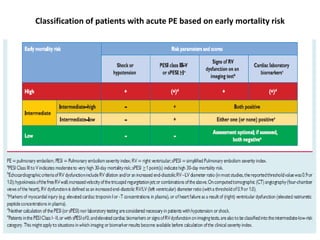

- Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage in the lung's arteries caused by blood clots that travel from deep veins, most often in the legs.

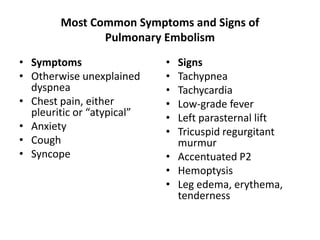

- Risk factors include recent surgery or trauma, cancer, older age, and genetic predispositions. Symptoms can range from mild to life-threatening depending on the size and location of the clots.

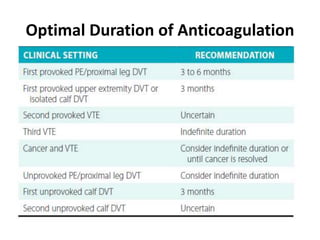

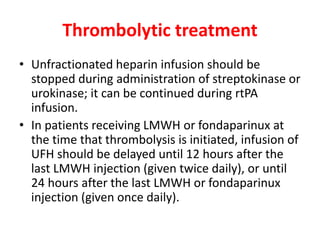

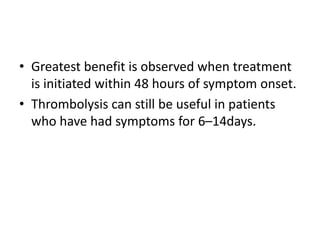

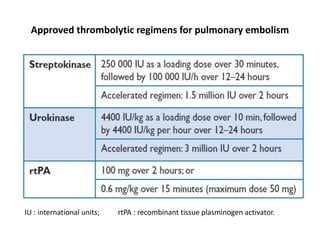

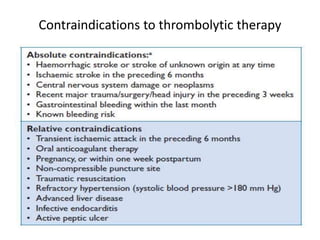

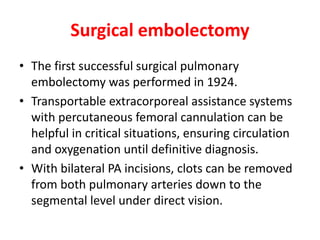

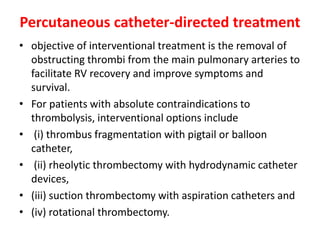

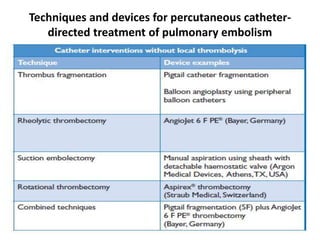

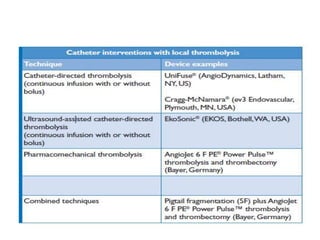

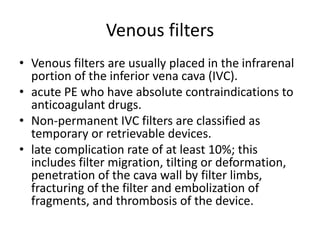

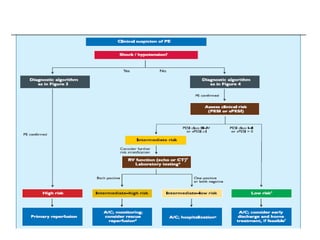

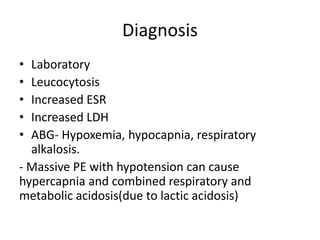

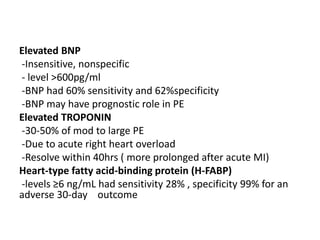

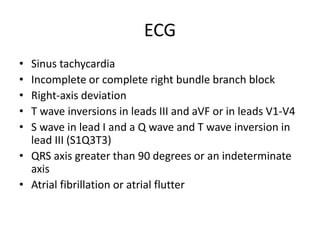

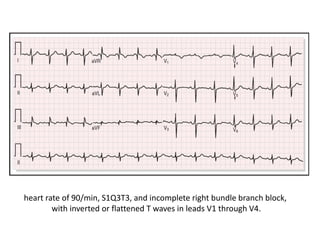

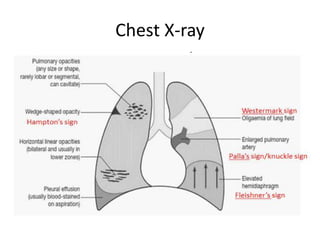

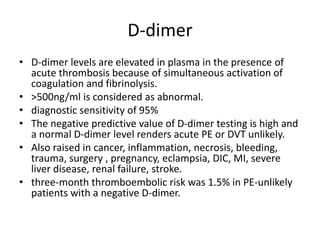

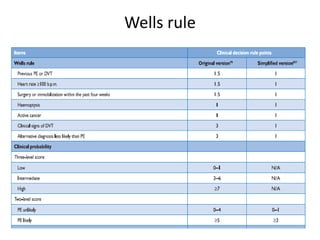

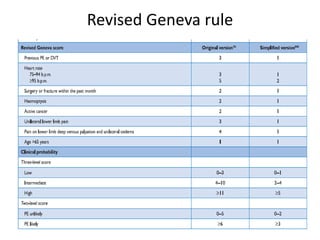

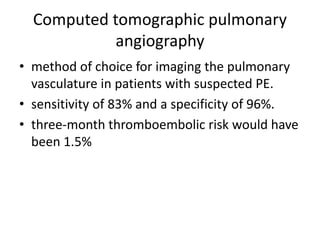

