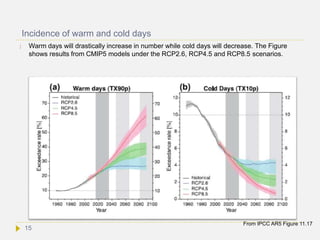

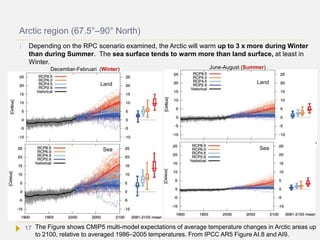

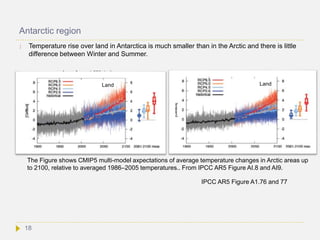

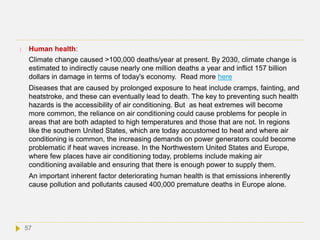

Climate models use mathematical equations and global grids to simulate and predict climate conditions based on physical principles and observational data. They show reasonable agreement with past climate trends and are used to project future climate change under different greenhouse gas emission scenarios. However, uncertainties remain regarding some processes like cloud formation. Current models estimate global warming of 0.3-1.7°C by 2100 under a low emission scenario and 2.6-4.8°C under high emissions, with greater warming over land and in polar regions. The models also predict more hot days and heat waves along with rising sea levels.

![ Reliability of climate models has to be tested against what happened with climate in the

past.[125] If a model can correctly simulate trends from a particular starting point somewhere

in the past, it can be used to predict with reasonable certainty what might happen in the

future. However, different models include different entry elements and may therefore

generate different predictions. Results can also vary due to different greenhouse gas or

aerosol inputs, the model's climate sensitivity to greenhouse gases (= the change in

temperature upon doubling of CO2 in the atmosphere), the use of differing estimates of

future greenhouse gas emissions (for example the rate of methane leakage during shale

gas extraction) and so on. A model-based prediction is therefore presented under different

scenarios with respect to humanity’s future demographic expansion and behavior. Which

scenarios are most realistic is uncertain, as the projections of future greenhouse gas and

aerosol emission are themselves uncertain.

Certain processes represented in the model may be too complex or too small-scale to be

physically represented in the model. In that case the process is replaced by a simplified

process. This manipulation is known as parameterization. Various parameters are used in

these simplified processes. An example are clouds. Cloud formation is notoriously complex

and climate model gridboxes for clouds have a resolution of 5 km, which is much larger than

the scale of a typical cumulus cloud (1 km). Therefore the processes that such clouds

represent are parameterized.

Because of simplification by parameterization and uncertainty in scenarios, climate models

always enclose estimates of uncertainty levels.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-4-320.jpg)

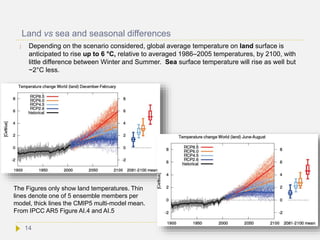

![Reliability of climate models

Models have accurately predicted climate change trends in the past. For example, the

vulcanic eruption of Mt. Pinatubo allowed to test the accuracy of models by entering the

eruption data and then observe how climate changed. The observed climatic response was

found consistent with the prediction. Predictions of atmospheric CO2 levels made by IPCC

in 1990 were also fully confirmed by the later observations (see slides on ‘Climate change in

the atmosphere’). Models also correctly predicted greater warming in the Arctic and over

land, greater warming at night, and stratospheric cooling.

Other predictions underestimated climate change, such as arctic ice melting and sea

level rise predicted by the IPCC Third Assessment report. Precipitation rates also

increased significantly faster than global climate models predicted.

Still others slightly over-estimated the rise in atmospheric methane concentrations (see

IPCC AR5 WG1).

