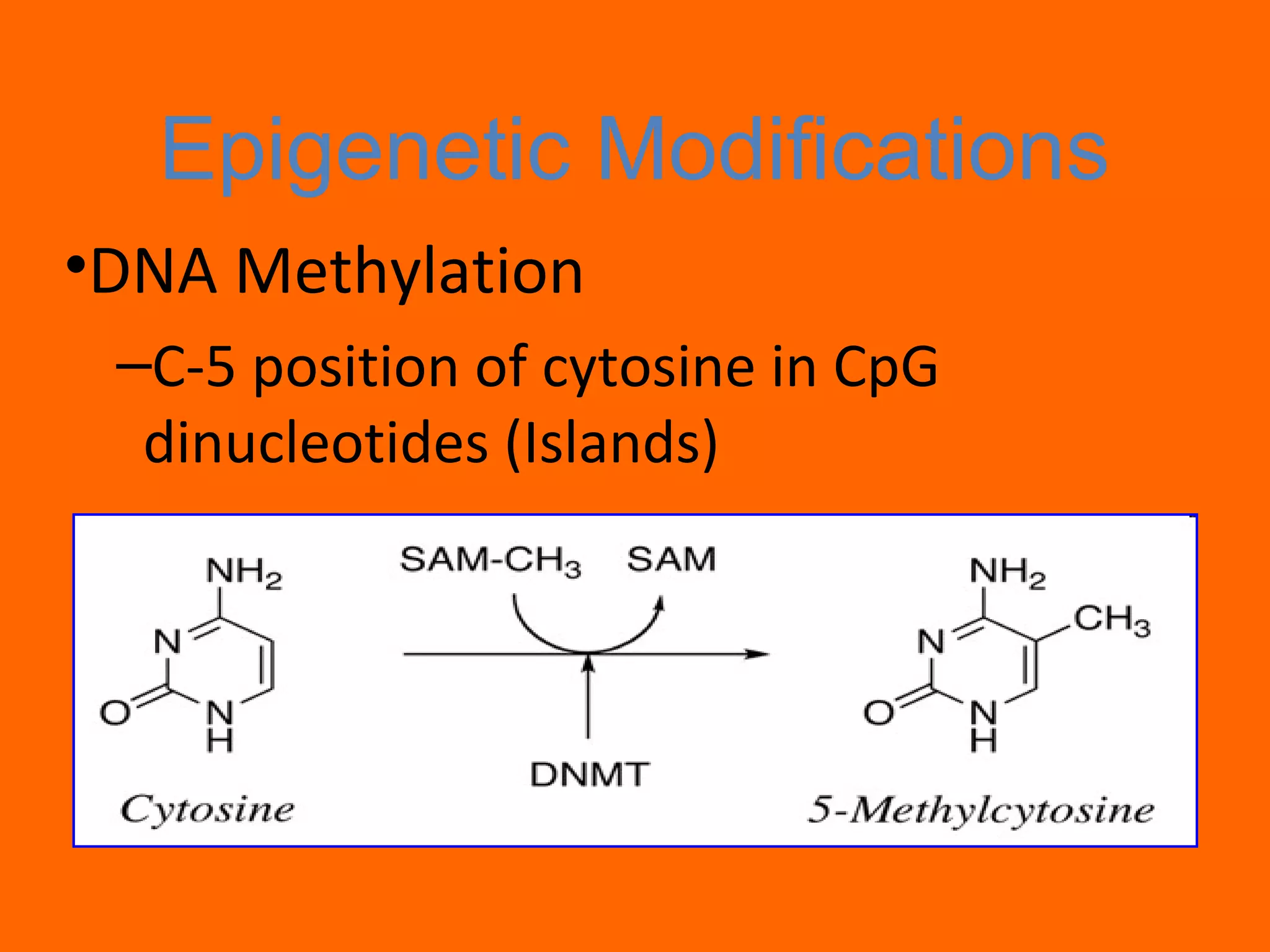

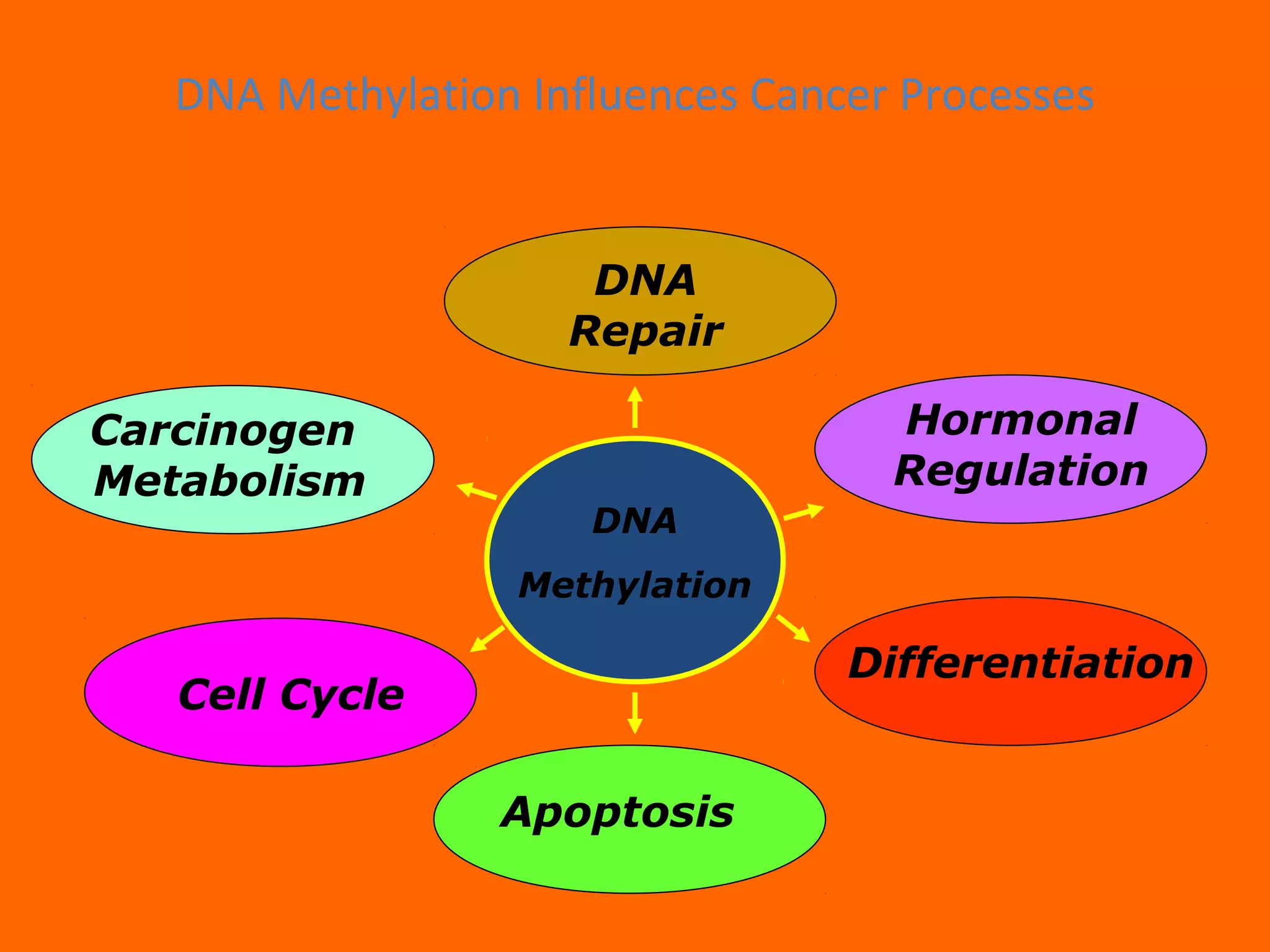

1. What epigenetics is and some key epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation and histone modifications.

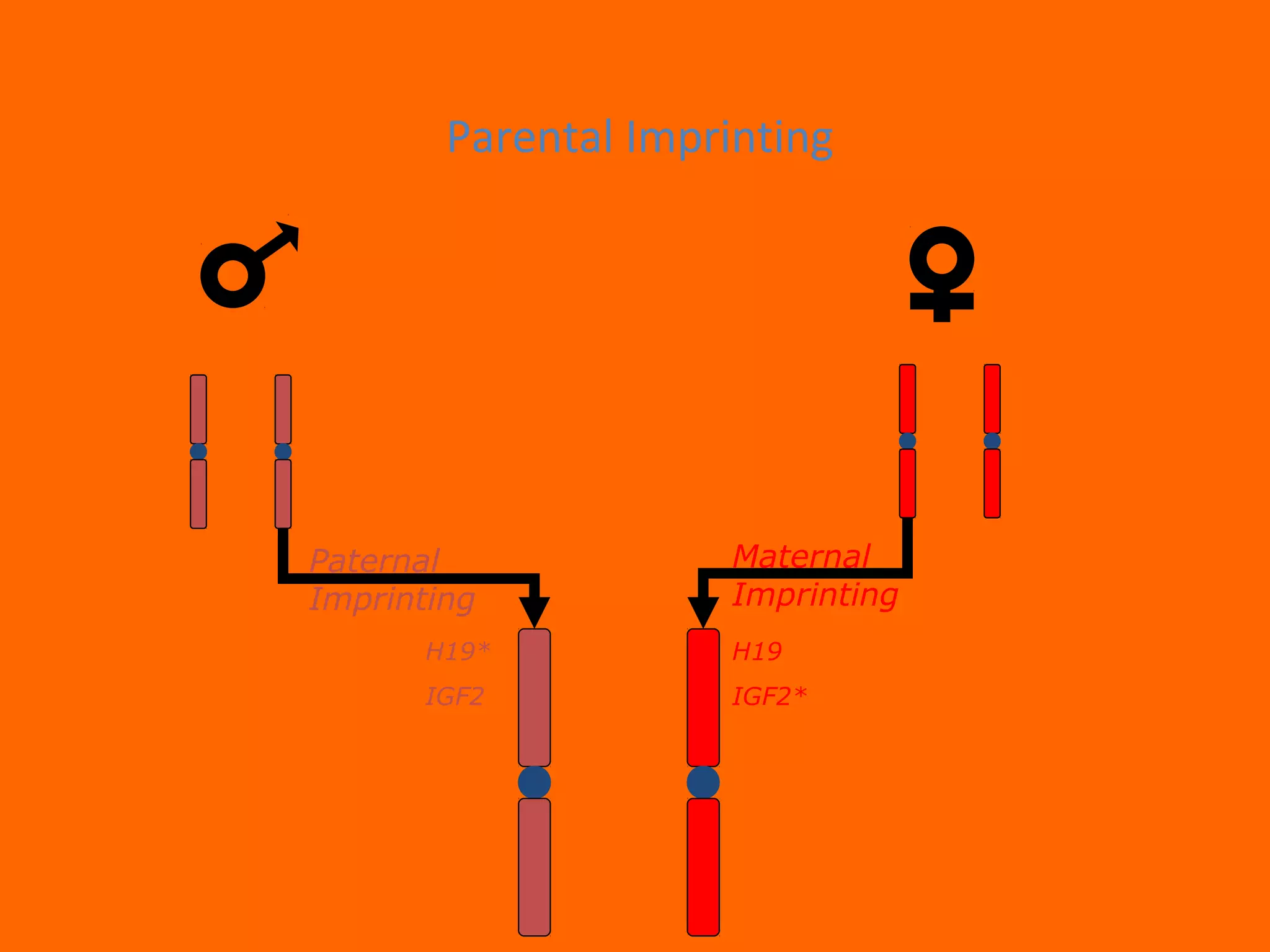

