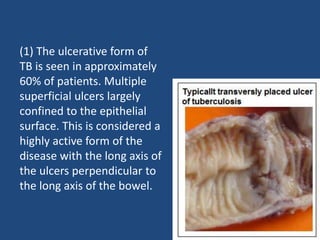

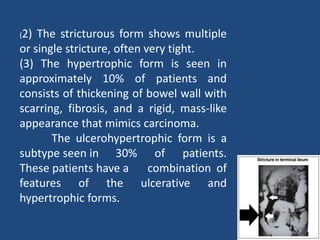

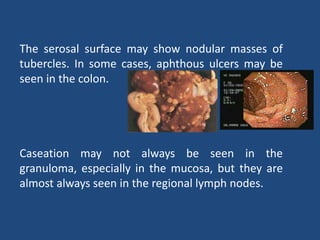

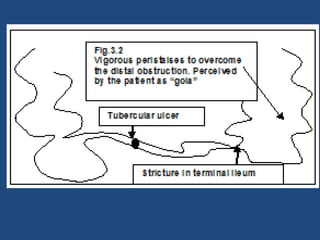

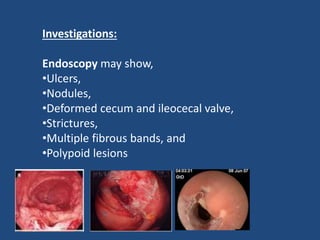

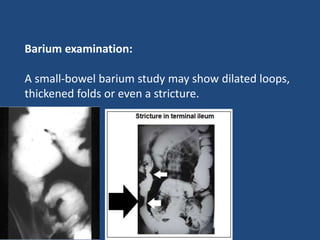

Abdominal tuberculosis (TB) is a significant health issue in the developing world, often associated with immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with HIV/AIDS. It primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, especially the ileocecal area, presenting with non-specific abdominal pain, weight loss, and complications such as intestinal obstruction. Diagnosis typically requires imaging studies and can involve empirical treatment; surgical intervention is necessary for symptomatic strictures.