An important uncertainty factor in climate predictions is climate sensitivity – being the

temperature response to a doubling of the atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration –,

because it is affected by climate feedbacks. Higher climate sensitivity will result in more

warming, in case of a positive feedback.[Ref] If a negative feedback is acting, a given

greenhouse gas rise will result in less sensitivity.

Climate models are still not well predicting the effect of clouds [Ref] , due to lack in

knowledge of cloud generation processes. Uncertainties in methane release from

permafrost and leakage during methane extraction from shale gas by fracking, are other

examples of prediction uncertainties.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-6-320.jpg)

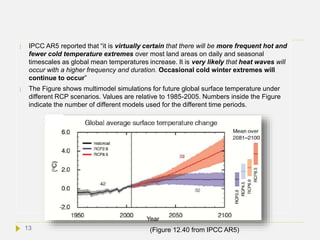

![Climate sensitivity

Projections of climate change in the future are dependent on the sensitivity of the climate

system to the greenhouse radiative forcing. It is therefore essential to have an accurate

estimate of this sensitivity. Climate sensitivity is a measure of the surface temperature change

in °C per W/m2 sustained radiative forcing. In practice it is expressed as the temperature

change associated with a doubling of the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere relative

to pre-industrial levels (~280 ppm). There are two ways to look at climate senstivity:

equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and transient climate sensitivity (TCS). The former is

calculated over the time span needed to reach full equilibrium between sustained CO2

forcing and the climate system. TCS is defined as the average temperature response over a 20-

year period to CO2 doubling with CO2 increasing at 1% per year.[Ref] TCS is lower than ECS,

due to the "inertia" (slowliness) of ocean heat uptake and ice sheet feedbacks.

Doubling CO2 level results in forcing of 3.7 W/m2. In a simple physical environment a doubling

of CO2 would result in 1 °C warming. However, in the real atmosphere complex positive and

negative feedbacks are operating (water vapor, cloud and ice albedo, aerosols, ozone…),

influencing radiative forcing. The net warming effect was found to be ~3 times higher.

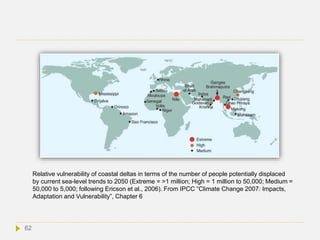

Feedbacks can also become stronger with time. For example ice sheets may melt at a given

time point at a much faster rate due to a sudden collapse of large ice shelves allowing massive

release of ice into the sea. Icebergs drift away to warmer water and melt, hereby decreasing

albedo, resulting in more warming. Addition of these longterm feedbacks to climate

models was found to lead to a higher value of ECS, but most climate models have not

included these feedbacks yet. Thus, future climate change may be more deleterious than

presently expected.

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-7-320.jpg)

![ Current climate models span an ECS range of 2.6–4.1 °C, most clustering around 3 °C."[Ref]

The IPCC AR5 concensus value of ECS, calculated by multimodel ensembles, is between

1.5°C and 4.5°C, is extremely unlikely <1°C, and very unlikely >6°C. Notice that

feedback contribution, being not constant over time, induces a level of uncertainty in any

climate model.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-8-320.jpg)

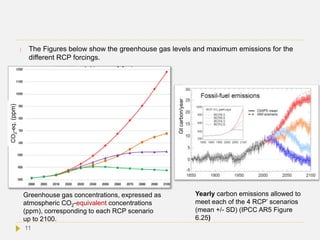

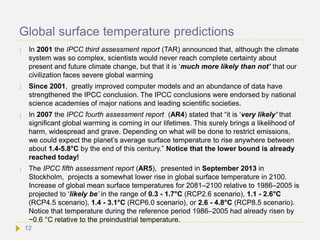

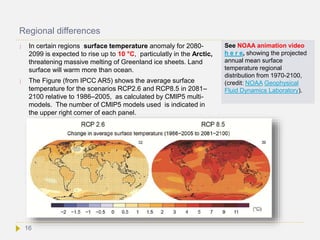

![IPCC radiative forcing scenarios

IPCC AR5 introduced a new set of scenarios, to project future climate change with

climate model simulations. These scenarios are called RCPs (Representative

Concentration Pathways). These are based on the radiative forcing that emission

rates would cause in the years to come. The main RCPs are RCP2.6, RCP4.5,

RCP6.0, and RCP8.5, named after the radiative forcing values that are projected

for the year 2100 i.e. +2.6, +4.5, +6.0, and +8.5 W/m2, respectively.[2]

