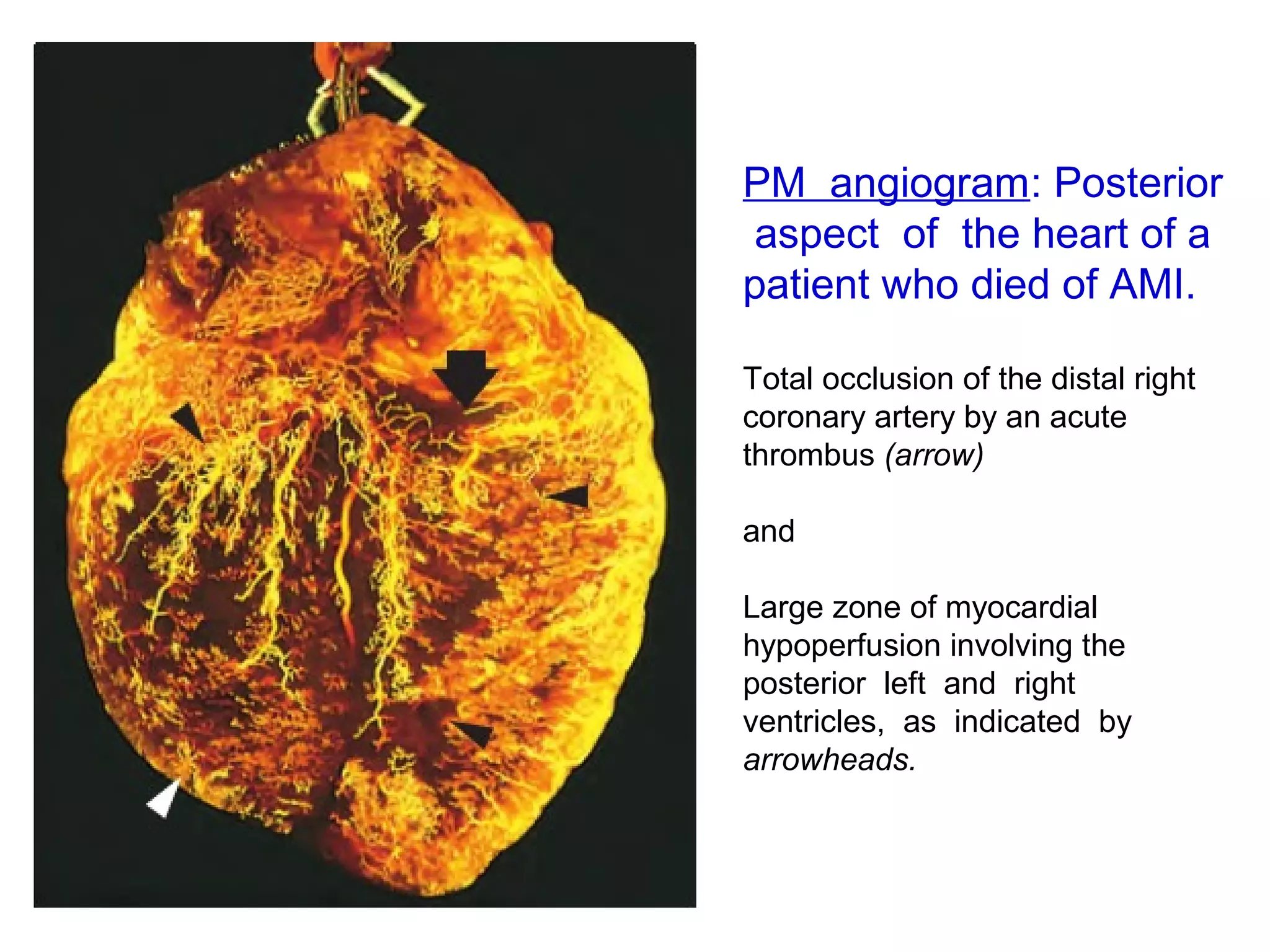

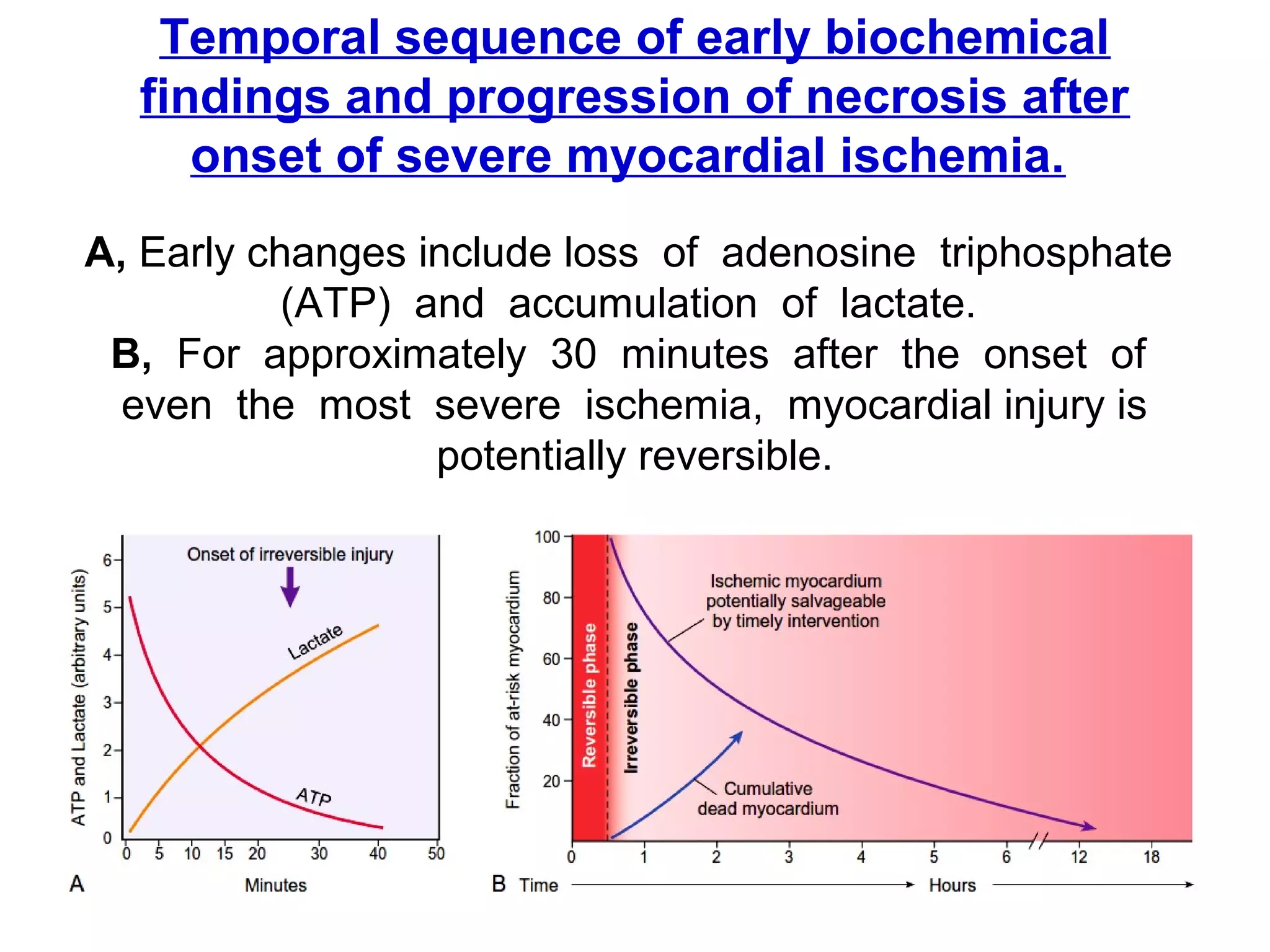

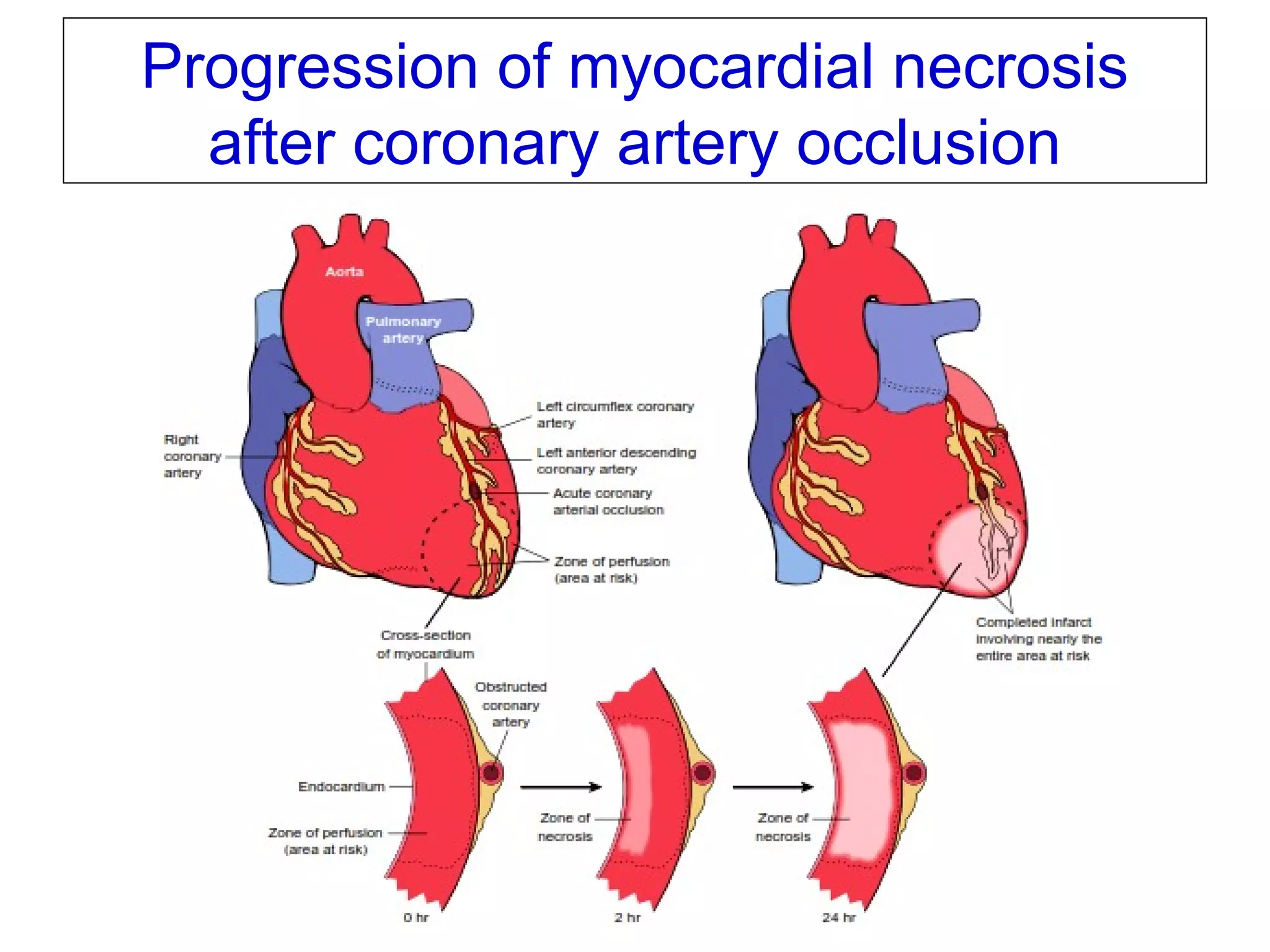

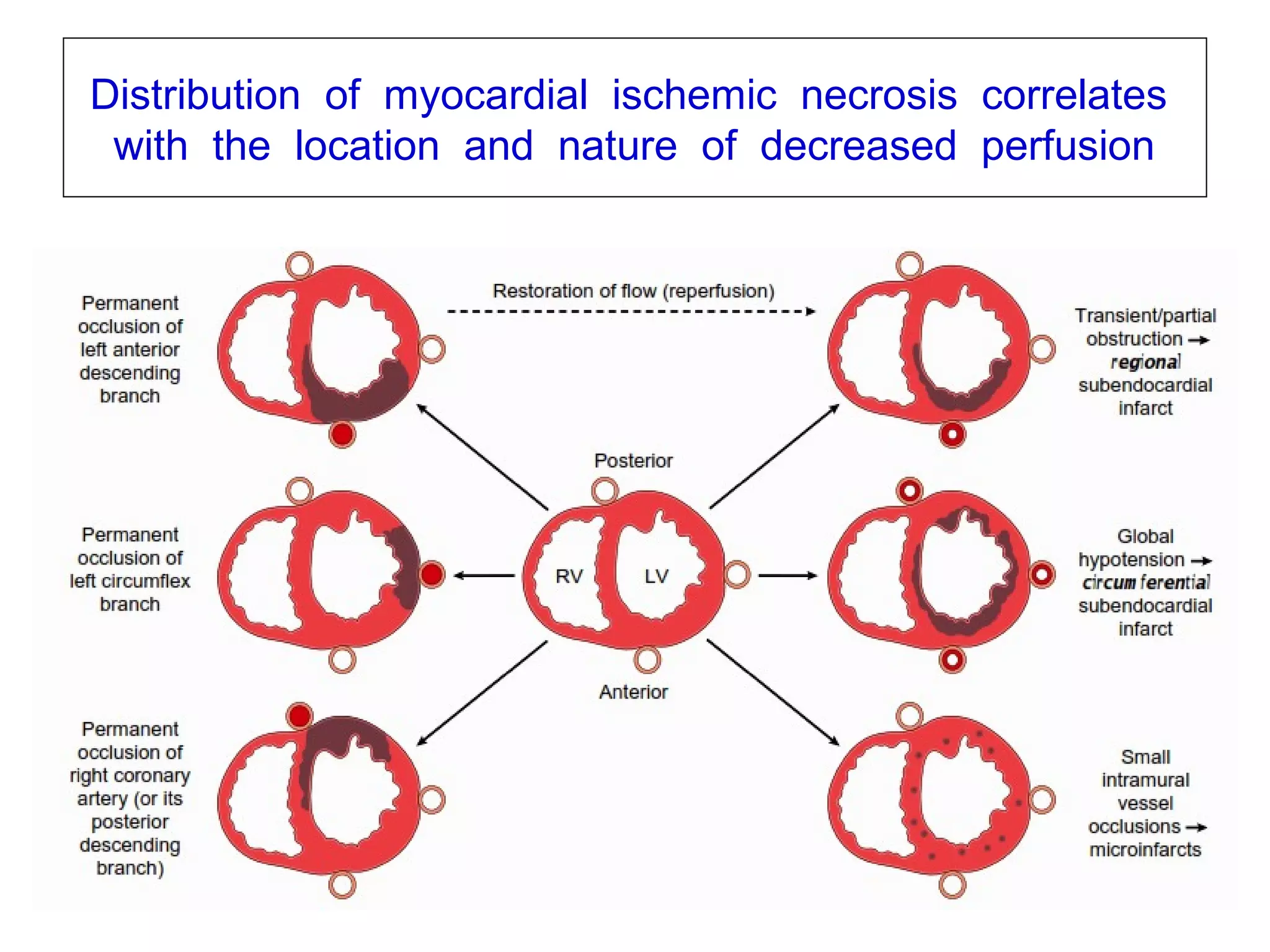

