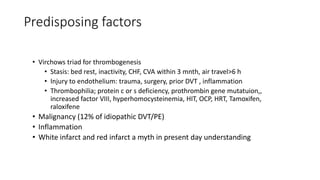

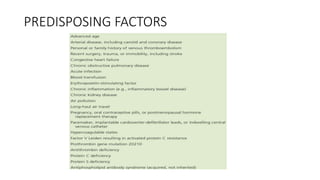

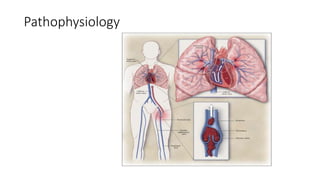

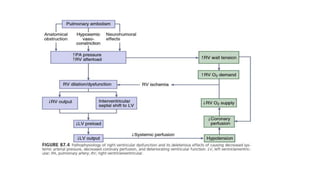

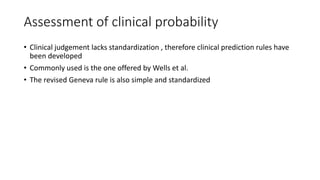

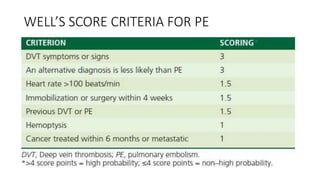

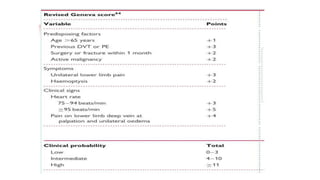

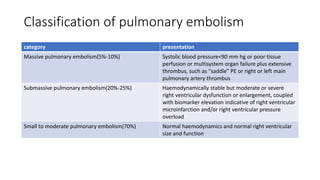

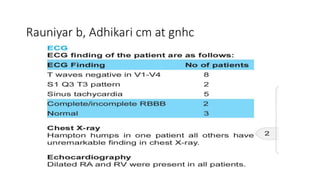

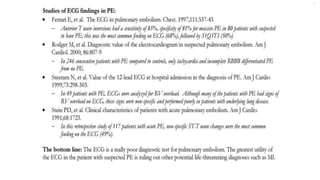

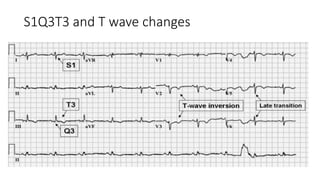

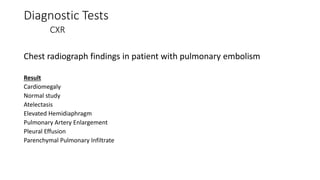

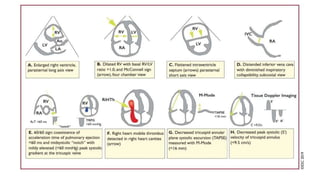

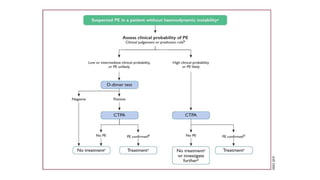

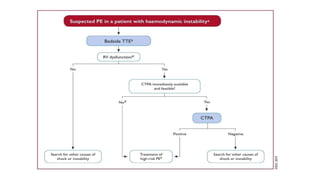

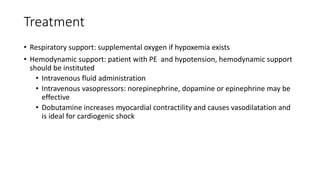

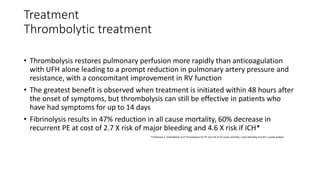

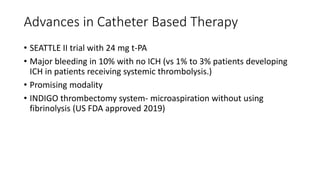

This document provides information on pulmonary embolism (PE). It defines PE as thrombosis originating in the venous system and embolizing to the pulmonary arterial circulation. PE contributes to 5-10% of hospital deaths. Risk factors include prolonged immobility, recent surgery or trauma, and inherited or acquired thrombophilias. Symptoms include dyspnea, chest pain, coughing up blood. Diagnostic tests include D-dimer, CT pulmonary angiogram, ventilation-perfusion scan, echocardiogram. Treatment involves anticoagulation with heparin or novel oral anticoagulants to prevent early death and recurrence, as well as thrombolysis for massive PE to restore pulmonary blood flow.

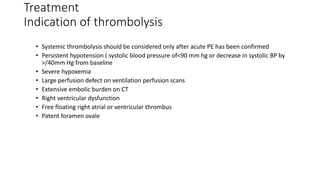

![Treatment

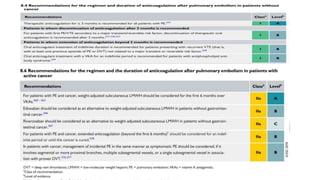

Initiation of anticoagulation therapy

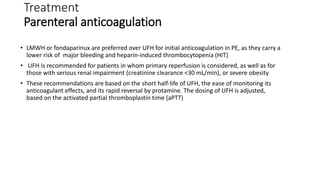

• Anticoagulation is recommended, with the objective of preventing both early death and

recurrent symptomatic or fatal VTE

• Consists of administering parenteral anticoagulation [unfractionated heparin (UFH), low

molecular weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux] over the first 5–10 days

• Parenteral heparin should overlap with the initiation of a vitamin K antagonist (VKA);

alternatively, it can be followed by administration of one of the new oral anticoagulants:

dabigatran or edoxaban. rivaroxaban or apixaban

• Oral treatment with one of these agents should be started directly or after a 1–2 day

administration of UFH, LMWH or fondaparinux

• In this latter case, acute-phase treatment consists of an increased dose of the oral

anticoagulant over the first 3 weeks (for rivaroxaban), or over the first 7 days (for apixaban)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asrafpresentation-220312012735/85/Pulmonary-Embolism-56-320.jpg)