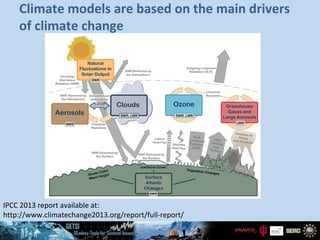

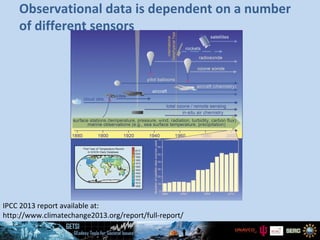

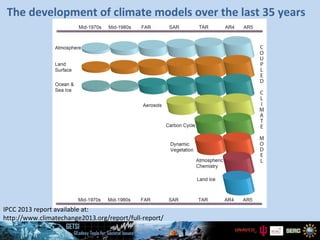

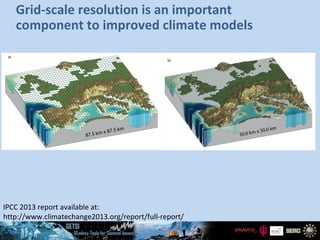

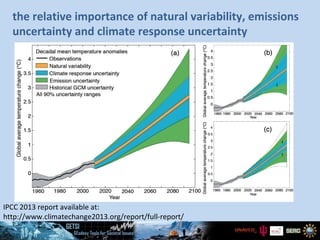

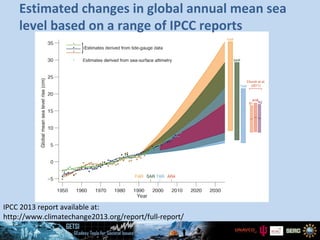

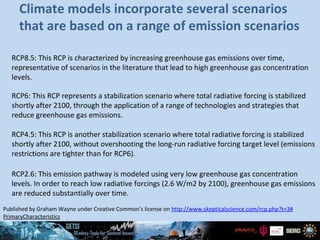

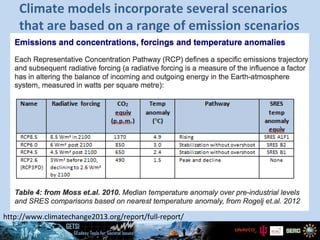

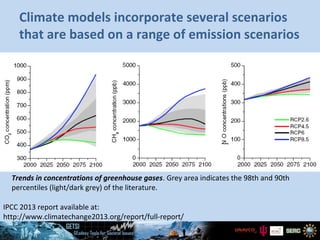

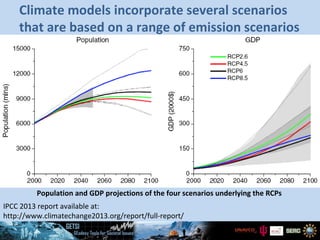

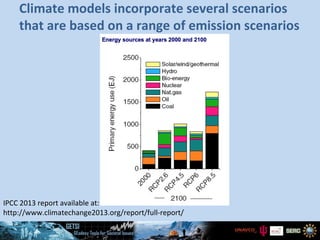

The document discusses key aspects of the 2013 IPCC report, including that climate models are based on the main drivers of climate change, observational data depends on different sensors, and grid-scale resolution is important for improved climate models. It also describes four emission scenarios (RCP8.5, RCP6, RCP4.5, and RCP2.6) that climate models incorporate to project a range of possible climate futures based on different levels of emissions.