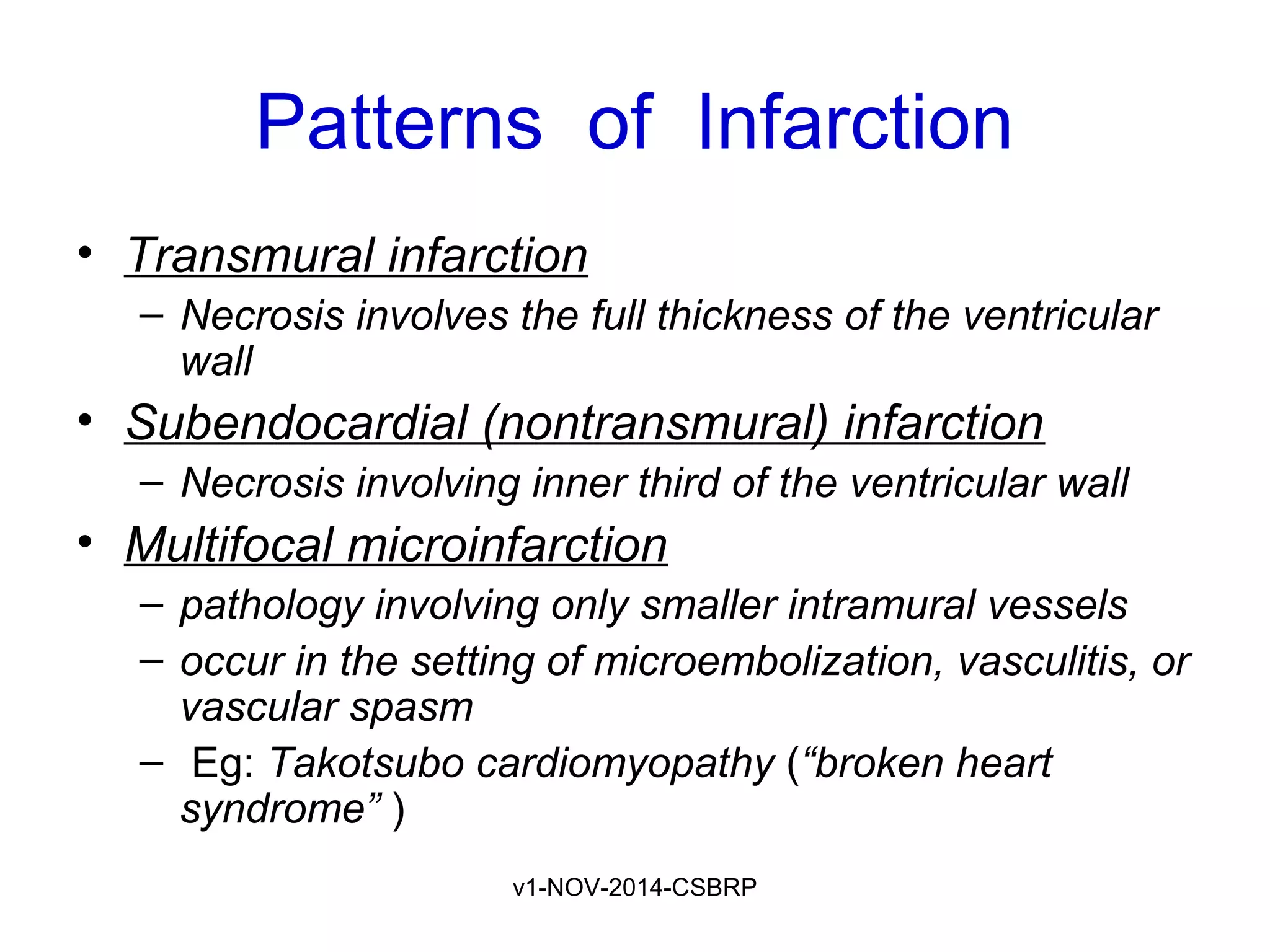

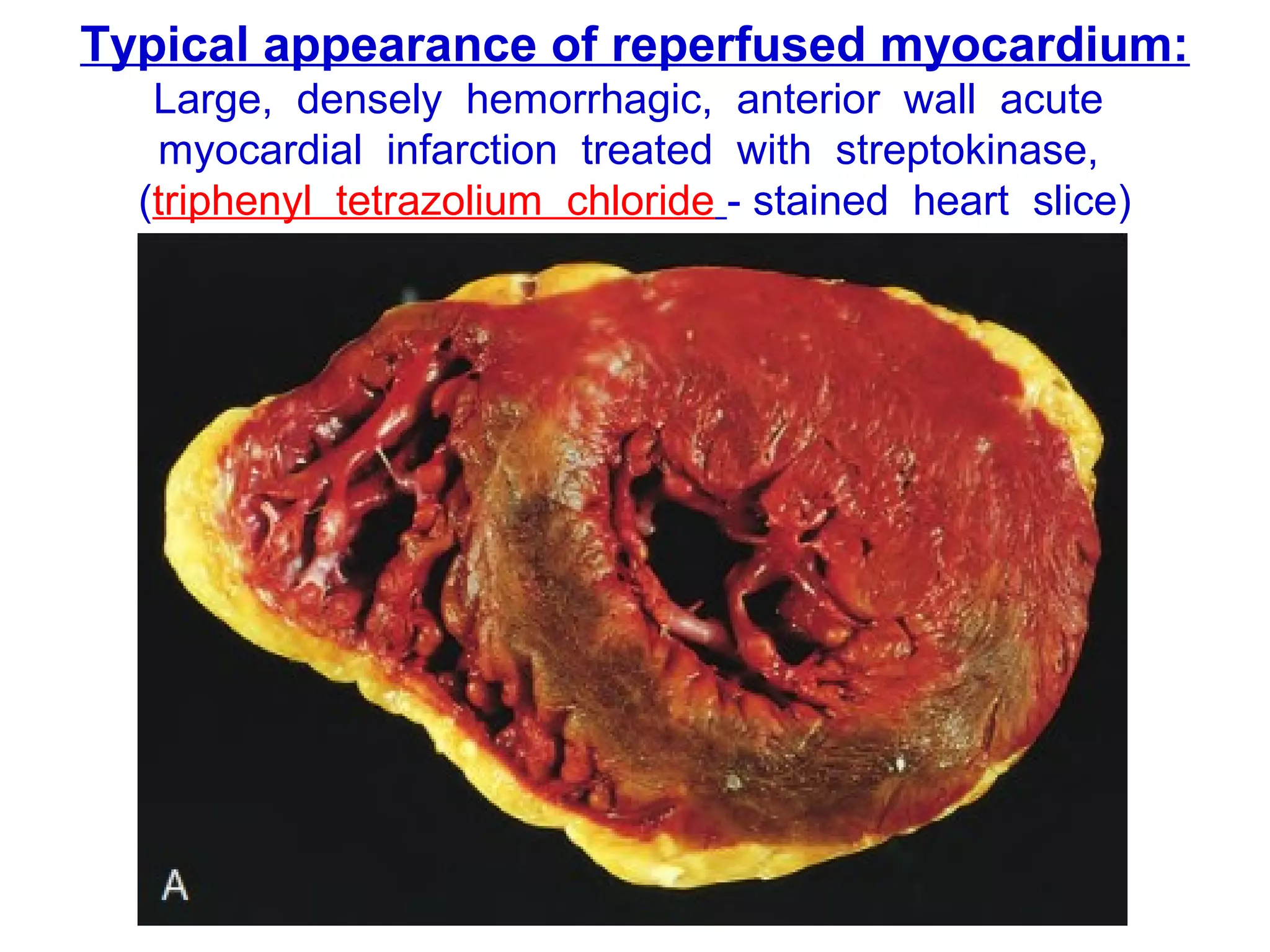

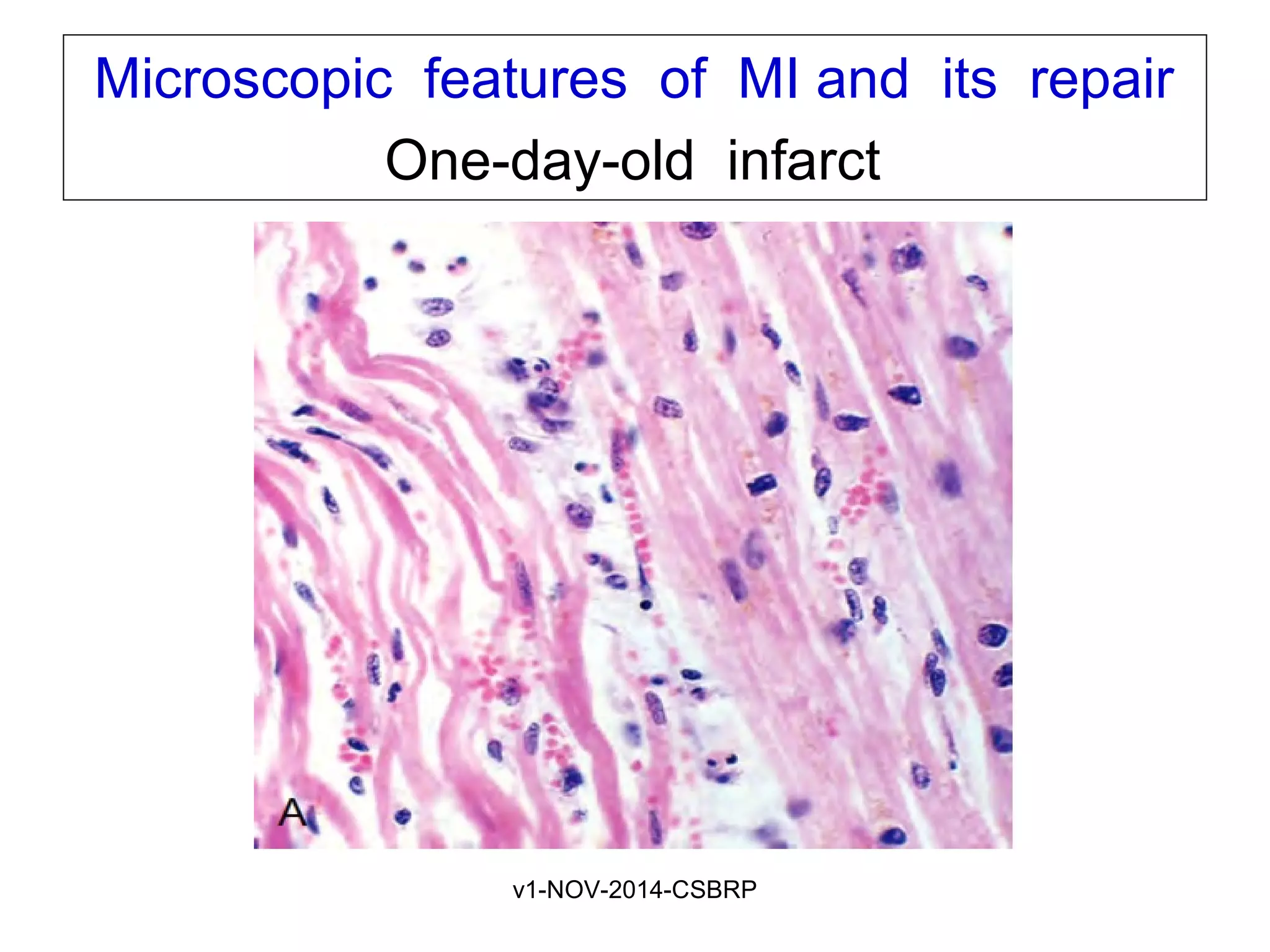

