The document discusses liver anatomy, injuries, and management approaches. It provides details on:

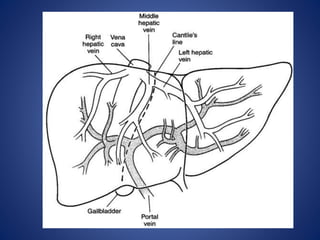

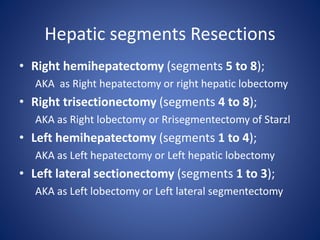

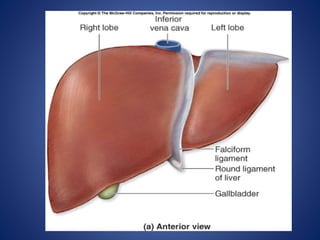

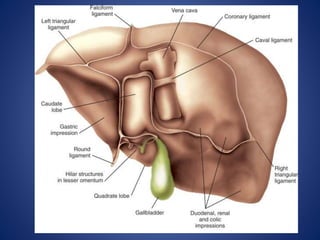

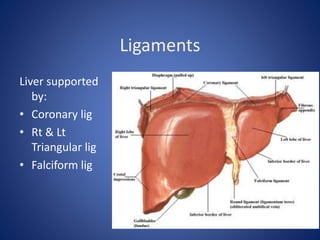

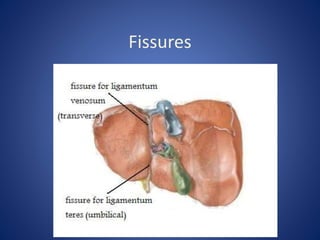

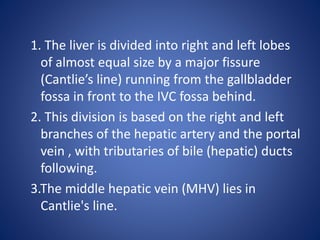

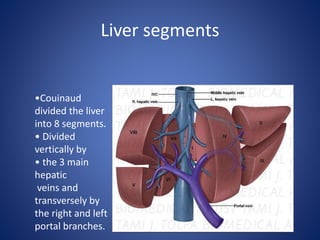

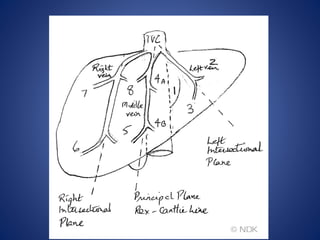

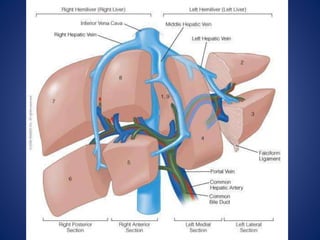

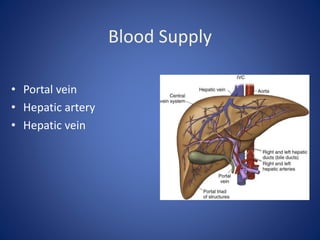

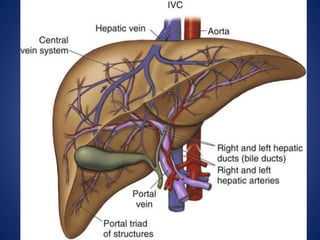

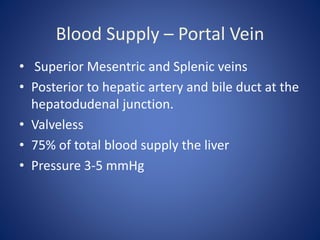

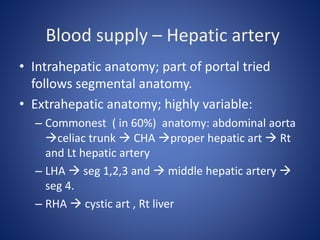

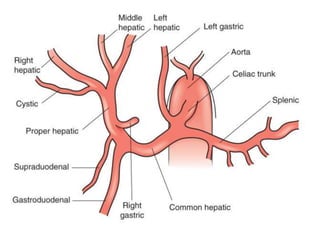

1) The surface anatomy and blood supply of the liver.