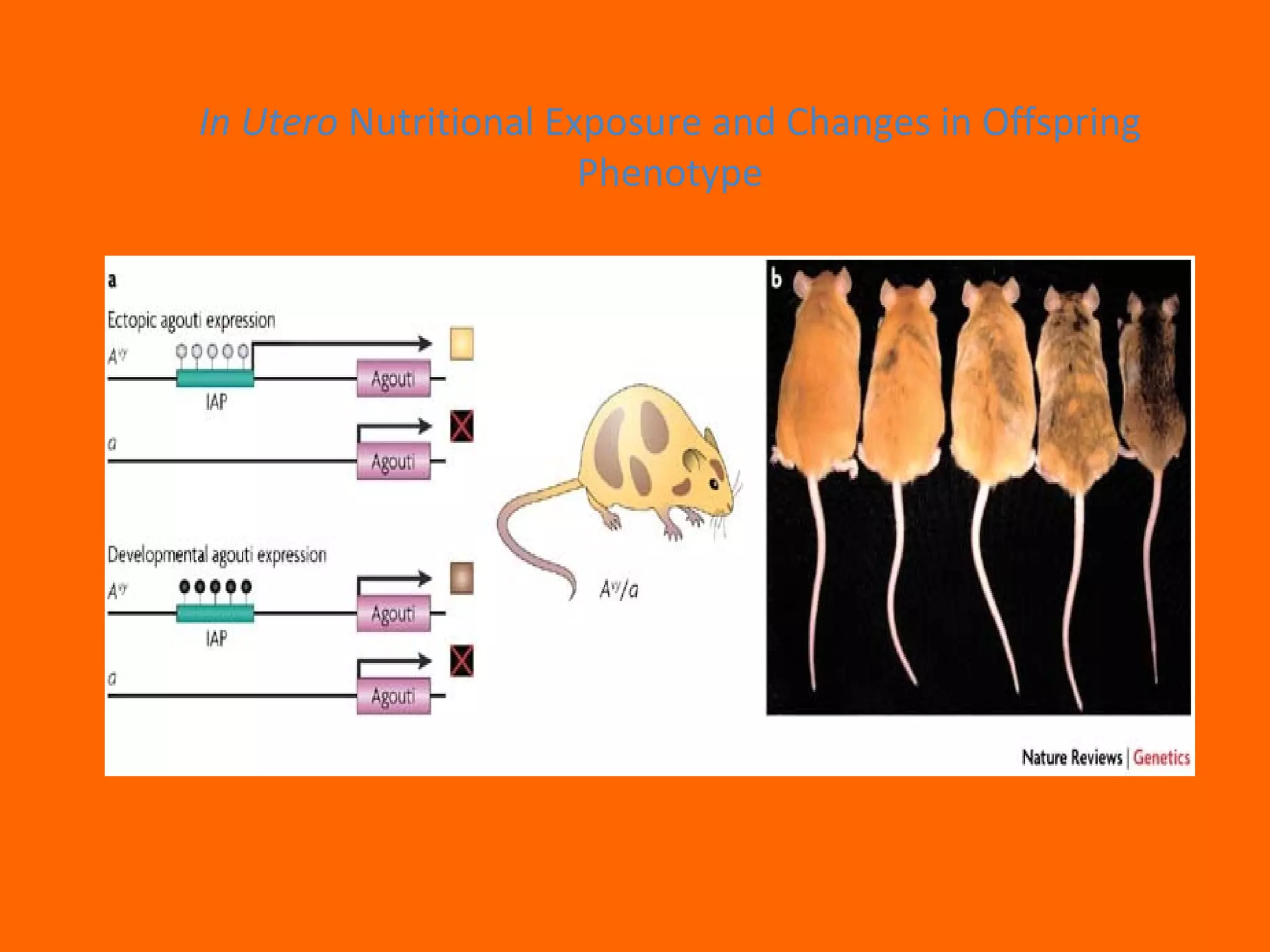

2. Examples of epigenetically regulated phenomena like cellular