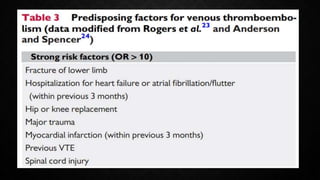

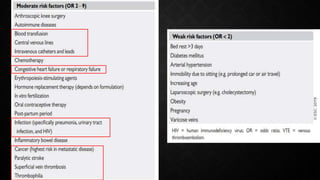

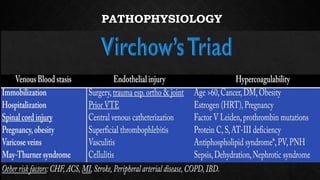

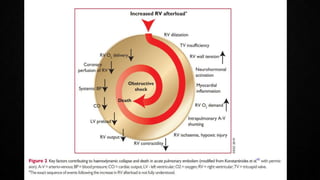

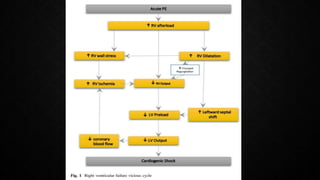

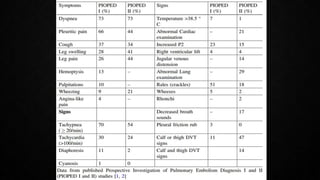

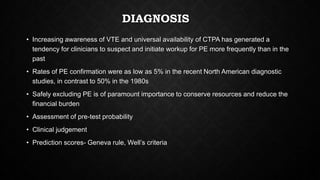

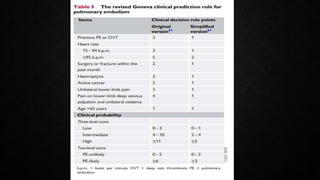

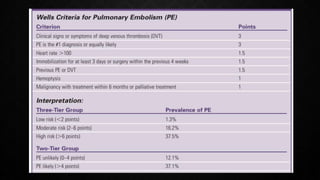

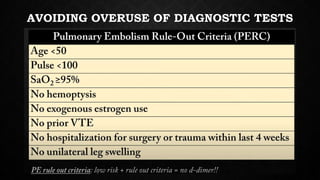

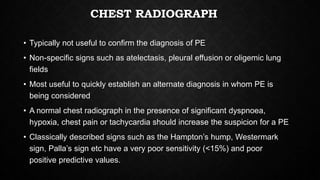

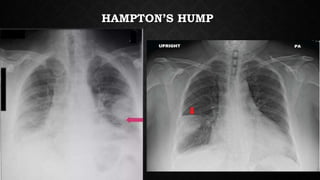

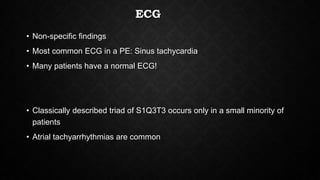

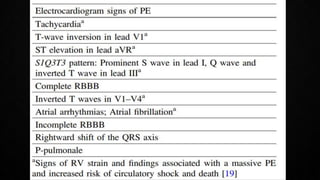

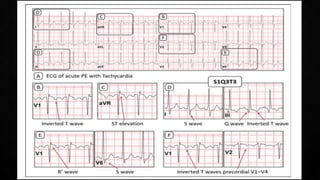

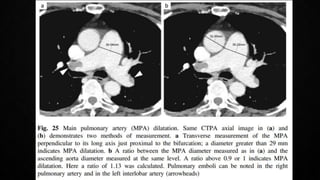

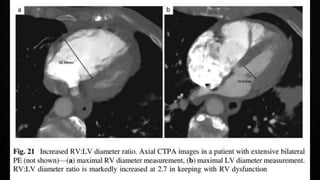

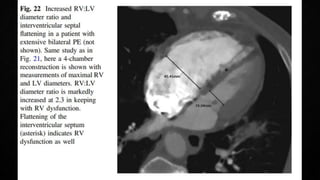

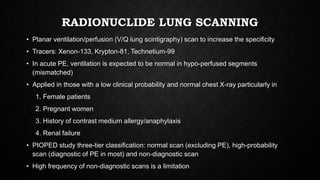

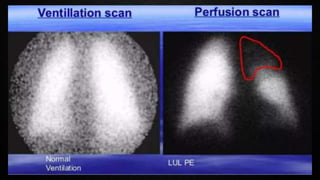

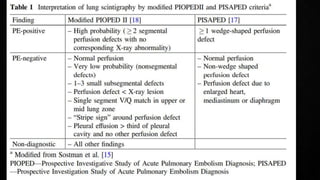

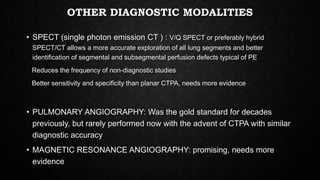

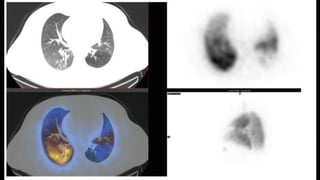

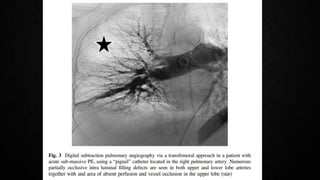

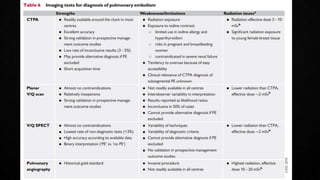