In the RCP8.5 scenario radiative forcing is set to reach 8.5 W/m2 by 2100 and to

continue to rise for some time thereafter. RCP6.0 and RCP4.5 are intermediate

“stabilization pathways”, where radiative forcing does not further rise after 2100. In

the RCP2.6 scenario, radiative forcing peaks at 3 W/m2 before 2050 and then declines

to 2.6 by 2100.

To each forcing scenario there is a corresponding greenhouse gas level in the

atmosphere (see next slides). In order to remain within this future greenhouse gas

concentrations adopted in the RCP scenarios, the maximum cumulative fossil fuel

emissions should be not higher than 272 Gt, 780 Gt, 1062 Gt and 1687 Gt carbon

equivalents up to 2100 for RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5, respectively (see

next slides).

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-9-320.jpg)

![ Although theoretically possible, [Ref] RCP2.6 is a

scenario difficult to attain, since 1) in 2012

radiative forcing was already 2.9 W/m2, 2) to

realize RCP2.6, atmospheric CO2 must be

stabilized at 450 ppm (see next slide) which

requires a ~70% reduction of CO2 emissions

relative to the level in 2000 (see section 5). 3)

Both RCP2.6 and 4.5 scenarios already include

‘carbon dioxide removal’ (CDR) programs (see

section 5) to remain within the radiative forcing

limit and these CDR programs are presently

considered difficult to realize on a sufficient

global scale and with sufficient safety.

Trends in radiative forcing for 4 different

scenarios (IPCC RCP scenarios). Forcing is

relative to pre-industrial values and does not

include land use (albedo), dust, or nitrate

aerosol forcing (van Vuuren 2011).

Source

RCP8.5

RCP6.0

RCP4.5

RCP2.6

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-10-320.jpg)

![ Consistent with this result is that during the Middle Pliocene warm intervals, when

global mean temperature was 2°C–3.5°C higher than pre-industrial, ice-sheet models

calculated near-complete deglaciation of Greenland. Some scientists predict that

climate change may make the entire Greenland ice sheet melt in about 2,000 years.[2]

That alone would add 7m to sea level [3].

The surface mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet is projected to increase in most

models because increased snowfall outweighs melt increase. However, ice-shelf

decay due to oceanic or atmospheric warming might lead to abruptly accelerated ice

flow and loss into the sea. It remains uncertain whether East Antarctic ice sheet will

gain or loose mass [Ref]

Also James Hansen has argued that multiple positive feedbacks could lead to

nonlinear ice sheet disintegration by increased ice flow, calving and sudden ice

shelve collapses. More surface melt water would flow to the ice sheet bed, leading to

much faster melting of the ice interior.[Ref]. Moreover, as ice sheets shed ice more and

more rapidly, in ice streams, climate simulations indicate that a point will be reached

when the high latitude ocean surface cools while low latitudes surfaces are warming.

Larger temperature contrast between low and high latitudes will drive more

powerful storms.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-20-320.jpg)

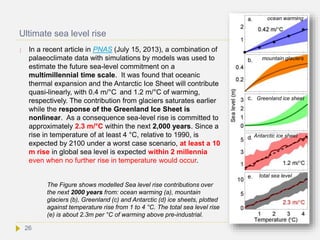

![Sea level rise

Sea level rise is expected to continue for

centuries, even millenia, even when

anthropogenic carbon emissions would

stabilize at the present level[13] This is

because the sea level contribution from ice

sheets continues over these time scales. In

2007, the IPCC AR4 projected that during the

21st century, sea level will rise another 18 to

59 cm, but these numbers do not include

"uncertainties in climate-carbon cycle

feedbacks nor do they include the full effects

of changes in ice sheet flow".[Ref] As shown in

the Figure, IPCC AR5 predicts similar sea

level rise. Projections assessed by the US

National Research Council[Ref] suggest

possible sea level rise over the 21st century

of between 56 cm and 2 m.