differentiation, X-chromosome inactivation, and imprinting.

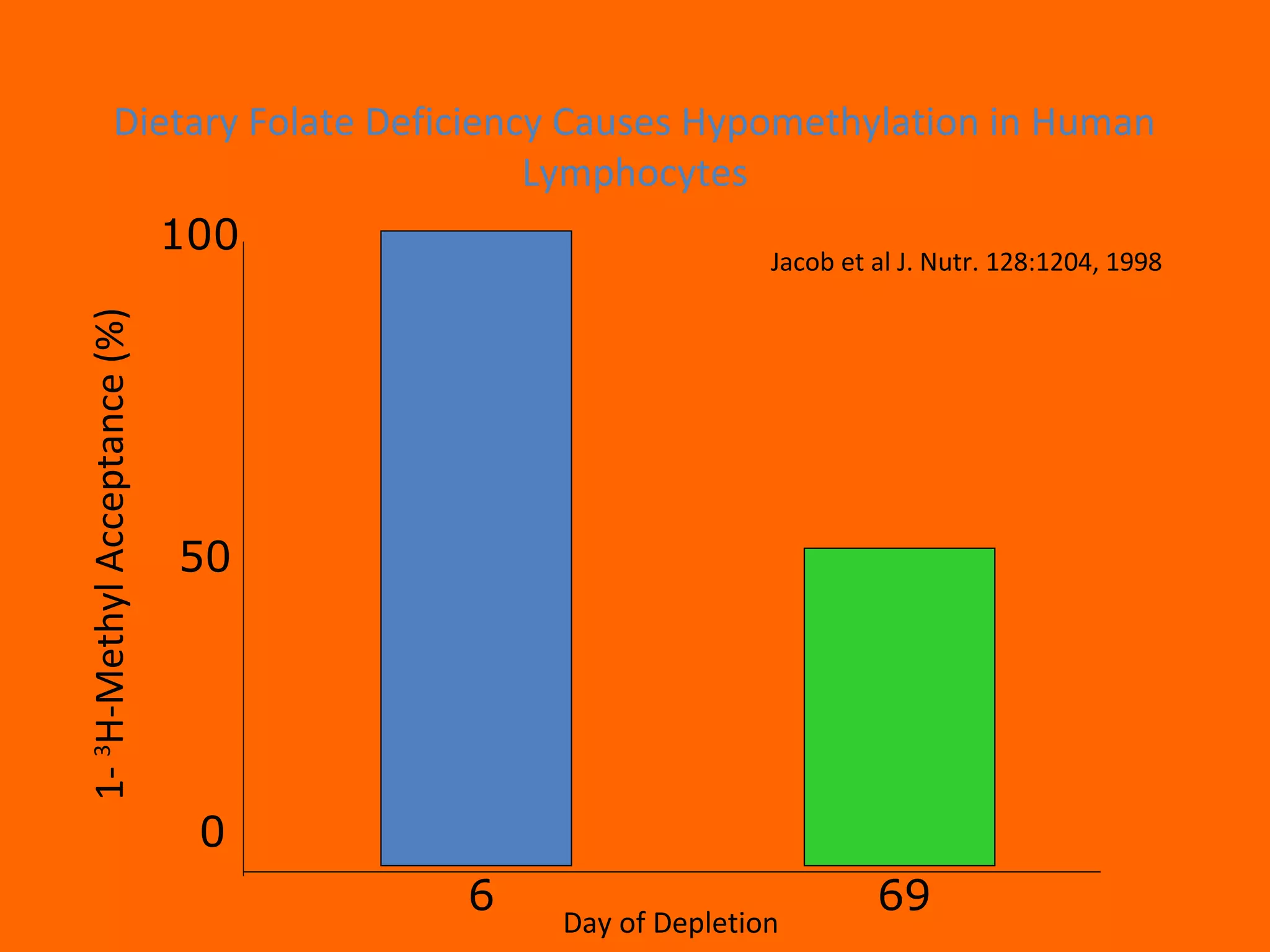

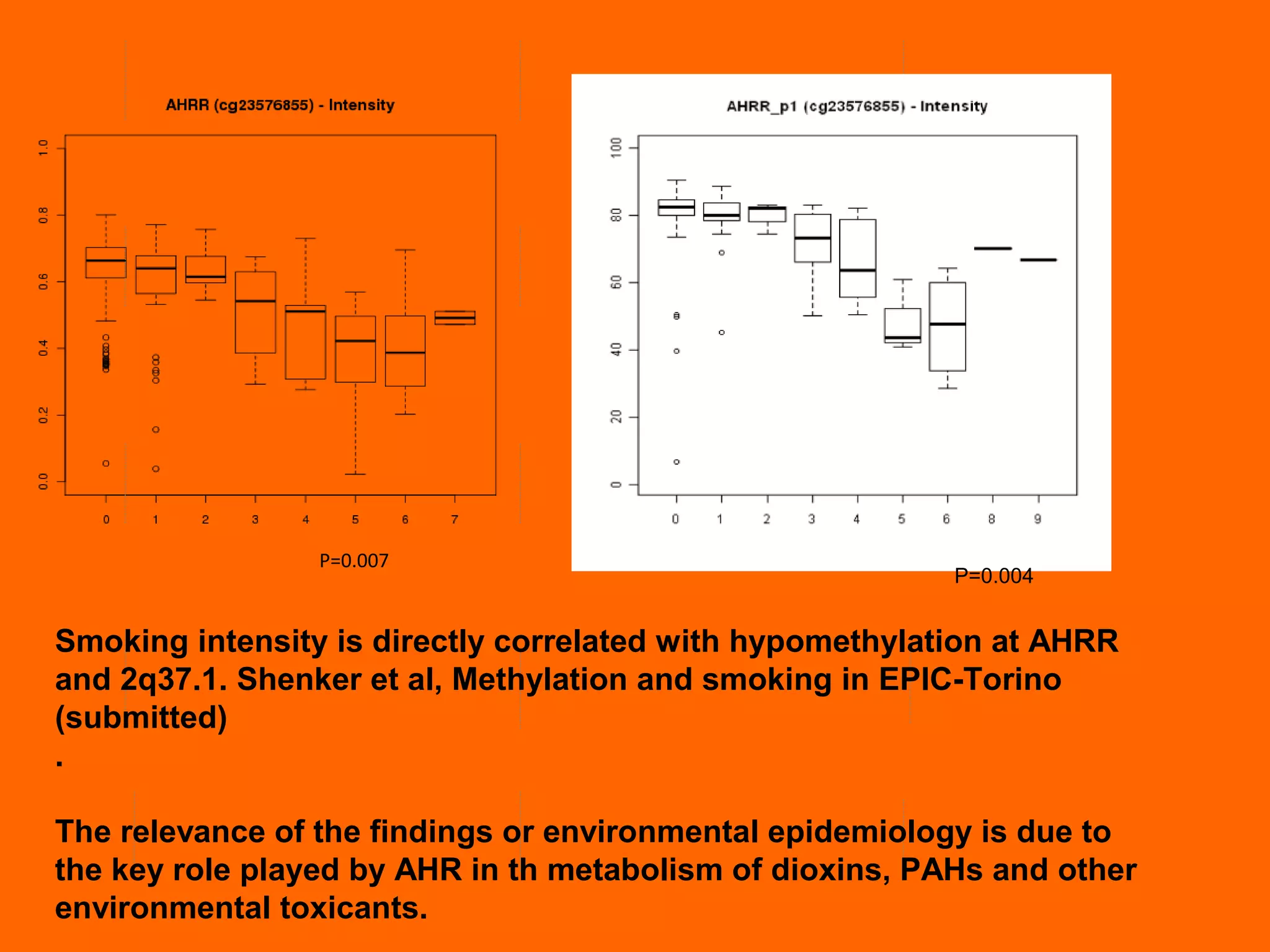

