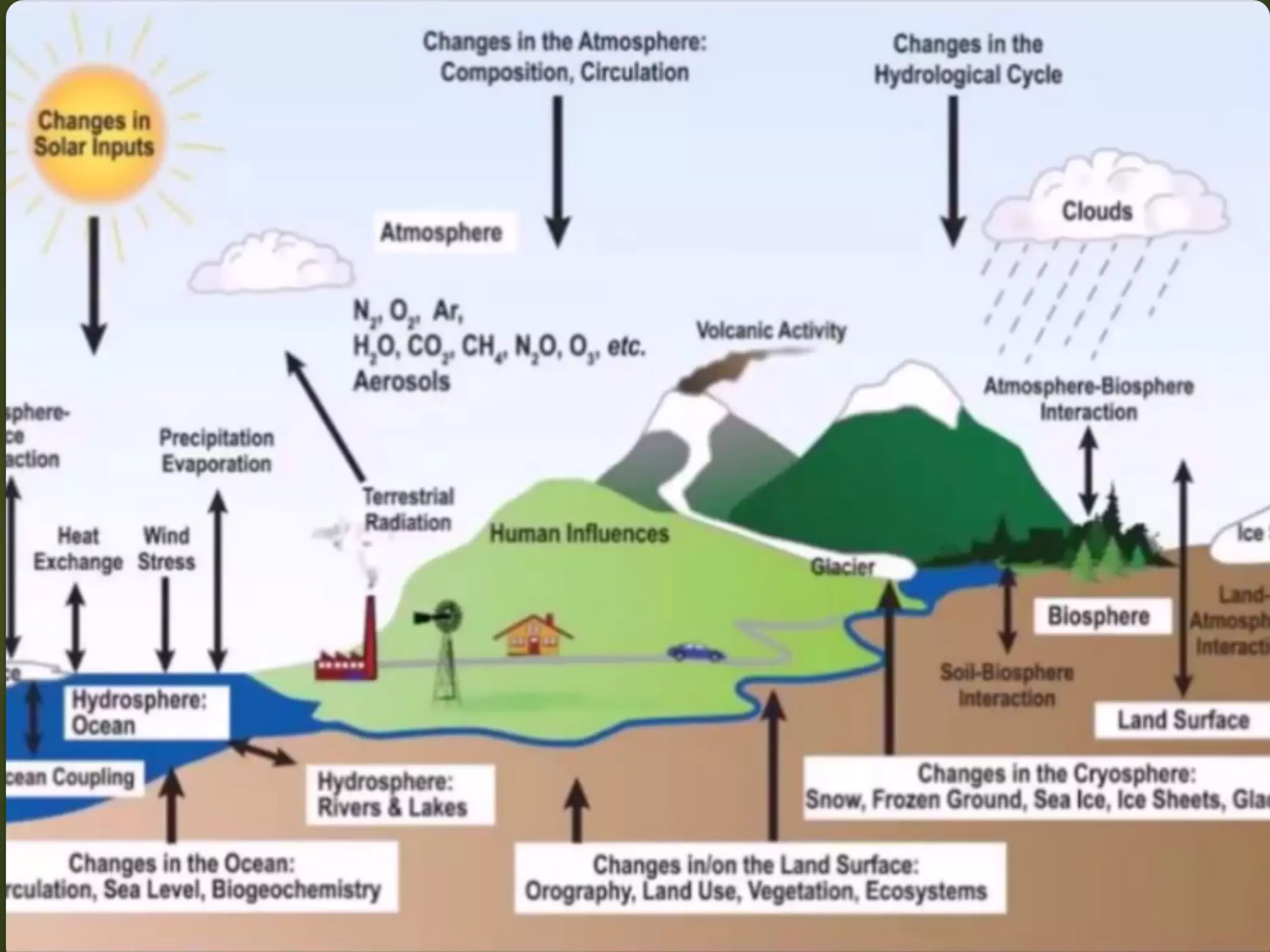

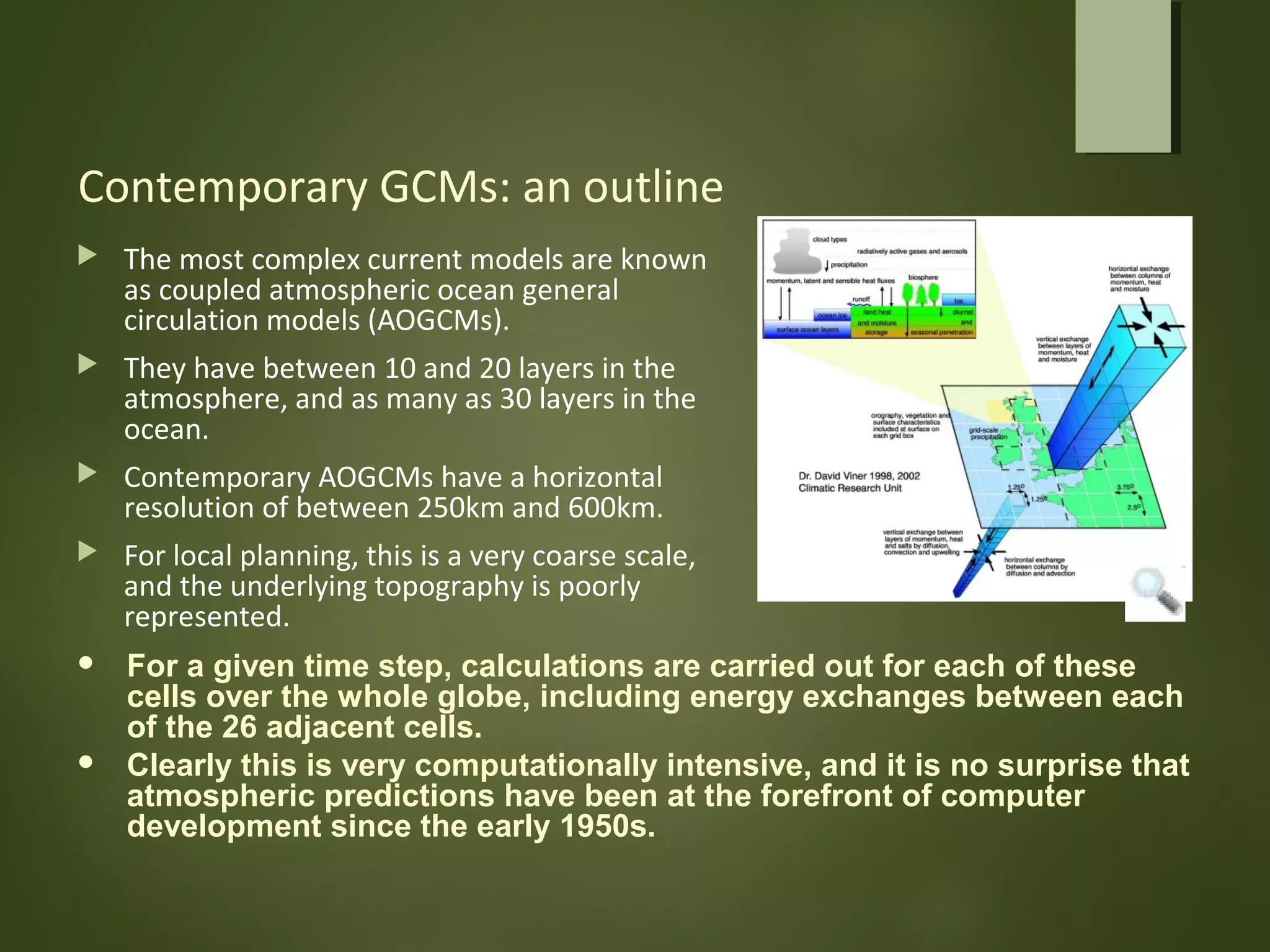

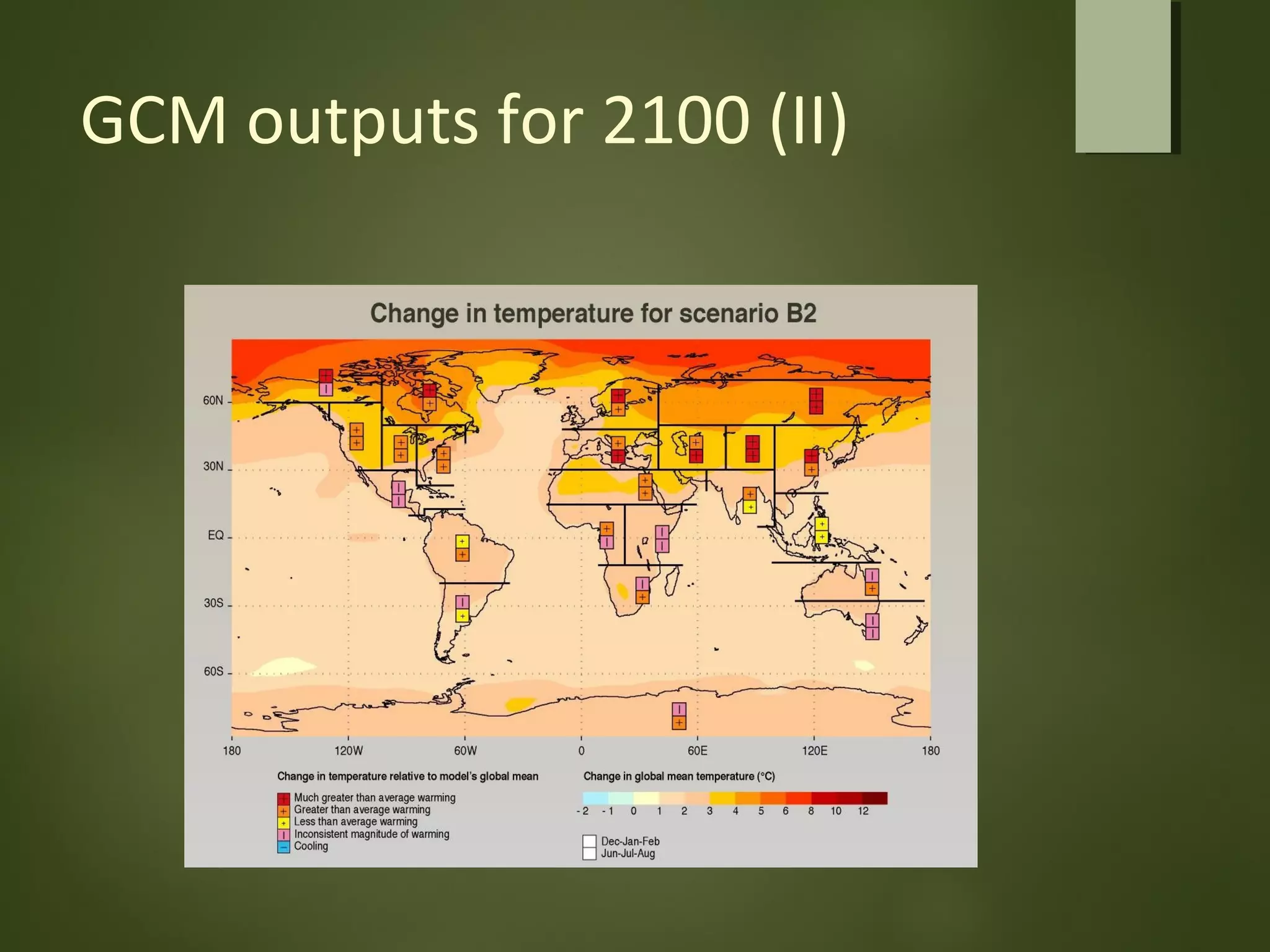

General circulation models (GCMs) are computer models that simulate the operation of the climate system. GCMs take into account factors like greenhouse gases, landforms, ocean currents, and their interactions. GCMs are used to both identify possible causes of climate change and predict future climate. Contemporary GCMs are complex, three-dimensional models with thousands of individual cells that simulate atmospheric and oceanic processes globally. GCMs are the best tools available for determining the potential impacts of climate change and informing conservation and policy responses.