The predicted upper limit of sea level rise remains highly uncertain, due to the incomplete

understanding of fast ice streams and glacier collapse that are major contributors of ice

delivery to the sea and sea level rise (See Nature 461, 971-975, 2009).

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-25-320.jpg)

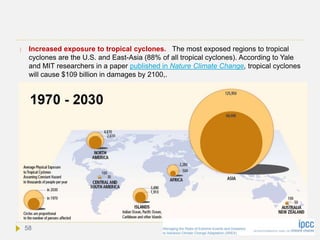

![Tropical cyclones

The intensity of Atlantic hurricanes is expected to increase as the ocean warms. More

heat means more energy to drive atmospheric circulations, evaporation and ocean-air

interactions. Although there have been dramatic improvements in predicting the

trajectory of tropical cyclones, the largest uncertainty exists in the prediction of tropical

cyclone intensity. The frequency of category 4 and 5 tropical cyclones over the 21st

century is expected to increase, the largest increase projected to occur in the Western

Atlantic, North of 20 degrees[Science 327, 454–458 (2010)]. A doubling of atmospheric CO2 may

increase the frequency of the most intense cyclones [J. Clim. 17, 3477 (2004)].

On the other hand, there is evidence that the strong cyclones cause a large amount

of ocean mixingRef, pumping heat from the surface down into the oceanic interior,

which is then redistributed over the globe, particularly through upwelling of the heat in

the equatorial Eastern Pacific, where El Niño originates. This may turn the globe into a

permanent El Niño condition[Ref], which will favor global warming in a closed positive

feedback loop.

In combination with sea level rise and tides, storm surges may cause more floods.

Moreover, climate simulations indicate that, as ice sheets release ice more and more

rapidly in ice streams and hence cool the ocean at high latitude, a point will be

reached when the high latitude ocean surface cools while low latitudes surfaces are

warming. Larger temperature contrast between low and high latitudes will induce

more powerful storms.[Ref]

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-43-320.jpg)

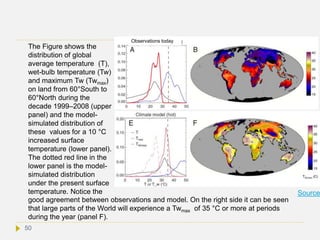

![Is the World inhabitable with a 10 °C rise in

average global temperature?

The human body at rest cannot survive in an ambient sustained wet bulb temperature

(Tw) ≥35°C. The highest Tw (Twmax) anywhere on Earth today is ~30 °C and the most-

common Twmax is 26–27 °C.[Ref] About 58% of the world’s population in 2005 resided in

regions where Twmax ≥ 26 °C. A recent climate model simulation study reported that a

global average temperature rise of 5 °C would result in a Twmax > 35 °C in some

locations. [Ref] For an 8.5 °C increase the most-common value of Twmax would be 35 °C

, which is incompatible with human life. With a 10 °C rise, many regions would

experience a Tw = 35 °C at a particular time each year, even in Siberia (see next

slide). It looks therefore that most of the World would be practically inhabitable

in a 10 °C warmer climate. At this temperature grain and agricultural production

would suffer very much or be destroyed, causing a food crisis. Humans could air-

condition their houses but deployment this over the World will be economically and

energetically extremely demanding and a power failure would be life threatening.

People working outside cannot work in air-conditioned environments and these would

rapidly develop hyperthermia. Poorer countries, which are located in tropical and

subtropical regions, will be hit the most.

During the PETM and EECO average global surface temperature rose 7-14 °C, which

is comparable to the study mentioned above. The question is then: How life could

have adapted to that hothouse? Humans have a body temperature of 37 °C but

many other mammals have a 2 °C and birds a 5 °C warmer body temperature[Ref] [Ref].