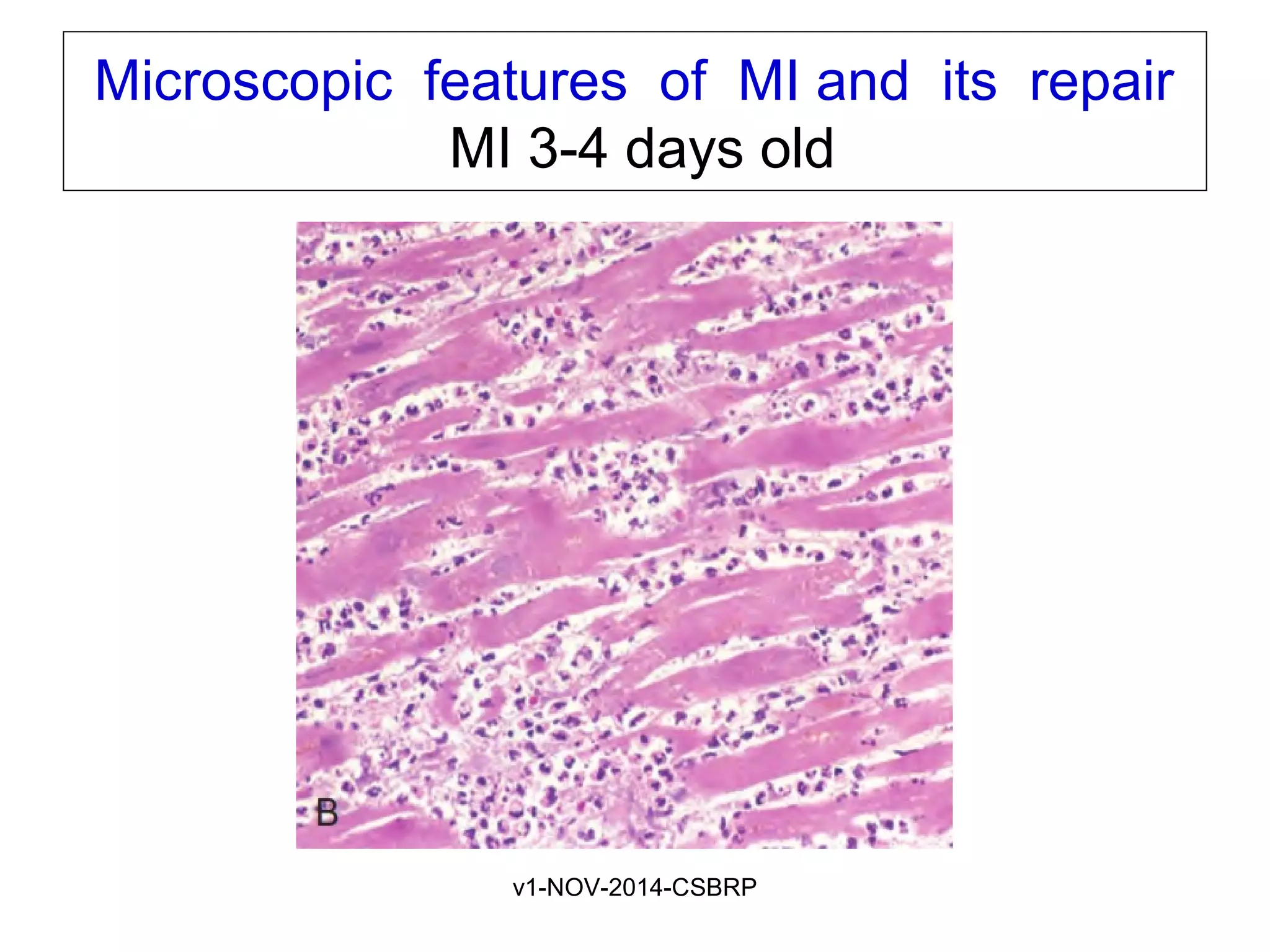

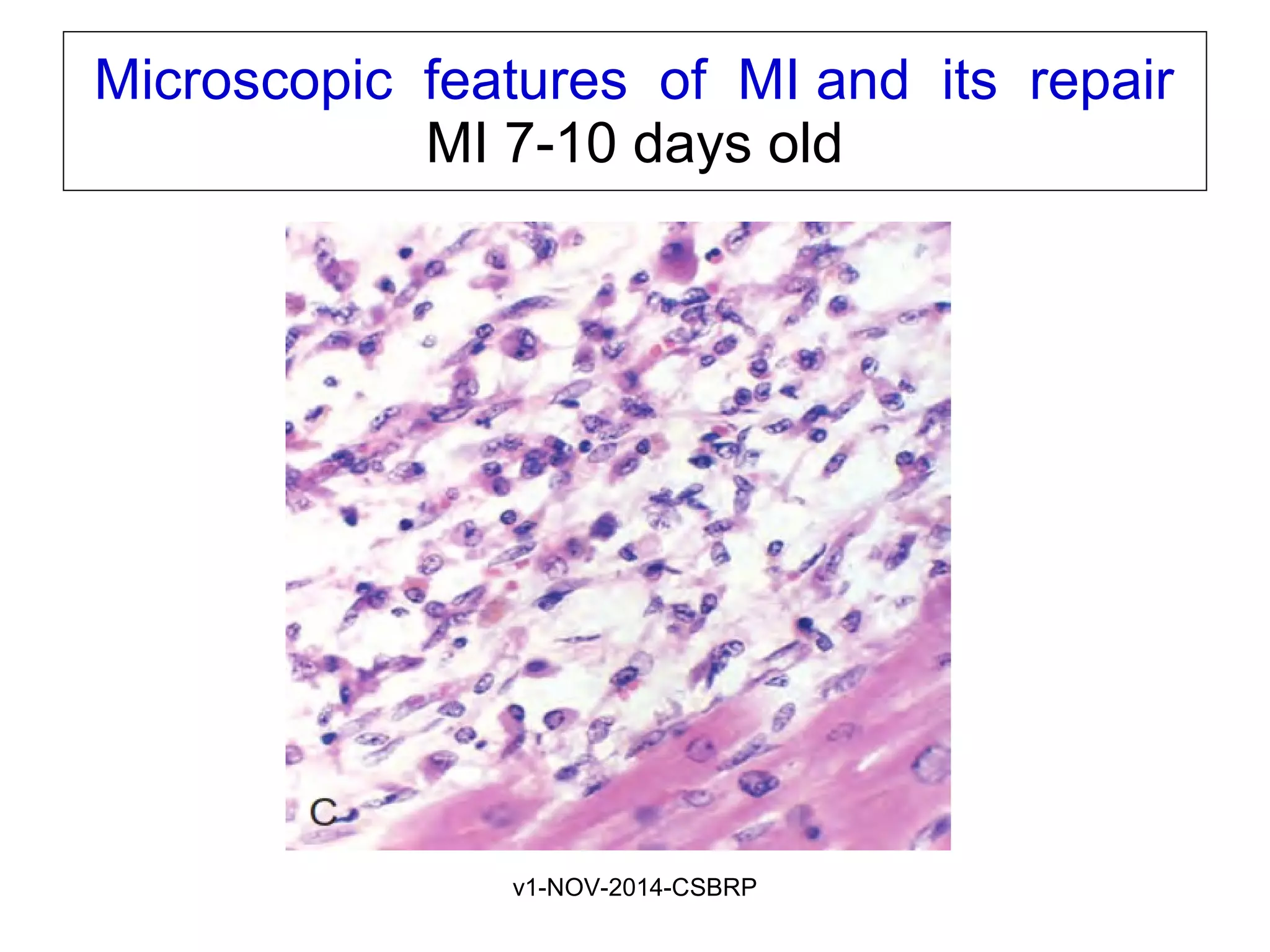

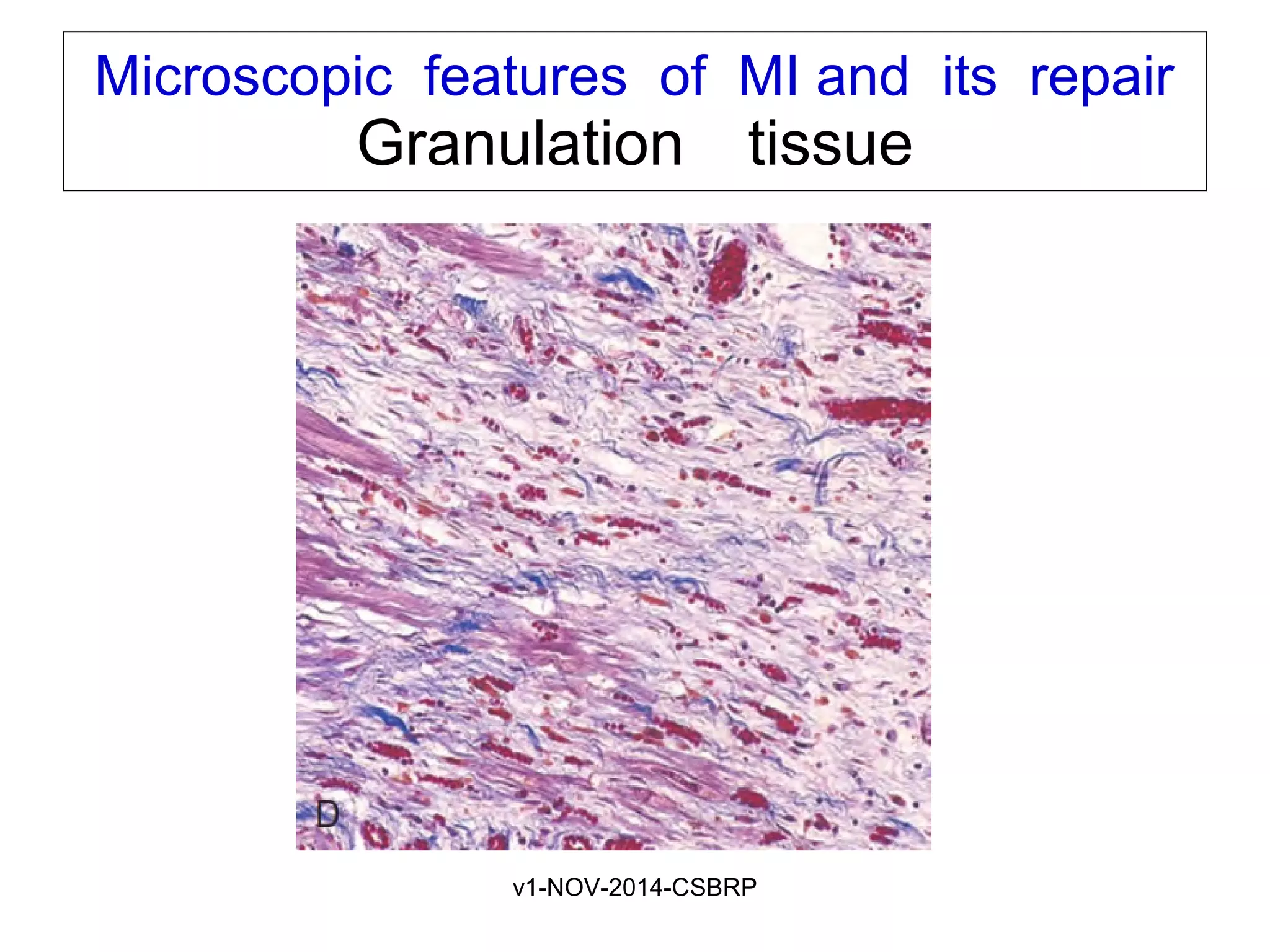

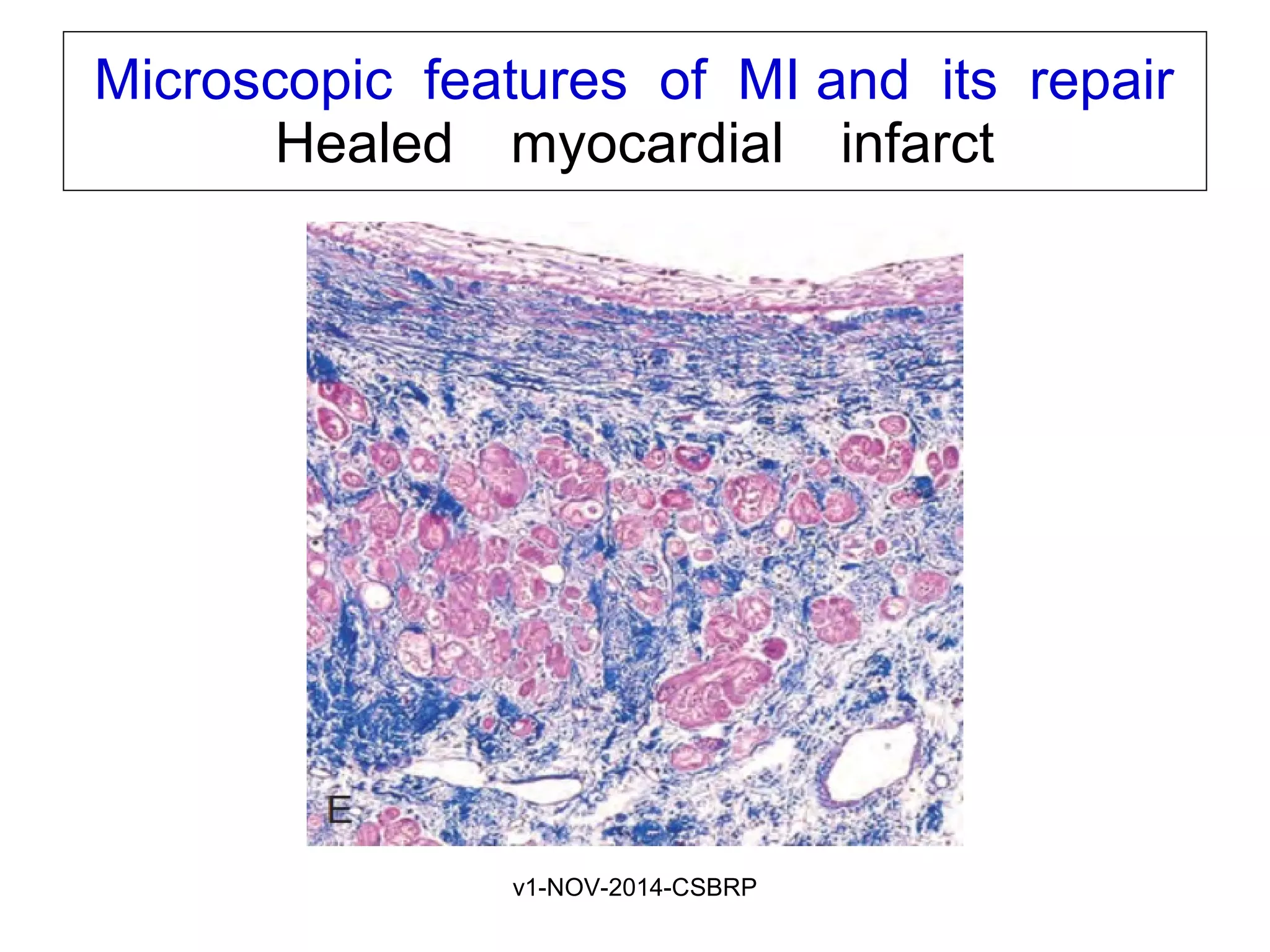

