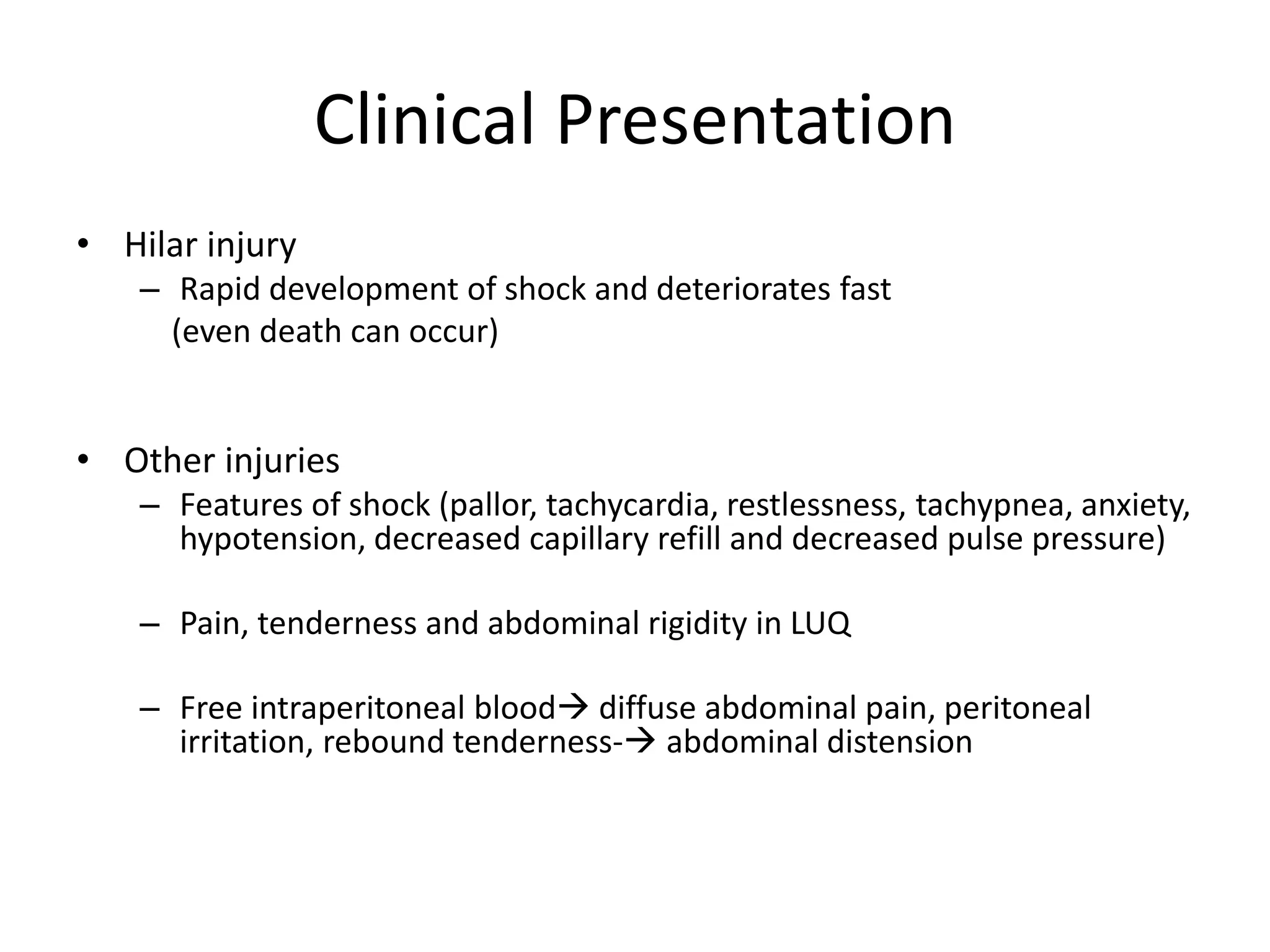

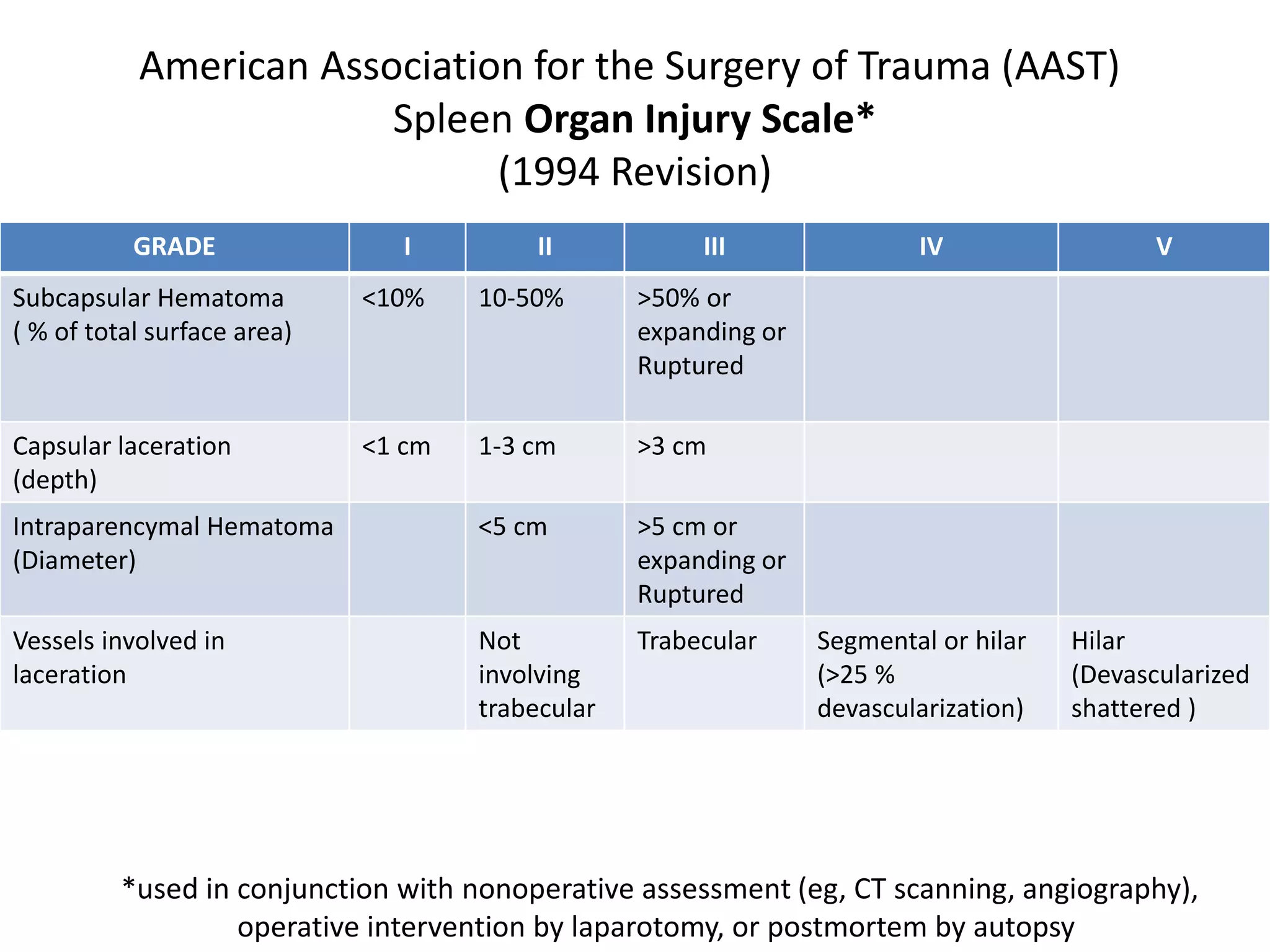

The document outlines the management and treatment of splenic injuries based on the Eastern Association for Surgery of Trauma (EAST) 2012 guidelines, emphasizing the evolution from routine surgical intervention to non-operative management for stable patients. It includes historical perspectives, surgical anatomy, causes of splenic injury, clinical presentation, diagnostic workup, and updated management recommendations, highlighting the value of computed tomography and interventional radiology. Additionally, it specifies recommendations regarding patient assessment, contrast imaging, and indications for surgery, while also identifying gaps in research for future inquiry.