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-47-320.jpg)

![Non-human mammals and birds therefore may be more heat-tolerant than humans.

Just before the onset of the PETM mammals were small-sized (average = 1 kg)[Ref] [Ref]

[Ref]). This may have allowed their survival at that time, as small body mass is better

adapted to high temperatures (higher surface/mass ratio allowing better cooling).

Bioevolution during the PETM occurred over a time span of 20,000 years. In contrast,

anthropogenic warming extends over a few centuries, too short for a significant

evolutionary adaptation in heat tolerance.

But is this a realistic scenario? RCP8.5 is considered by IPCC as a worst case

scenario maintained up to 2300. If this scenario becomes reality, humans will have

made the World ~5-10 °C warmer by then. Atmospheric concentration would have

risen to ~7 x preindustrial. If fossil fuel burning would further increase, we would be

on the way to a 10 °C rise. However, it looks highly unlikely that humans would not

reduce greenhouse gas emissions as soon as the impacts of climate change become

frightening, which is definitely earlier than 2300. Nonetheless, the temperatures

reached at that time would decrease only very slowly, even under strong reductions or

complete elimination of CO2 emissions. Temperature might even increase temporarily

due to an abrupt reduction of short-lived aerosol emissions and, hence, of aerosol

negative forcing – see IPCC AR5 Ch. 12). Heat stored in the ocean will be released at

an even slower rate. Thus, we would be forced to live in a World with climate

disasters in many regions for many centuries.

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-48-320.jpg)

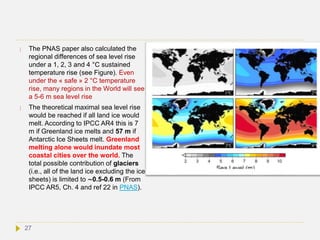

![ Can a 10 °C rise be reached if we burn all fossil energy? Since it takes

more than 1000 years for emitted CO2 to be removed, the cumulative amount of

emitted CO2 determines future climate. The amount of fossil fuels still available

ranges between 7,300-15,000 gigatonnes carbon equivalent. James Hansen

calculated[Ref] that burning this amount would increase Earth’s average surface

temperature with 16°C. It would make the World practically inhabitable.

49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-49-320.jpg)

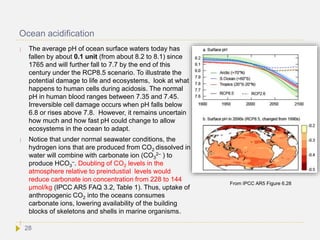

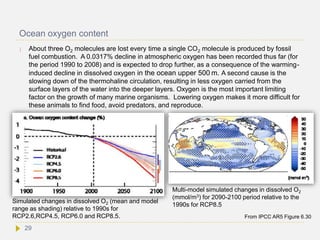

![Ecosystems[Ref]

In terrestrial ecosystems, the earlier timing of spring events, and poleward and upward

shifts in plant and animal range, have been linked with high confidence to recent

warming. Future climate change is expected to particularly affect certain ecosystems,

including tundra, mangroves, and coral reefs. It is expected that most ecosystems will

be affected by higher atmospheric CO2 levels, combined with higher global

temperatures. Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the extinction of

many species and reduce ecosystems diversity. Since ecosystems provide many

goods and services to humans and other living systems in a mutually dependent

manner, the consequences of ecosystem losses may become a very serious problem.

The current rate of ocean acidification is many times faster than at least the past 300

million years, which included four mass extinctions that involved rising ocean acidity,

such as the Permian mass extinction, which killed 95% of marine species. By the end

of the century, acidity changes would match that of the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal

Maximum (see slides on palaeoclimate), which occurred over 5000 years and killed

35–50% of benthic foraminifera[Ref] . It has been shown that corals, coccolithophore

algae, coralline algae, foraminifera, shellfish and pteropods experience reduced

calcification when exposed to elevated CO2 in the oceans. [Ref]

Warming of the surface ocean, combined with ocean acidification and reduction

in ocean oxygen concentration will have potentially nonlinear multiplicative impacts

on biodiversity and ecosystems and each may increase the vulnerability of ocean

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-53-320.jpg)

![systems, triggering an extreme impact. In the upper 500 m of the oceans oxygen

levels range between 50 and 300 mmol/m3, with levels highest at higher latitudes.

