The document summarizes the effects of climate change on different aspects of the biosphere, including land cover, marine life, forests, biodiversity, and humans. It discusses how land cover change affects surface albedo and evaporation. It also describes how ocean acidification impacts marine life by reducing the ability of some species to form shells and skeletons. Forests are threatened by diseases and wildfires fueled by climate change. Climate change endangers Arctic mammals that rely on sea ice. Humans face health risks from heat waves, storms, and changing disease patterns.

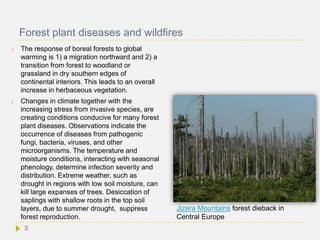

![ Alaska yellow-cedar decline is drought-related. A weak native pathogen causes red band

needle blight [Dothistroma septosporum]. An aggressive nonnative pathogen causes sudden

oak death [Phytophthora ramorum]). In California and Oregon, sudden oak death rates

abruptly increased and then subsided, the patterm being driven by heavy rains and extended

wet weather during warm periods. Infected trees suffer a reduced capacity to manage water,

but survive until high temperatures and extended dry periods overwhelm their vascular

capability, resulting in death. Two cycles of this pattern have been noted in California: 1998-

2001 and 2005 -2008 (Frankel 2007). The Bay Area experienced an all-time record for rainy

days in March 2006, followed in July by the longest string of hot weather ever recorded.

The Amazon rainforest. The strongest growth in the Amazon rainforest occurs during the dry

season as there is strong insolation, with water drawn from underground that stores the

previous wet season’s rainfall. In 2005, 1,900,000 km2 of rainforest experienced the worst

drought in 100 years.[59] Woods Hole Research Center showed that the forest could survive

only three years of drought.[61][62] Scientists at the Brazilian National Institute of Amazonian

Research argue that this drought response, coupled with the effects of deforestation by

humans, are pushing the rainforest towards a "tipping point" where it would start to die on a

centennial timescale. In the worst case the forest may turn into savanna or desert, with

catastrophic consequences for the World's climate. However, the IPCC AR5 report is less

pessimistic on this issue. In 2010 the Amazon rainforest experienced another severe drought

over 3,000,000 km2. In a typical year the Amazon forest absorbs 1.5 Gt of CO2; instead 8 Gt

less CO2 was captured.[64][65]

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/changesinthebiosphere-140804074421-phpapp01/85/Climate-change-Changes-in-the-biosphere-6-320.jpg)

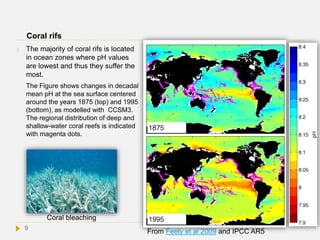

![Marine life

When CO2 dissolves in water (aq) the following dissociations and chemical aquilibria

exist:

About 90% of the dissolved inorganic carbon occurs as HCO3

–

and H+

ions. The latter

react with ocean CO3

2–

ions in an equilibrium:

The CO3

2–

ions make an equilibrium with Ca2+

ions and solid CaCO3 which is the

building block of shells and skeletons of marine species:

As a result, CO3

2–

concentrations decrease.

Many calcifying species such as planktonic coccolithophores, pteropods, clams,

oysters, mussels and corals may be adversely affected by a decreased capability to

produce their shells or skeletons. Fish and shellfish will also be negatively impacted.

Other consequences are depression of metabolic rates in jumbo squid,[7] depression of

immune responses of blue mussels,[8] and coral bleaching. On the basis of our present

understandings, the potential for environmental and economic risks is high (IPCC AR5:

Cooley et al., 2009).

Ocean acidification may also generate genome-wide changes in purple sea urchins.

When tested in culture under different CO2 levels, genetic changes occurred in genes

for biomineralization, lipid metabolism, and ion homeostasis, gene classes that build

skeletons and interact in pH regulation[Ref] .

