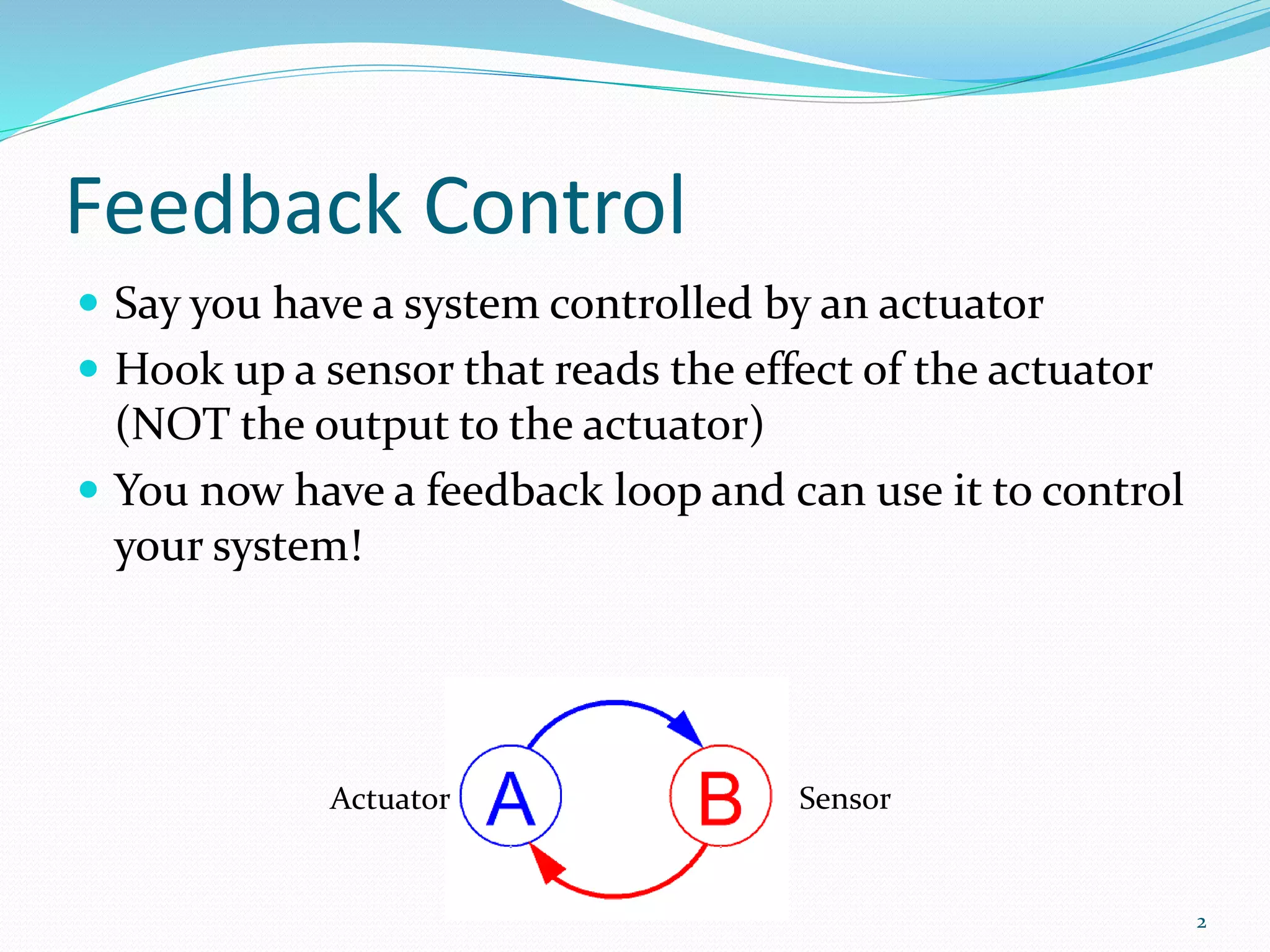