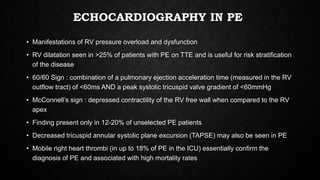

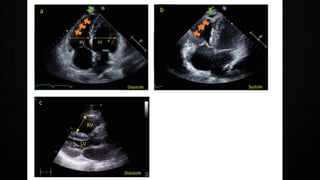

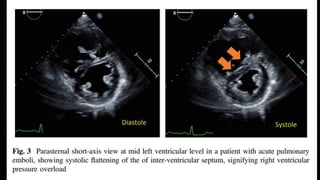

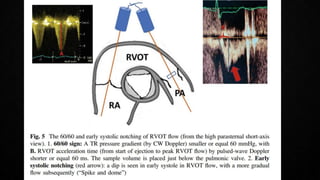

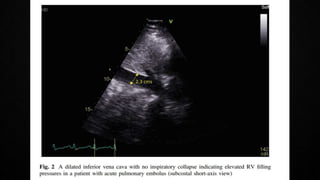

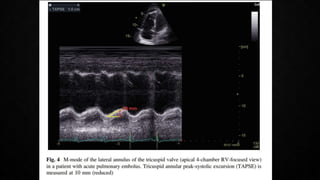

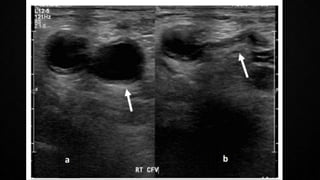

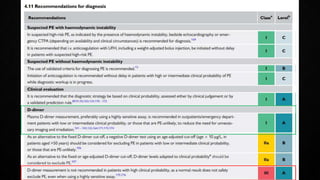

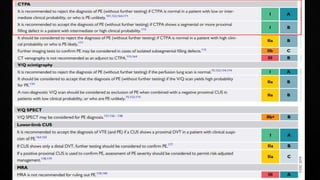

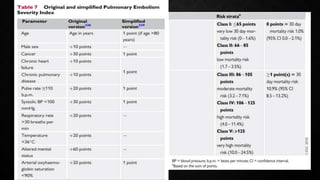

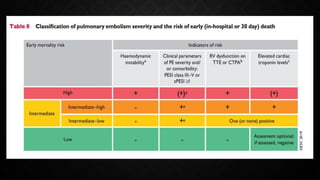

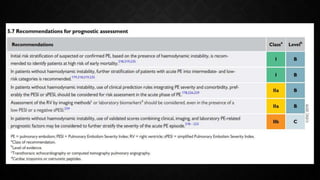

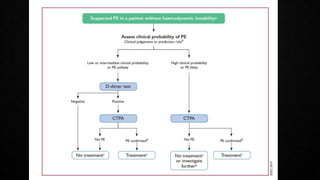

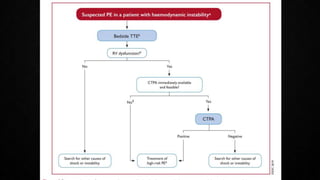

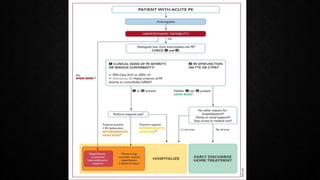

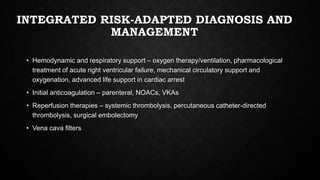

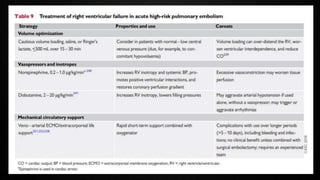

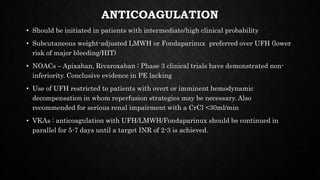

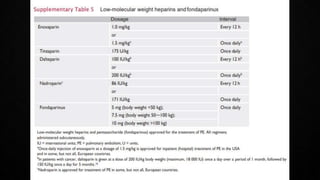

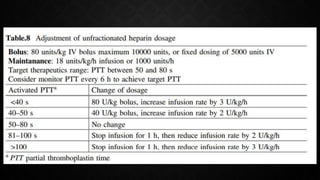

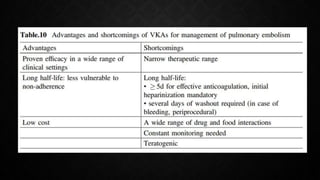

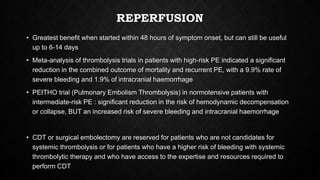

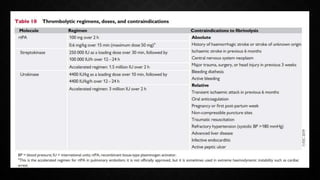

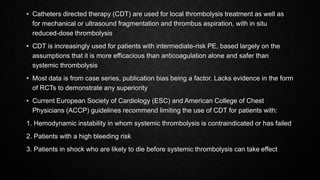