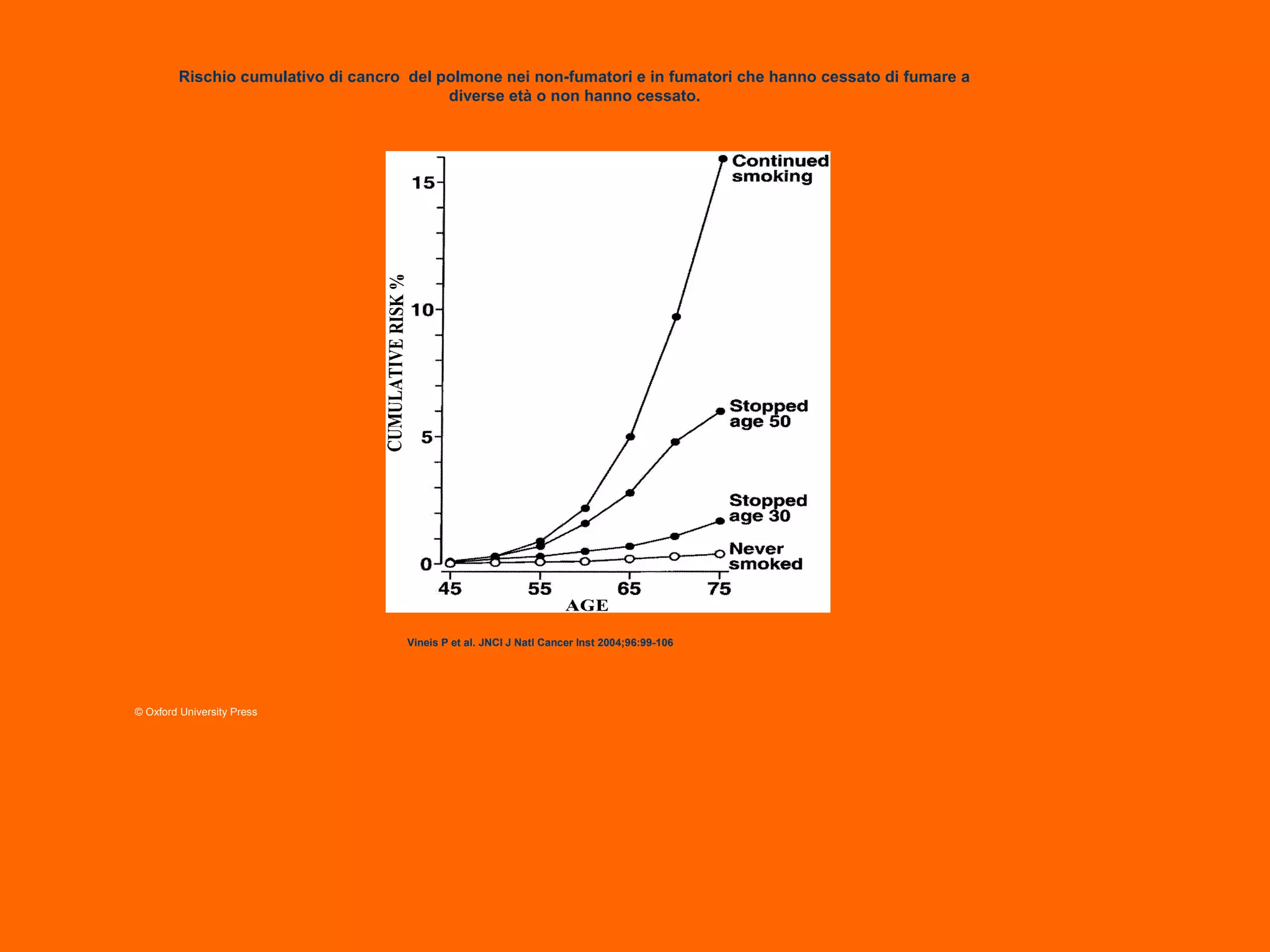

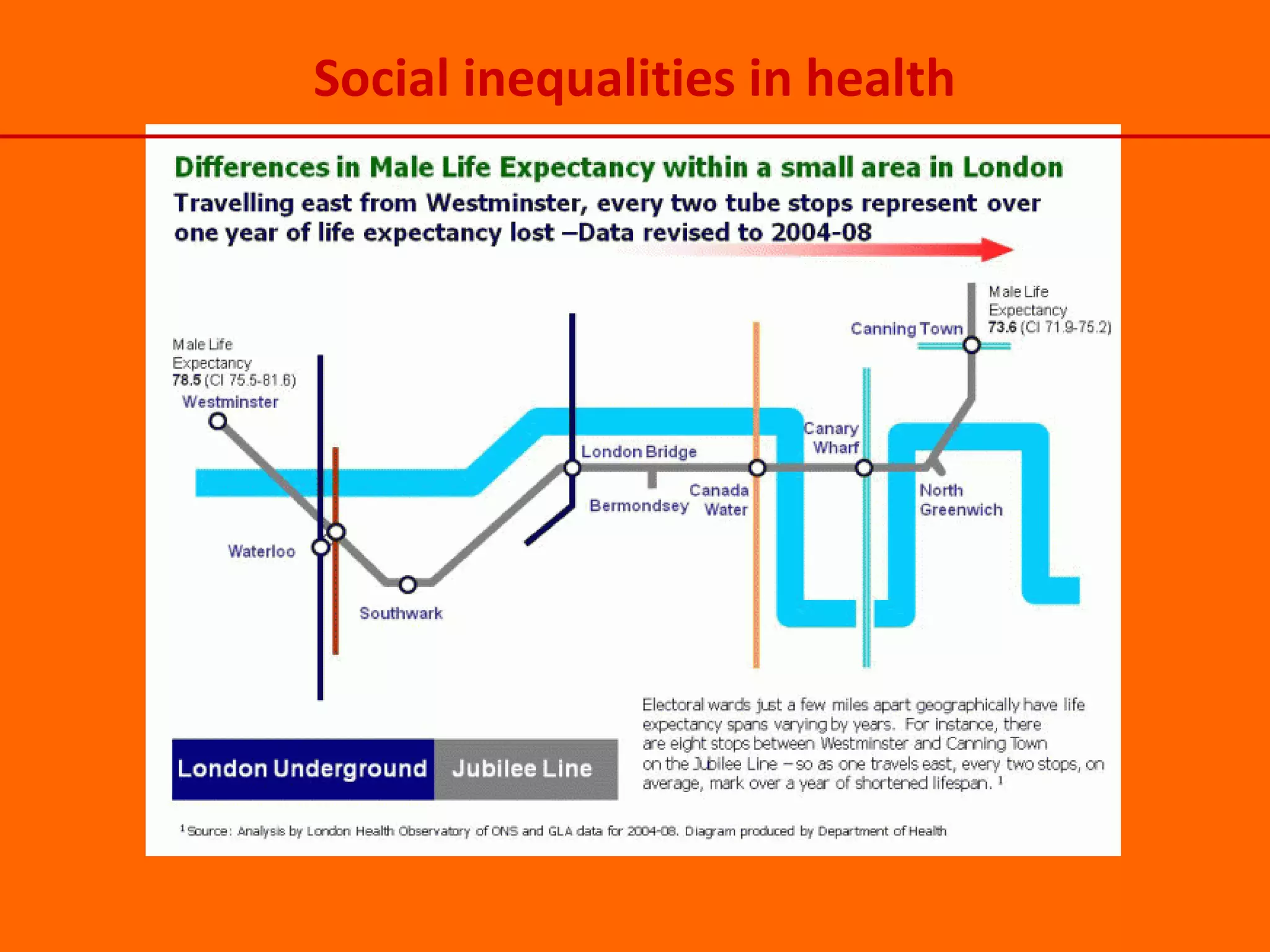

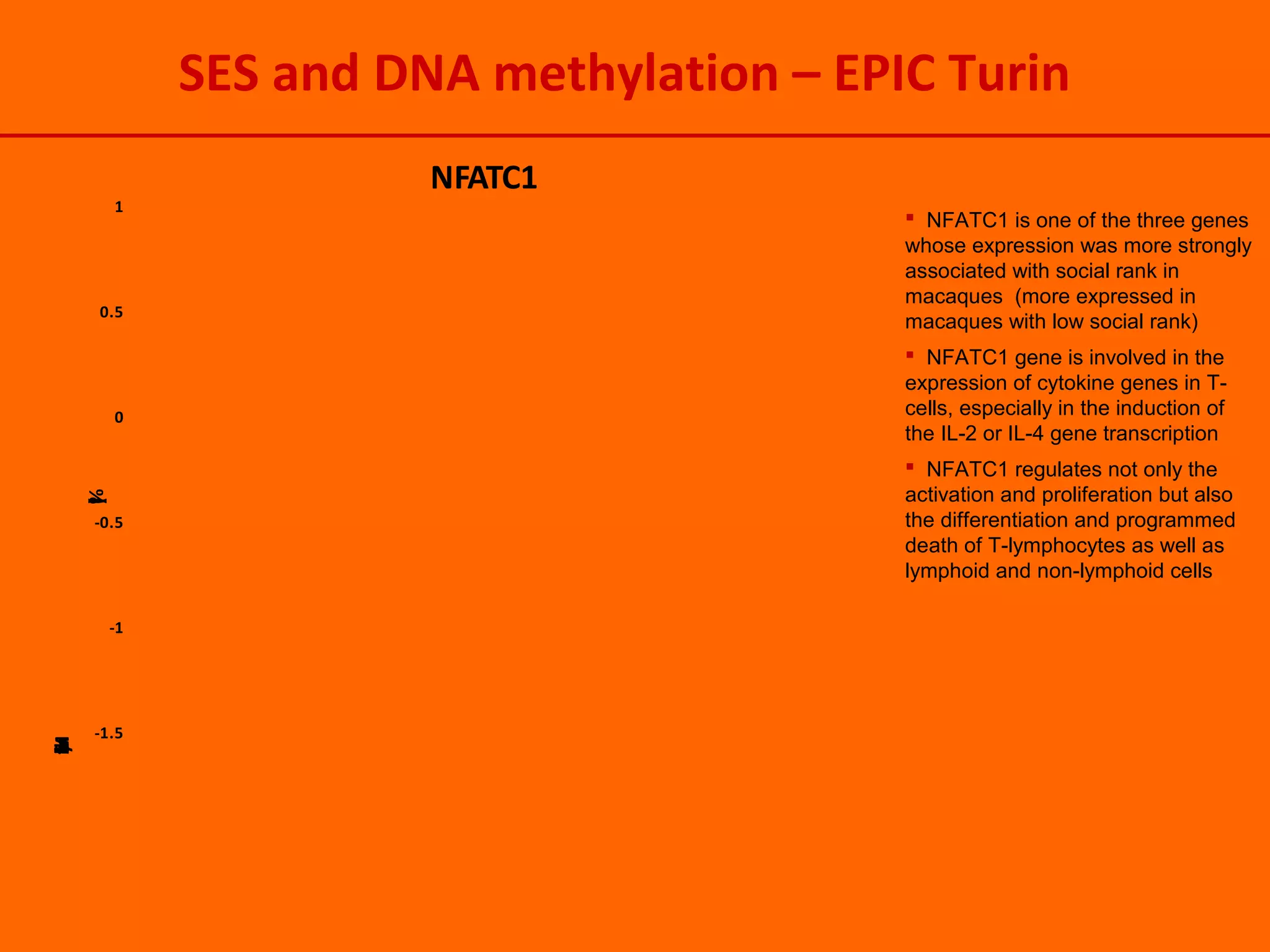

