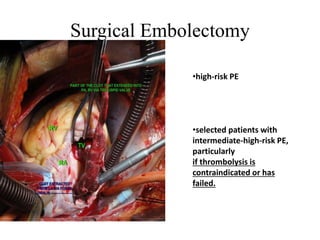

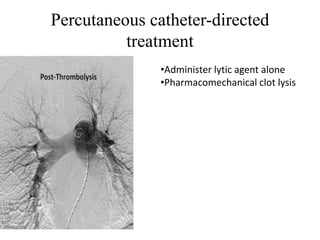

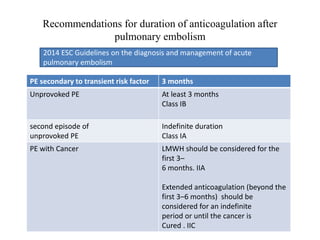

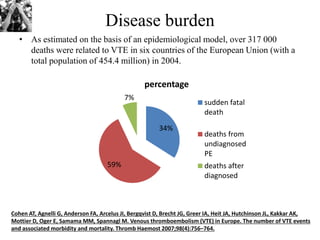

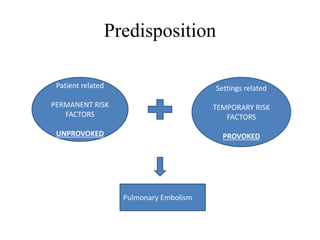

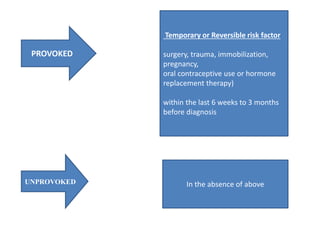

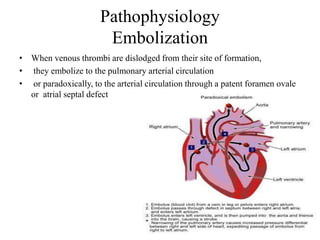

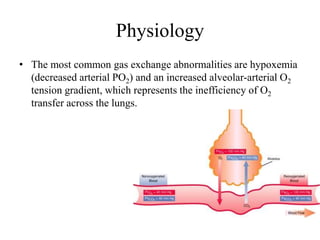

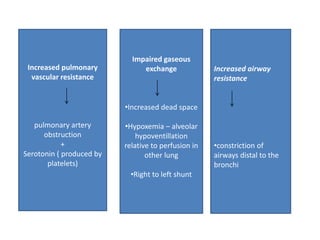

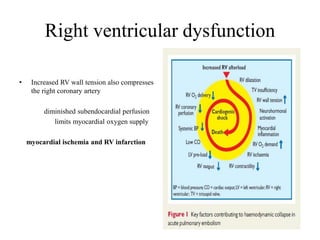

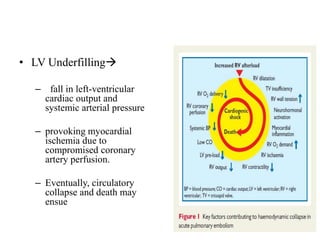

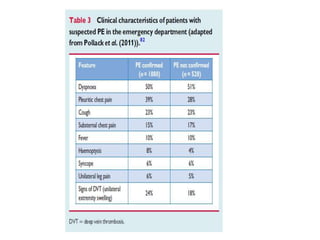

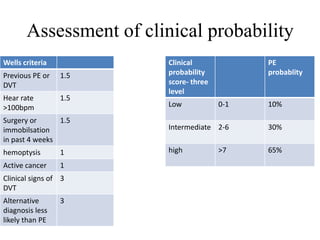

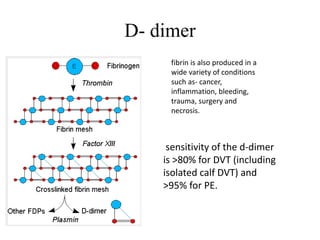

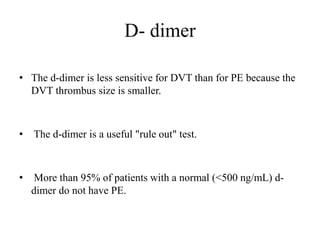

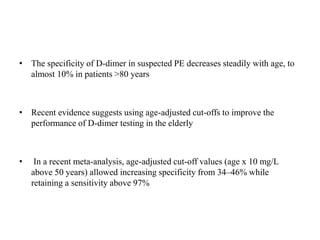

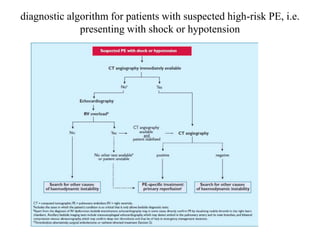

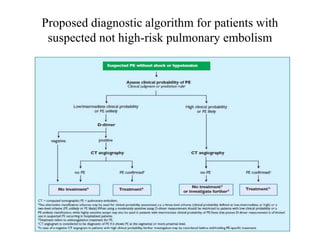

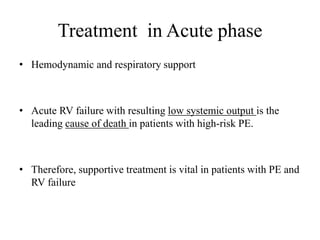

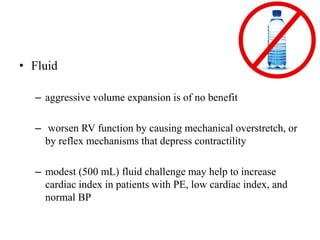

This document discusses pulmonary embolism (PE), including its epidemiology, disease burden, risk factors, pathophysiology, signs and symptoms, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment approaches. It notes that PE has an annual incidence of 100-200 per 100,000 people. Diagnostic evaluations discussed include assessment of clinical probability, D-dimer testing, CT pulmonary angiography, lung scintigraphy, and echocardiography. Treatment of acute PE involves hemodynamic support, anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux, and potentially thrombolysis for high-risk cases.

![Anticoagulation

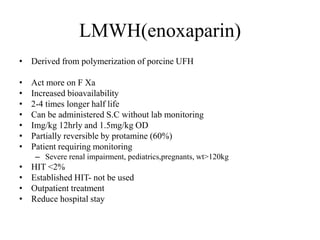

• In patients with acute PE, anticoagulation is recommended, with the

objective of preventing both early death and recurrent symptomatic or fatal

VTE

• The standard duration of anticoagulation should cover at least 3 months

• acute-phase treatment consists of administering parenteral anticoagulation

[unfractionated heparin (UFH), LMWH or fondaparinux] over the first 5–

10 days.

• Parenteral heparin should overlap with the initiation of a vitamin K

antagonist (VKA)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pe-180104202534/85/Pulmonary-embolism-45-320.jpg)