[Ref] Many marine organisms cannot survive under hypoxic conditions (oxygen

between 60 to 120 mmol/m3 depending on the species).[Ref] [Ref] Multiple studies

reported an impressive increase in the number of hypoxic ocean zones and their

extension, severity, and duration.[Ref] There are several examples in palaeoclimate

records that extreme ocean hypoxia led to the loss of 90% of marine animal taxa.[Ref]

The slowing down of the ocean’s circulation also results in fewer nutrients from the

deep layers into the ocean surface, which endangers oxygen-producing phytoplankton

that live in the ocean surface. Phytoplankton organisms produce half of the

world’s oxygen output (the other half is produced by plants on land). Hence, with

decreasing numbers of these oxygen producers, the level of oxygen in the ocean is

bound to decline further, entailing dramatic shortages in food supply.

As reported by the IPCC AR5 WG1 chapt. 12, models consistently predict an increase

in dry season length, and a 70% reduction in the areal extent of the rainforest by

the end of the 21st century under a worst case scenario. If the dry season becomes

too long, wildfires combined with human-caused fire ignition, can undermine the

forest’s resiliency. Fire and deforestation could act as a trigger to abruptly and

irreversibly change the forest ecosystem. Forests purify our air, improve water

quality, keep soils intact, provide us with food, wood products and medicines, protect

54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-54-320.jpg)

![Socio-economic consequences

Water and food supply:

Ocean warming, oxygen depletion, and acidification will result in reduction in primary

productivity of living species and, hence, in ocean goods and services for humans.

More floods will destroy more crops. Less water means less agriculture, food and

income. Crop yield will be decreased in drier areas.

The Himalayan glaciers provide water for drinking, irrigation, and other uses for about

1.5 billion people. Since most glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region are

retreating, the concern has been raised that over time the region's water supply may

be threatened. However, recent studies show that at lower elevations, glacial retreat is

unlikely to cause significant changes in water availability over the next several

decades. Other factors, such as groundwater depletion and increasing water use by

human activity could have a greater impact than the decrease of glacier water. On the

other hand, higher elevation areas could experience less water flow in some rivers if

current rates of glacier retreat continue, but shifts in rain and snow due to climate

change will likely have a greater impact on regional water supplies[Ref] . Whatever the

reason, climate change may likely threaten water supply and consequently food

supply.

Glacier recession reduces the buffering role of glaciers, hence inducing more floods

during the rainy season and more water shortages during the dry season.

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-56-320.jpg)

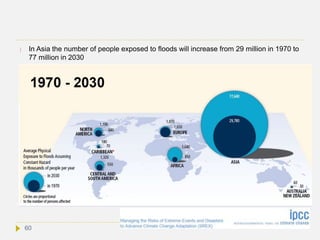

![ Increased exposure to floods.

An increase in the frequency or intensity of floods would be catastrophic in many low-

lying places around the World. Asian countries are particularly at risk, as low-lying

areas (like river deltas and small islands) are densely populated. In Bangladesh

alone, over 17 million people live at an elevation of less than 1 m above sea level, and

millions more inhabit the flat banks of the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers. Another

consideration is that poorer countries like Bangladesh do not have the financial

resources to relocate their citizens to lower risk areas, nor are they able to create

protective barriers. Read more

The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development announced the 10

cities most vulnerable to flooding. Six are in Asia: Mumbai, Shanghai, Ho Chi Minh

City, Calcutta, Osaka, and Guangzhou. The other four are in the United States: New

York City, Miami, Alexandria, and New Orleans. All are coastal, low-lying, and

densely populated[12].

Floodwaters can contaminate drinking water, and sea level rise can lead to the

contamination of private wells, with local catastrophic results.