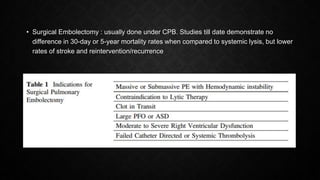

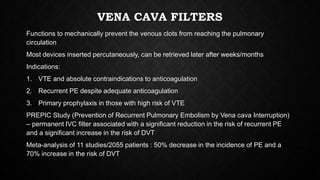

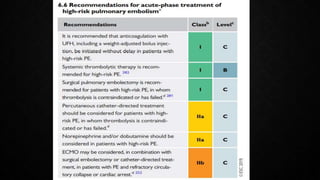

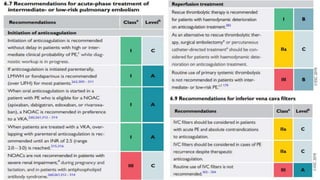

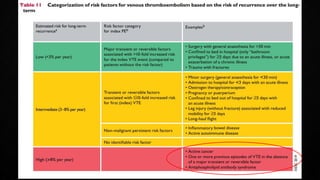

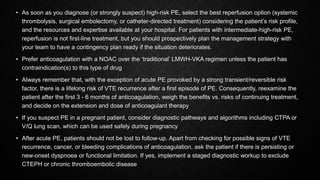

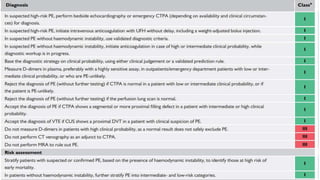

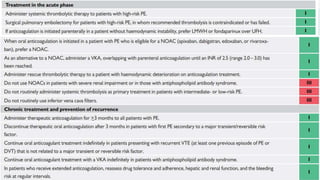

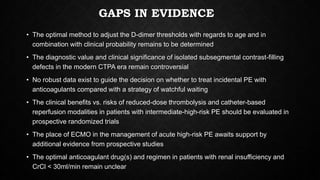

This document provides an overview of pulmonary embolism (PE), including its epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, assessment of severity and prognosis, treatment options, and special considerations. It discusses diagnostic tests and strategies like D-dimer testing, CT pulmonary angiography, echocardiography, and their appropriate use. Treatment options covered include anticoagulation, reperfusion therapies, and inferior vena cava filters. Key messages emphasize the importance of risk stratification to guide management, and selecting the best reperfusion option for high-risk PE based on patient risk profile and hospital resources.