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/changesinthebiosphere-140804074421-phpapp01/85/Climate-change-Changes-in-the-biosphere-8-320.jpg)

![Biodiversity

Terrestrial biodiversity tends to be highest near the equator,[2] which seems to be the result

of the warm climate and high primary productivity (growth of their biomass ).[3] Marine

biodiversity tends to be highest along coasts in the Western Pacific, where sea surface

temperature is highest and in the mid-latitudinal band in all oceans.[4 Not the climate itself

but rapid climate change has been associated in the past with biodiversity loss. At least 5

large and several smaller mass extinctions have occurred during the last 500 million years,

but biodiversity over long time periods has steadily expanded despite these massive losses.

Only 1%-3% of the species that have existed on Earth still exist today.[12]

At present, biodiversity is declining again but this is already going on from the beginning of

the Holocene, more than 10,000 years ago. It is thought to be caused primarily by human

impacts, particularly by habitat destruction from human-induced land use change. Thus,

biodiversity loss in not an Industial Era event alone, but there are indications that climate

change may accelerate loss of biodiversity. However, other factors that are human-related

play an even more important role, such as pollution.

From 1950 to 2011, human world population increased from 2.5 billion to >7 billion and is

predicted to reach a plateau of more than 9 billion during the 21st century.[162] It has been

claimed that the massive growth in the human population through the 20th century has had

more impact on biodiversity than any other single factor.[163][164] Whatever the causes,

biodiversity loss means loss of ‘ecosystem services’ to humans.

Biodiversity is a broad subject on its own, it is not further dealt with here but read more here

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/changesinthebiosphere-140804074421-phpapp01/85/Climate-change-Changes-in-the-biosphere-11-320.jpg)

![Economical impacts

Climate change is slowing down world economic output by 1.6 % a year and will lead

to a doubling of damage costs in the next two decades.

Read more here.

Global loss rose from a few billions in the 1980’ to above 200 billions per year (in

2010 US$). (from IPCC “Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to

Advance Climate Change Adaptation (SREX)”

Economic losses in percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (2001- 2006) are:

- 0.3% in low-income countries.

- 1% in middle income countries,

- 0.1% in developped countries,

- 1% in Small Island Developing States (up to 8 % in extreme case).

Most of the increase is due to increase in exposure (high confidence), but

a role of climate change has not been excluded.

During the exceptionally hot 2003 summer in France some nuclear power reactors

had to be temporarily shut down due to lack of cooling water.[Ref] Russia referred an

annual crop failure of ~25%, more than 1 million ha of burned areas, and ~$15 billion

(~1% GDP) of total economic loss.

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/changesinthebiosphere-140804074421-phpapp01/85/Climate-change-Changes-in-the-biosphere-16-320.jpg)

![Season creep

Observations indicate earlier arrival of spring-like temperatures and later arrival of

winter-like temperatures (season creep), although evidence is not robust enough to

distinguish the change from natural variability with high confidence. In Europe, arrival

of spring appears to have moved up by approximately one week in a recent 30 year

period.[9][10] Studies of plant phenology found advancement in spring in the range of 2–

3 days per decade, and 0.3–1.6 days per decade delay in autumn, over the past 30–

80 years.[11] Studies have suggested that changes in the season-determined

synchrony of biological events is disturbed by climate chang, as different species have

changed their seasonal timing to different degrees. For example, woodland birds feed

moth larvae to their young and produce the greatest number of chicks when caterpillar

number peaks. In warm years caterpillar are now most numerous before the nestlings

have hatched, which can result in starvation and decrease in population size. A large

phenological examination on 542 plant species in 21 European countries from 1971–

2000 showed that 78% of all leafing, flowering, and fruiting records advanced while

only 3% were significantly delayed.[10][30] However, more needs to be studied before

the overall impact of seasonal change on ecosystems can be estimated with high

confidence. Efforts are now being made to gather more data and implement them in

models[Ref].

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/changesinthebiosphere-140804074421-phpapp01/85/Climate-change-Changes-in-the-biosphere-17-320.jpg)