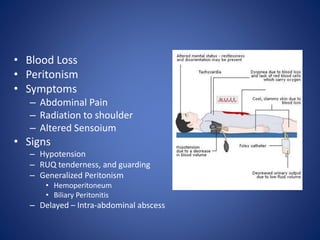

2) Common causes and presentations of liver injuries including blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, and associated injuries.

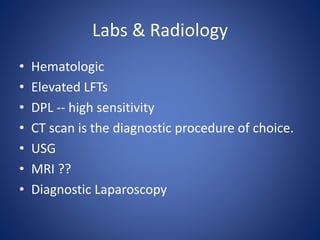

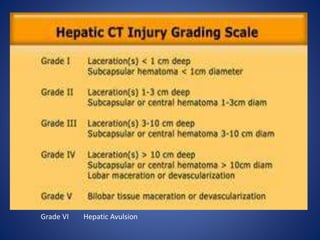

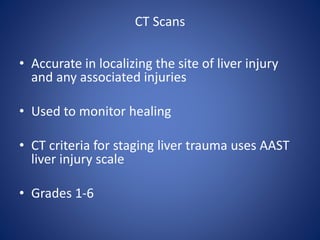

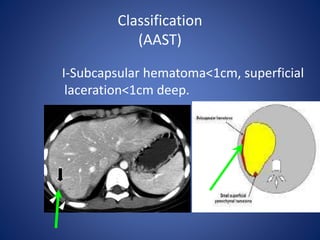

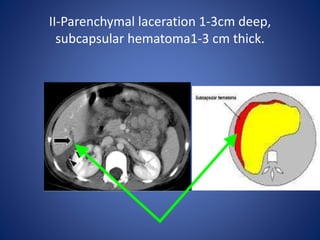

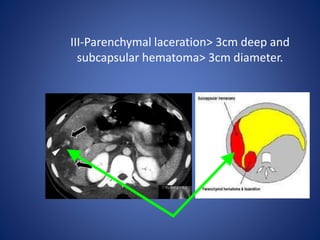

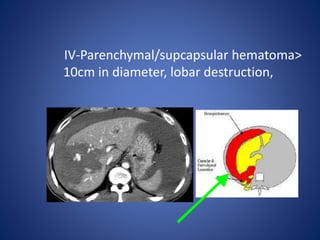

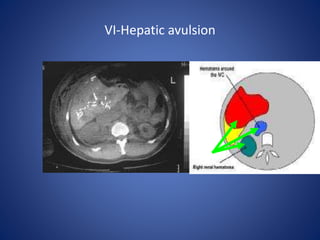

3) Classification systems for grading liver injuries based on CT imaging findings.