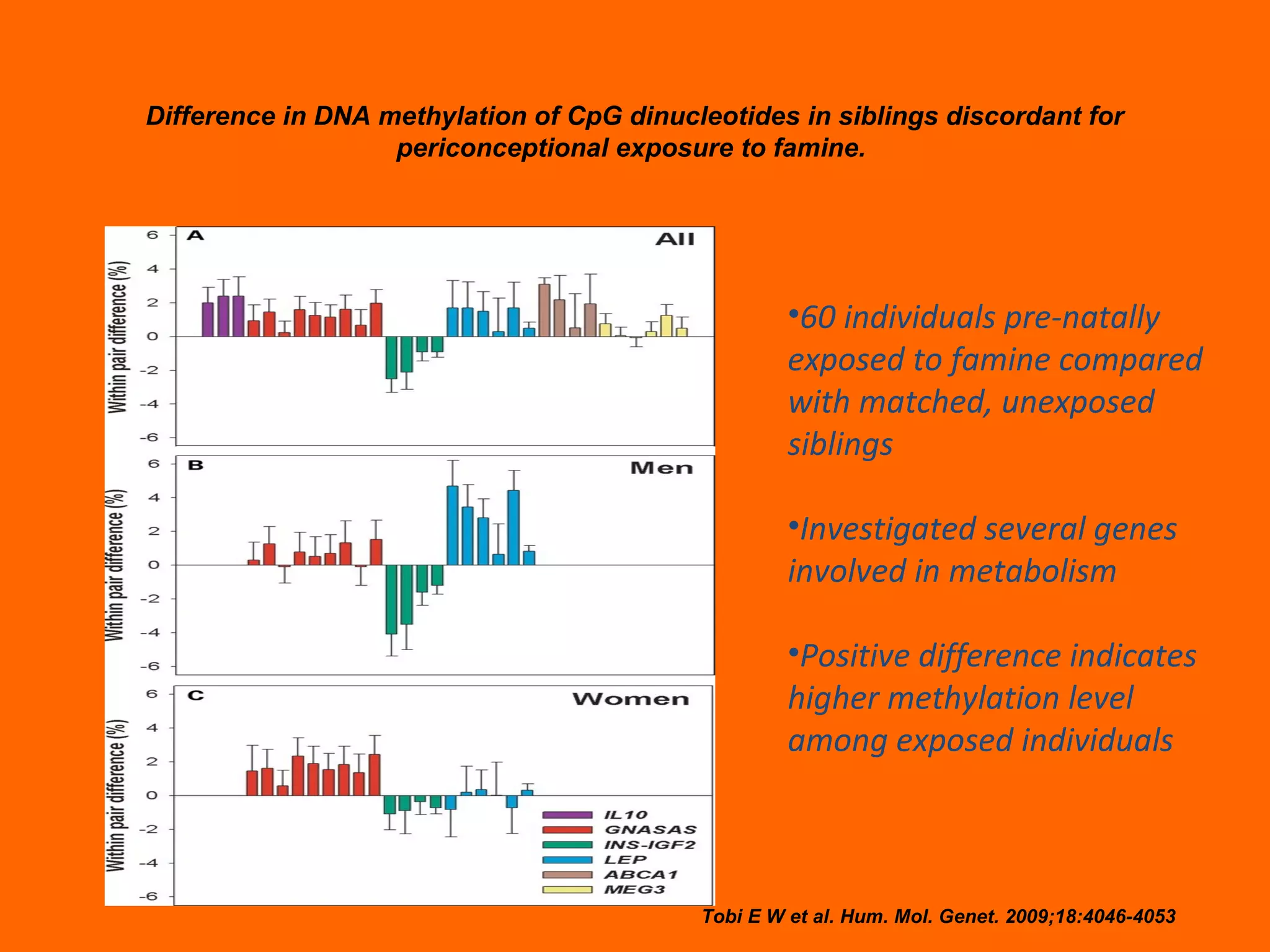

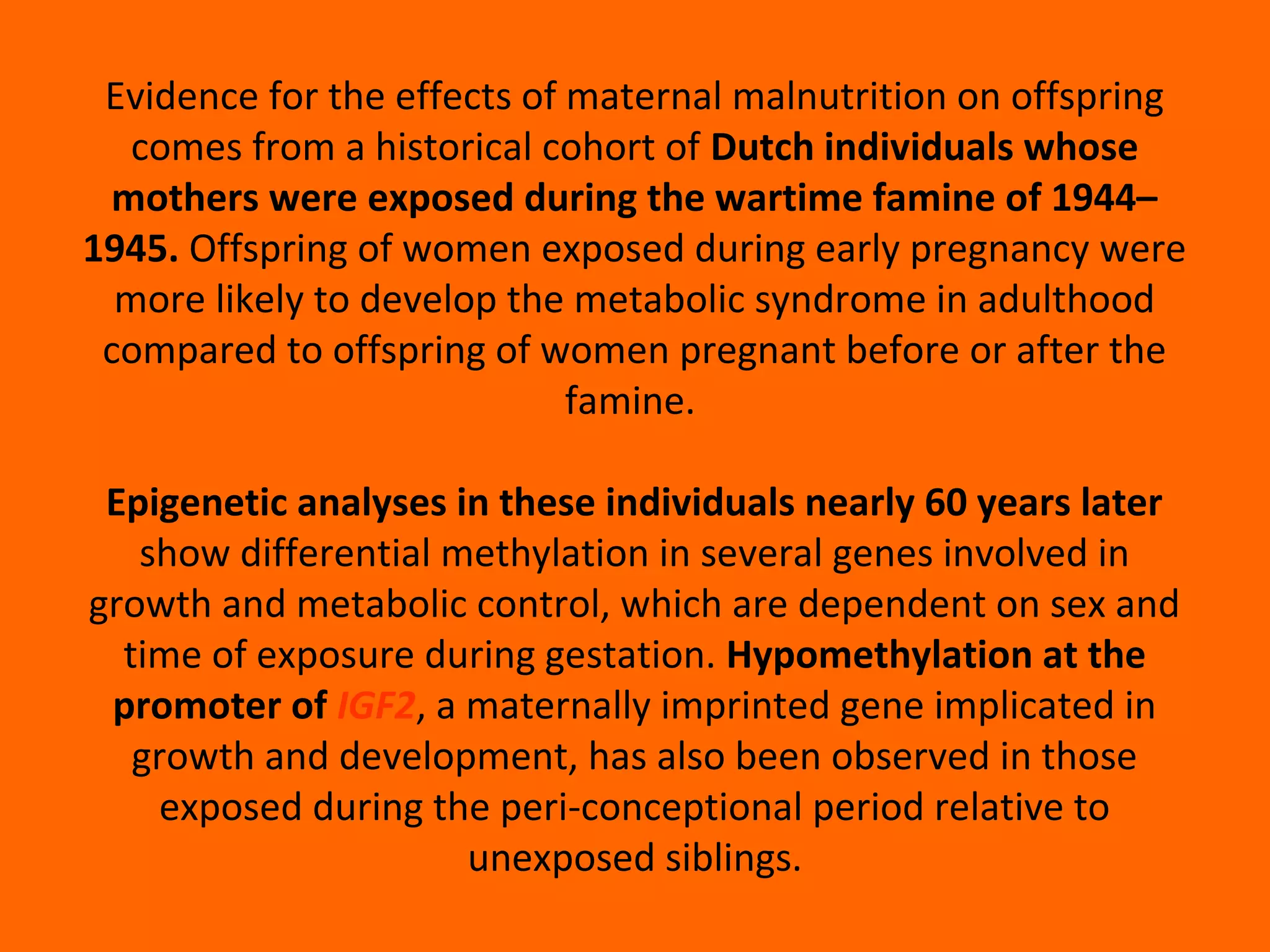

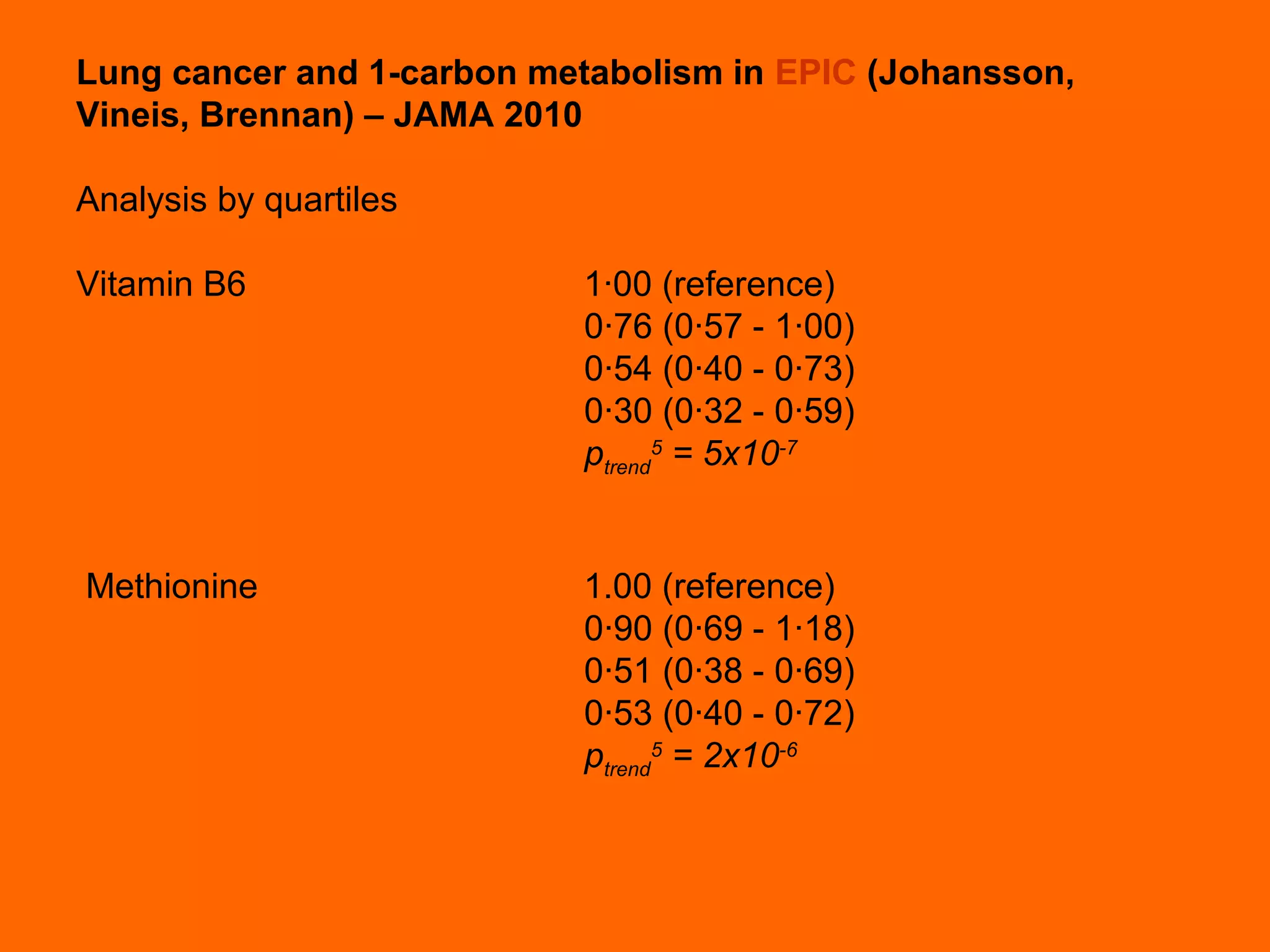

3. The role of epigenetics in cancer, development, and how the environment can influence epigenetic changes. Diet, smoking, socioeconomic status, and toxins are discussed as environmental factors that can cause epigenetic modifications.