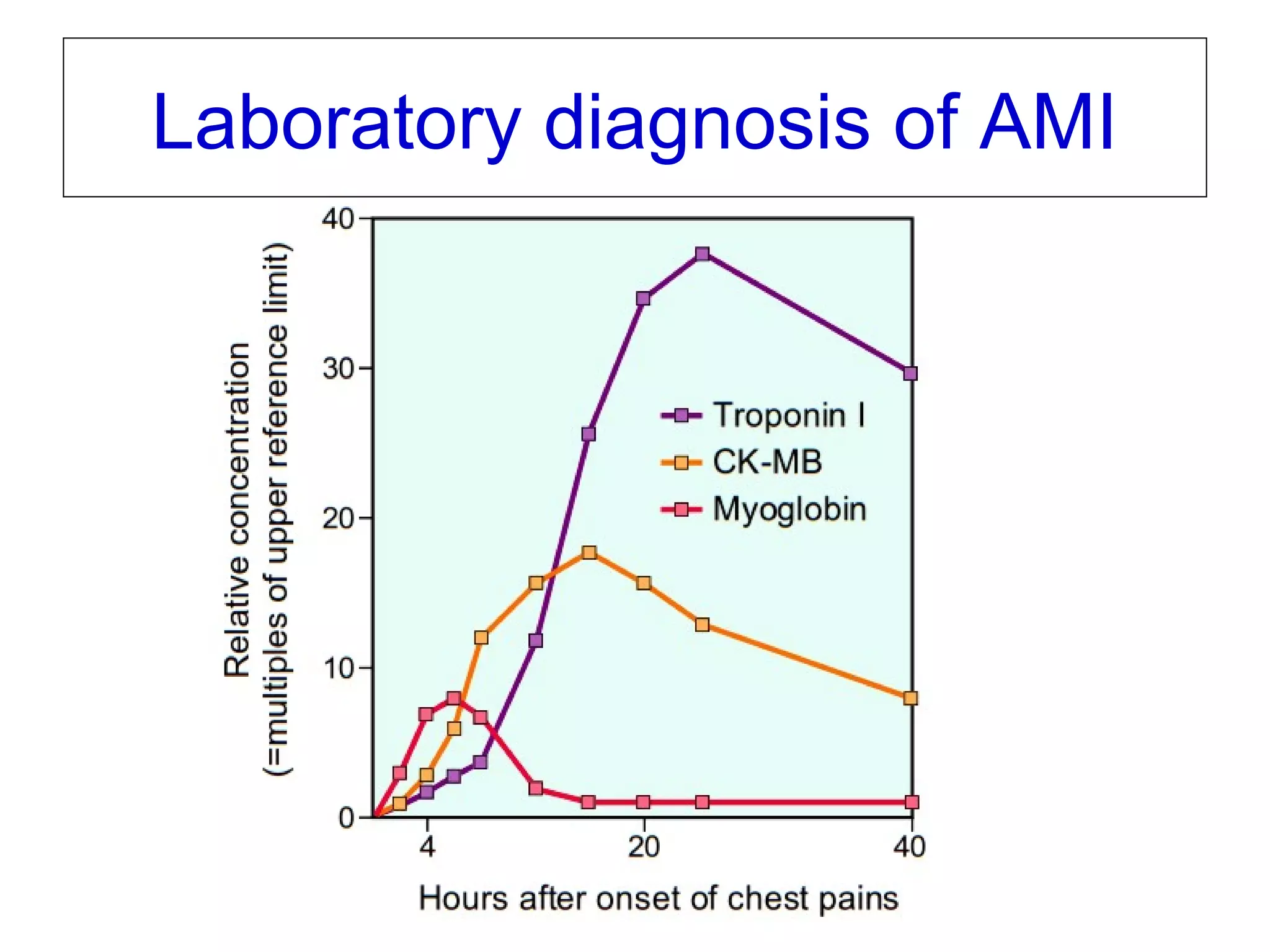

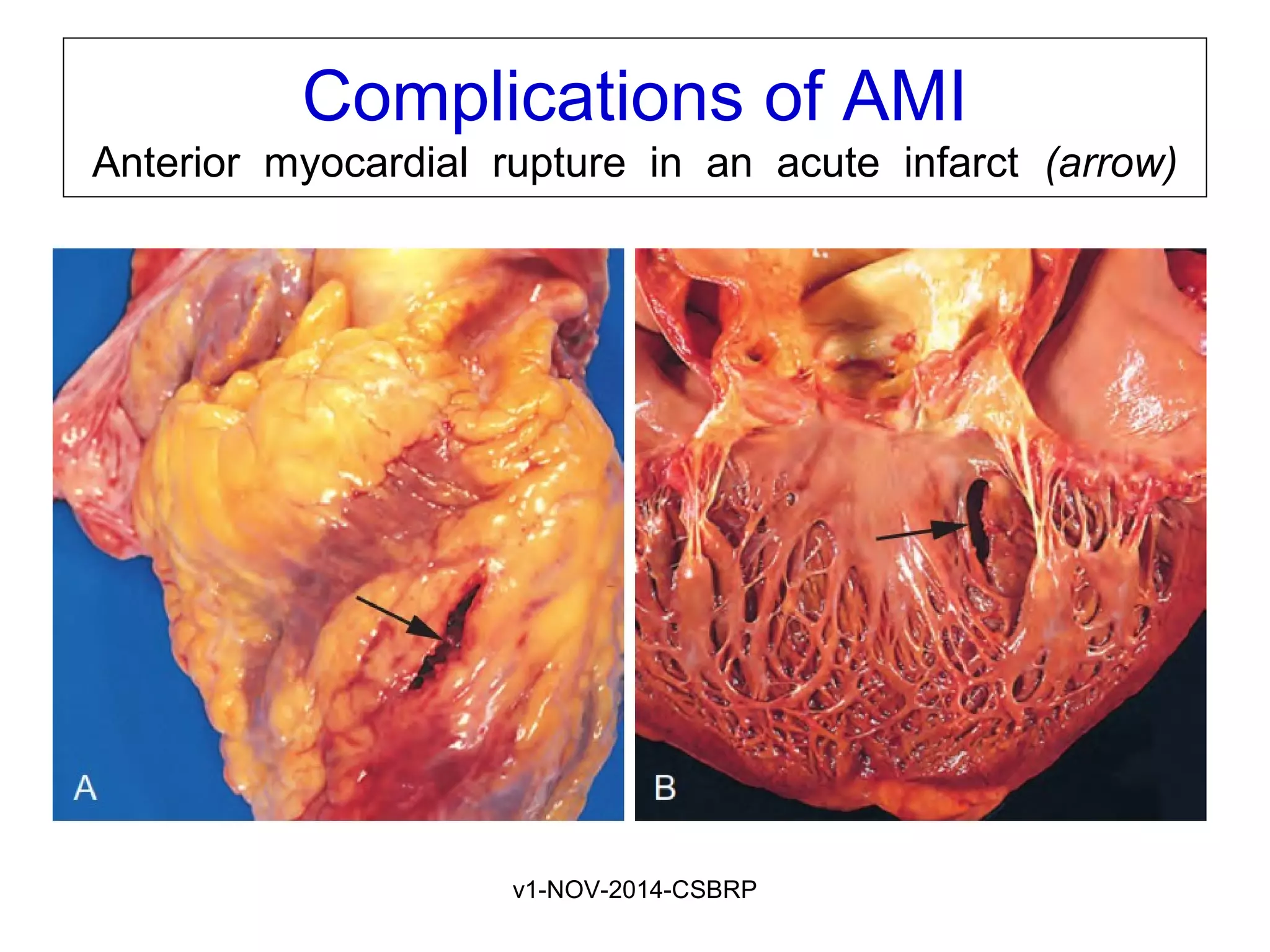

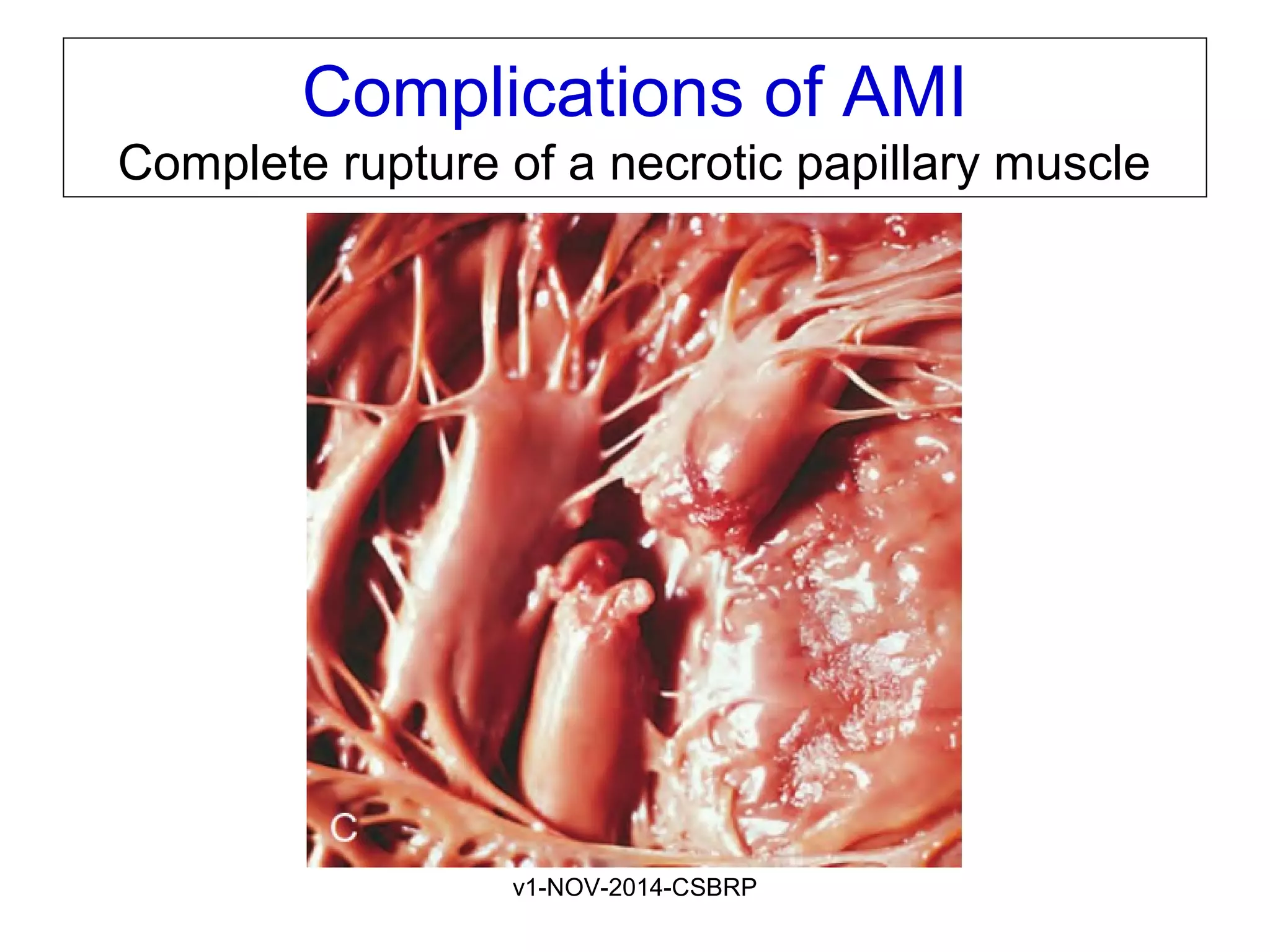