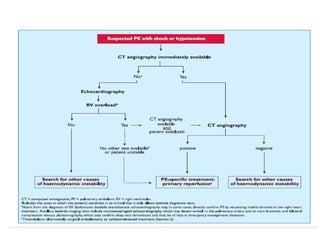

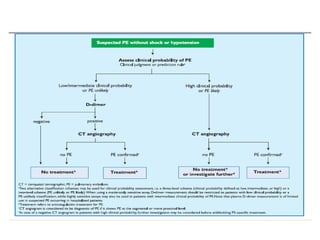

- Diagnosis involves blood tests, imaging like CT scans, ventilation-perfusion scans, or angiography. Treatment focuses on anticoagulation with blood thinners to prevent further clotting as well as supporting heart and lung function. For some patients, more aggressive options like thrombolysis or surgery may be considered.

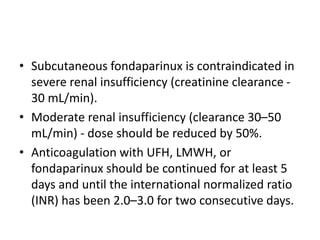

![Anticoagulation

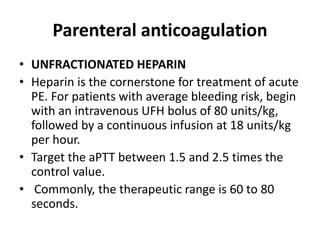

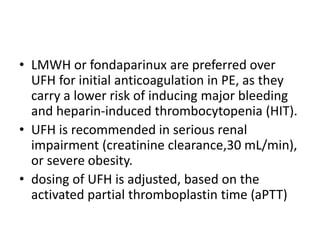

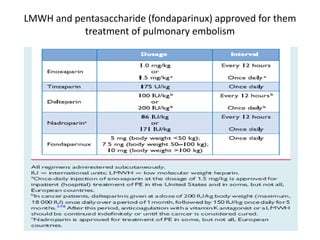

• acute-phase treatment consists of administering

parenteral anticoagulation [unfractionated heparin

(UFH), low molecular weight heparin(LMWH), or

fondaparinux] over the first 5–10 days.

• Parenteral heparin should overlap with the initiation of

a vitamin K antagonist (VKA); alternatively, it can be

followed by administration of one of the new oral

anticoagulants: dabigatran or edoxaban.

• If rivaroxaban or apixaban is given instead, oral

treatment with one of these agents should be started

directly or after a 1–2 day administration of UFH,

LMWH or fondaparinux.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pulmonaryembolism-211210151304/85/Pulmonary-embolism-38-320.jpg)