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-59-320.jpg)

![ Environmental refugees:

There are currently between 25-30 million refugees worldwide as a consequence of

climate events, and their numbers are expected to rise to 200 million by

2100.[14]Unlike traditional refugees, environmental refugees are not recognized by the

Geneva Convention or the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR),

and therefore do not have the same legal status in the international community. Most

threatened are people in developing countries - in particular, people in low-lying

regions, on small islands, and arid regions that suffer from drought across North

Africa, farm regions dependent on river water from glacier and snow melt, and regions

of Southeast Asia facing changes in monsoon patterns. These countries have the

least economical power to adapt to climate change.

Most international statements on human rights in relation to climate change have

emphasized the potential adverse impacts of climate change on the human rights to

life, health, food, water, housing, development, and self-determination.[13] These rights

are enumerated in the UN conventions of international human rights law, though not

all UN members or UNFCCC parties have signed these conventions.

66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-66-320.jpg)

![ Worsening of human conflicts.

The impact of climate change will make

the poorest communities across the

world poorer. Many of them experience

conflict and instability, on top of poverty,

which exposes them to a dual risk. The

impact of climate change may entail

more violent conflict, which in turn

counteracts governments and people to

adapt to climate change. Thus, climate

change and violent conflict create a

potential vicious circle of destruction, if

not properly cared of by the international

community.

International peacebuilding NGO

International Alert named 46 countries

where climate change effects may

interact with economic, social, and

political forces to create a high risk of

violent conflict.[15]

1. Afghanistan

2. Algeria

3. Angola

4. Bangladesh

5. Bolivia

6. Bosnia & Herzegovina

7. Burma

8. Burundi

9. Central African Republic

10. Chad

11. Colombia

12. Congo

13. Côte d’Ivoire

14. Dem. Rep. Congo

15. Djibouti

16. Eritrea

17. Ethiopia

18. Ghana

19. Guinea

20. Guinea Bissau

21. Haiti

22. India

23. Indonesia

24. Iran

25. Iraq

26. Israel & Occupied

Territories

27. Jordan

28. Lebanon

29. Liberia

30. Nepal

31. Nigeria

32. Pakistan

33. Peru

34. Philippines

35. Rwanda

36. Senegal

37. Sierra Leone

38. Solomon Islands

39. Somalia

40. Somaliland

41. Sri Lanka

42. Sudan

43. Syria

44. Uganda

45. Uzbekistan

46. Zimbabwe

67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-67-320.jpg)

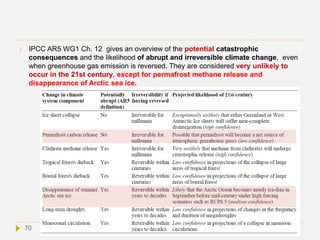

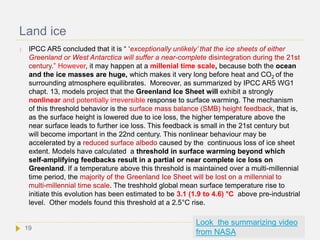

![Potentially abrupt and irreversible changes

(”tipping points”)

According to IPCC AR5 WG1 Chapter 12, abrupt climate change is defined as a

large-scale change in the climate system that develops over a few decades or less,

persists for at least a few decades, and causes substantial disruptions in human and

natural systems. Abrupt changes arise from nonlinearities within the climate system.

They are therefore inherently difficult to assess and their timing is difficult to predict.

Nevertheless, progress is being made on the basis of early warning signs for abrupt

climate change.

AR5 defines a perturbed climate state as irreversible (also known as a “tipping

point”), if the timescale of recovery from this state via natural processes is

significantly longer than the time it took for the climate system to reach this perturbed

state. According to this definition climate change resulting from CO2 emissions are

irreversible, due to the long residence time of the CO2 in the atmosphere and the

inertia of oceans to store the CO2 and the resulting warming (see next slides). A

tipping point is a point such that no additional forcing is required for large change and

impacts to occur.[8] If climate change reaches a state that causes serious disconfort to

humans, potential catastrophic situations emerge for centuties, and even millenia.

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climatechangeprediction-140804075719-phpapp02/85/Climate-change-prediction-69-320.jpg)