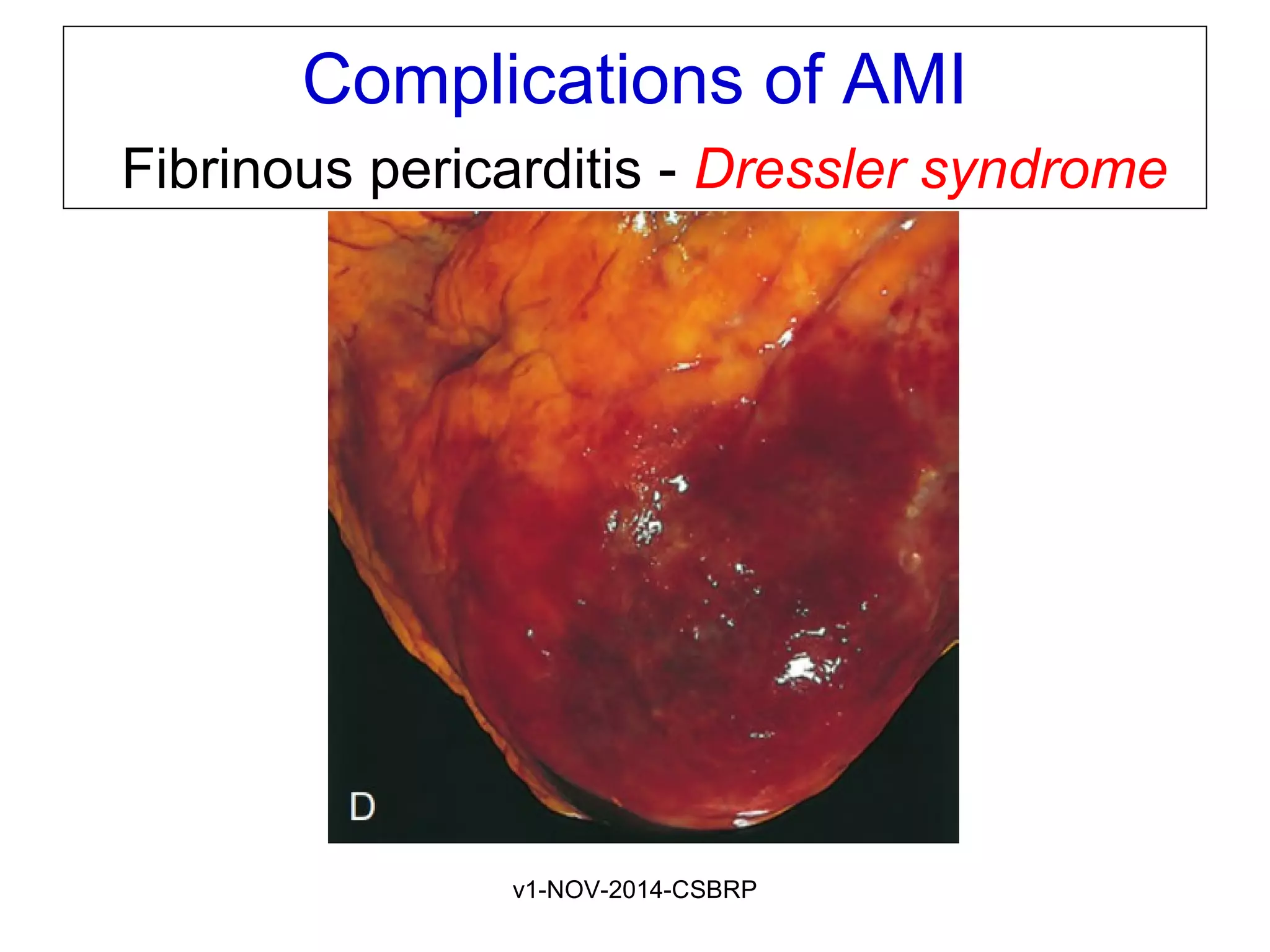

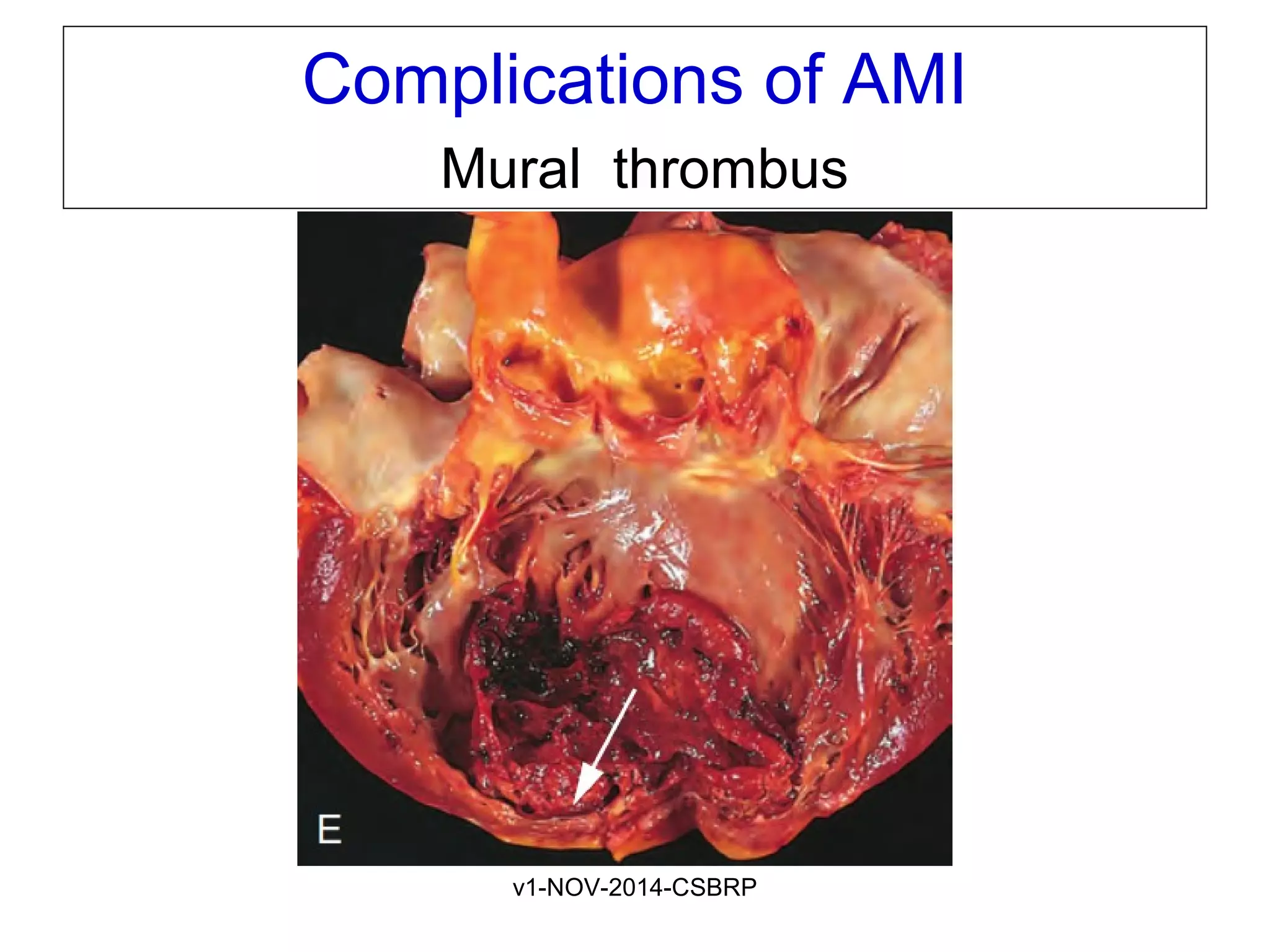

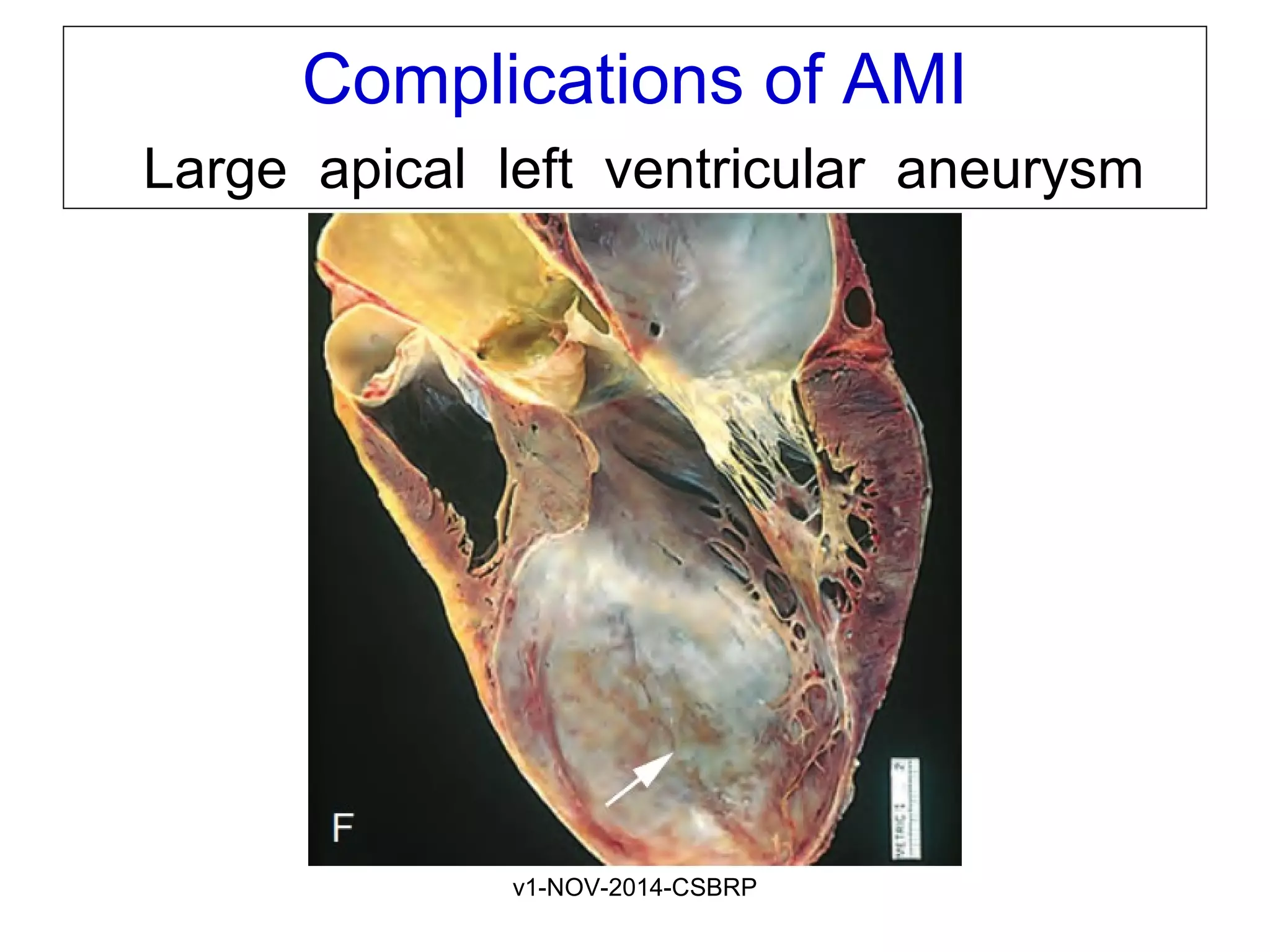

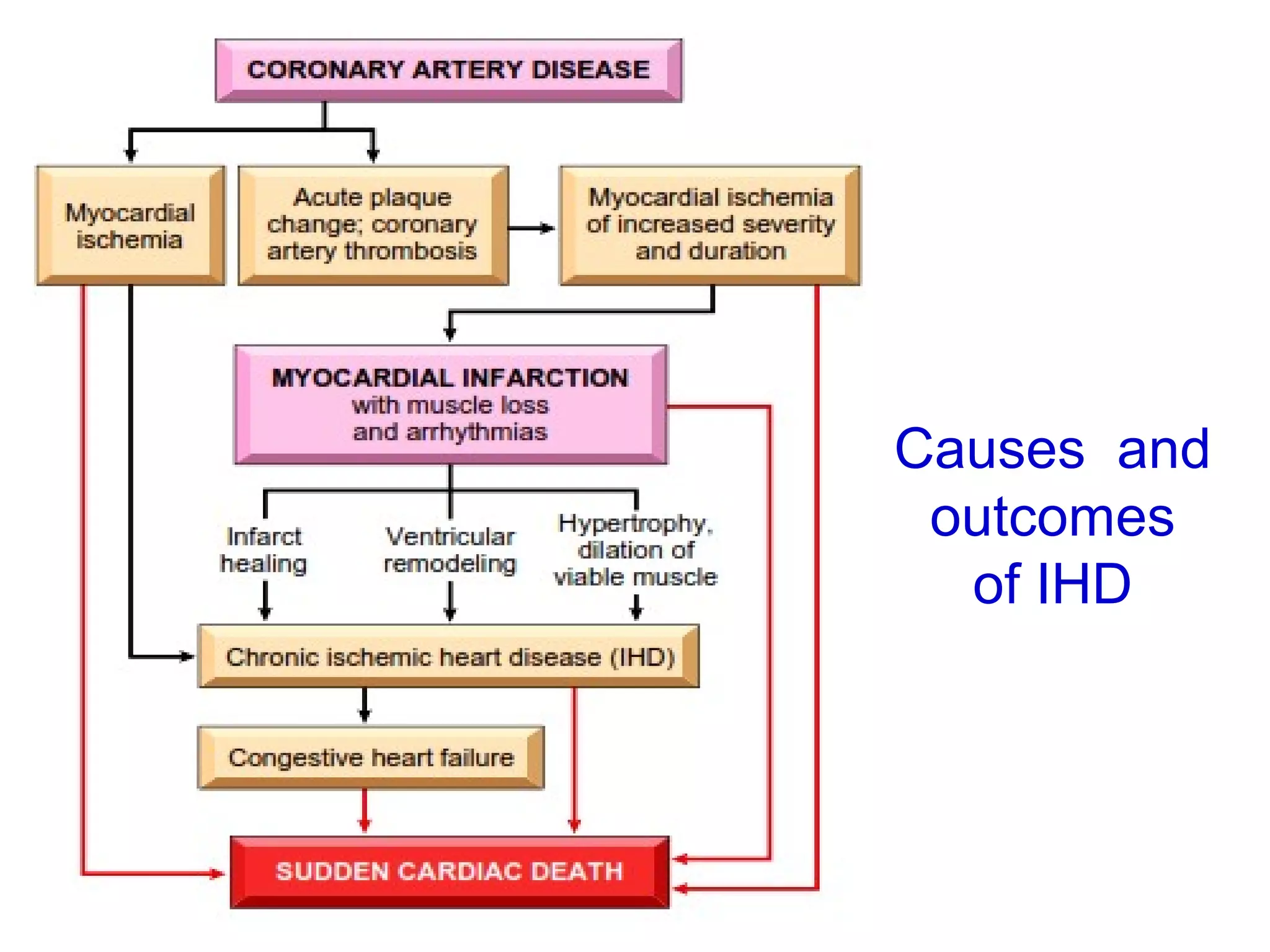

The document discusses acute myocardial infarction (AMI), including the pathophysiology of AMI, patterns of infarction seen on ECG and microscopy, effects of reperfusion therapy, complications of AMI, and chronic ischemic heart disease. It provides images demonstrating features of AMI such as areas of necrosis, effects of reperfusion, and complications. The goal of reperfusion therapy is to limit infarct size and salvage cardiac muscle.