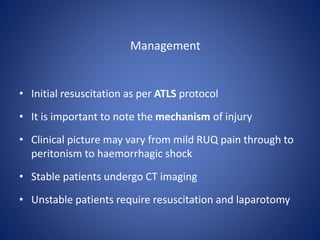

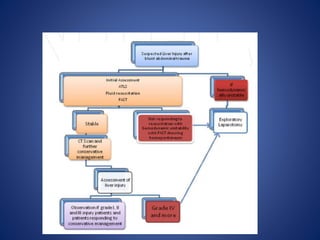

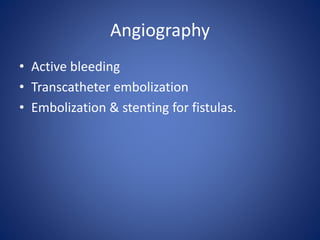

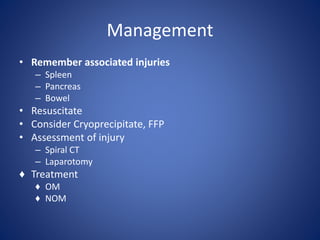

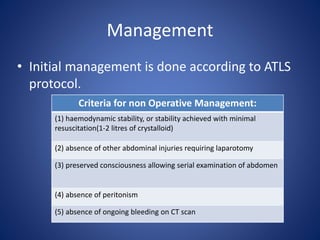

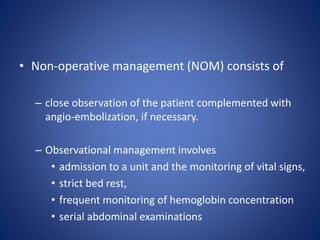

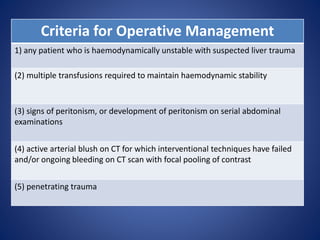

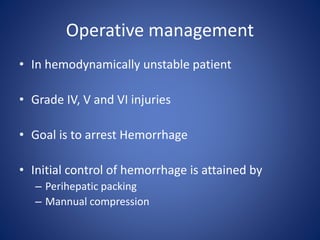

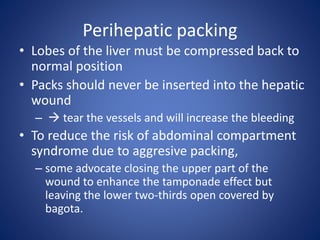

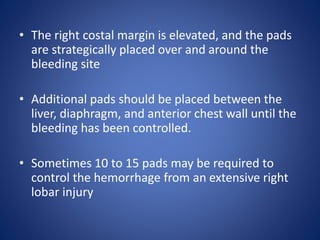

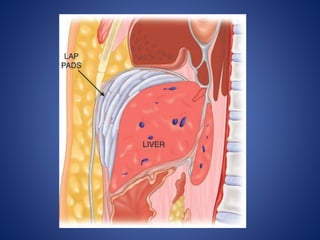

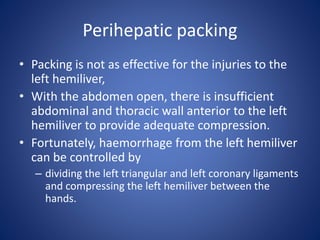

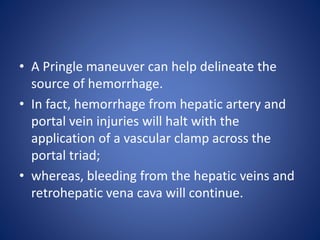

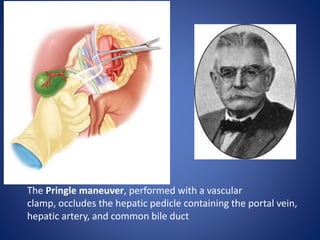

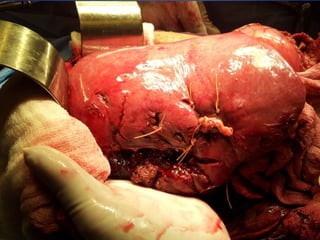

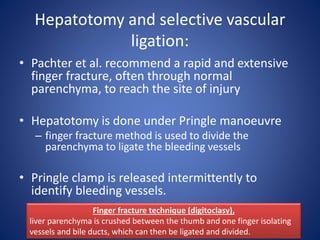

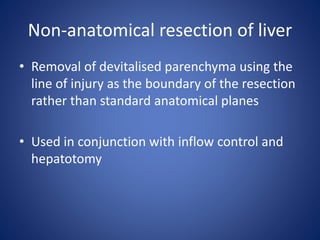

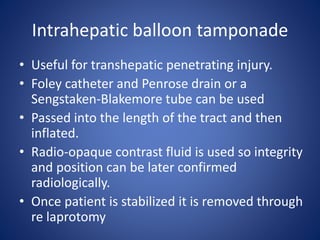

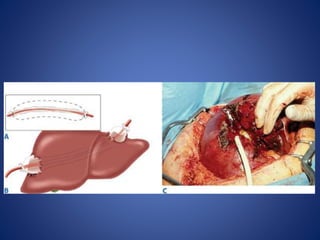

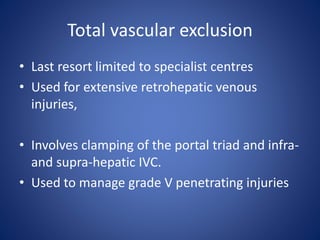

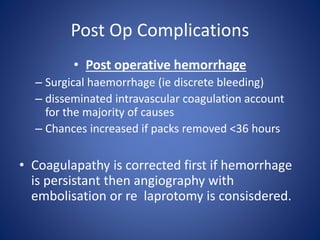

4) Treatment approaches including non-operative management with observation for lower grade injuries or angioembolization for bleeding, and operative management using packing, Pringle maneuver, and resection for higher grade or unstable injuries.

![Blood supply – Hepatic vein

• Rt hepatic vein Drain seg 5,6,7,8 vena

cava.

• Middle hepatic vein Drain seg 4,5,8

• Lt hepatic vein Drain seg 2,3

[ seg 1 drain by short hepatic vena cava]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/livertrauma-170928174656/85/Liver-trauma-20-320.jpg)