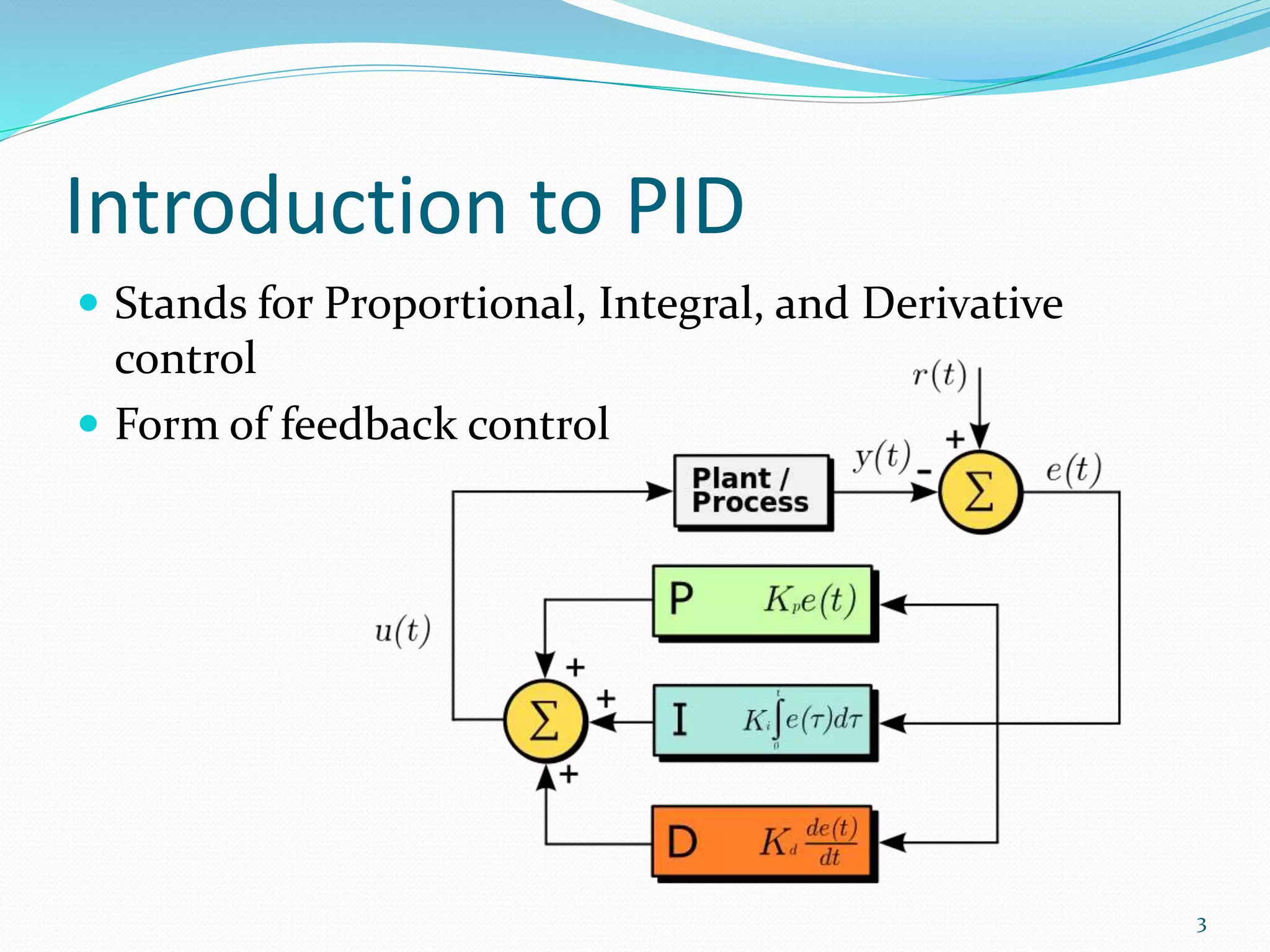

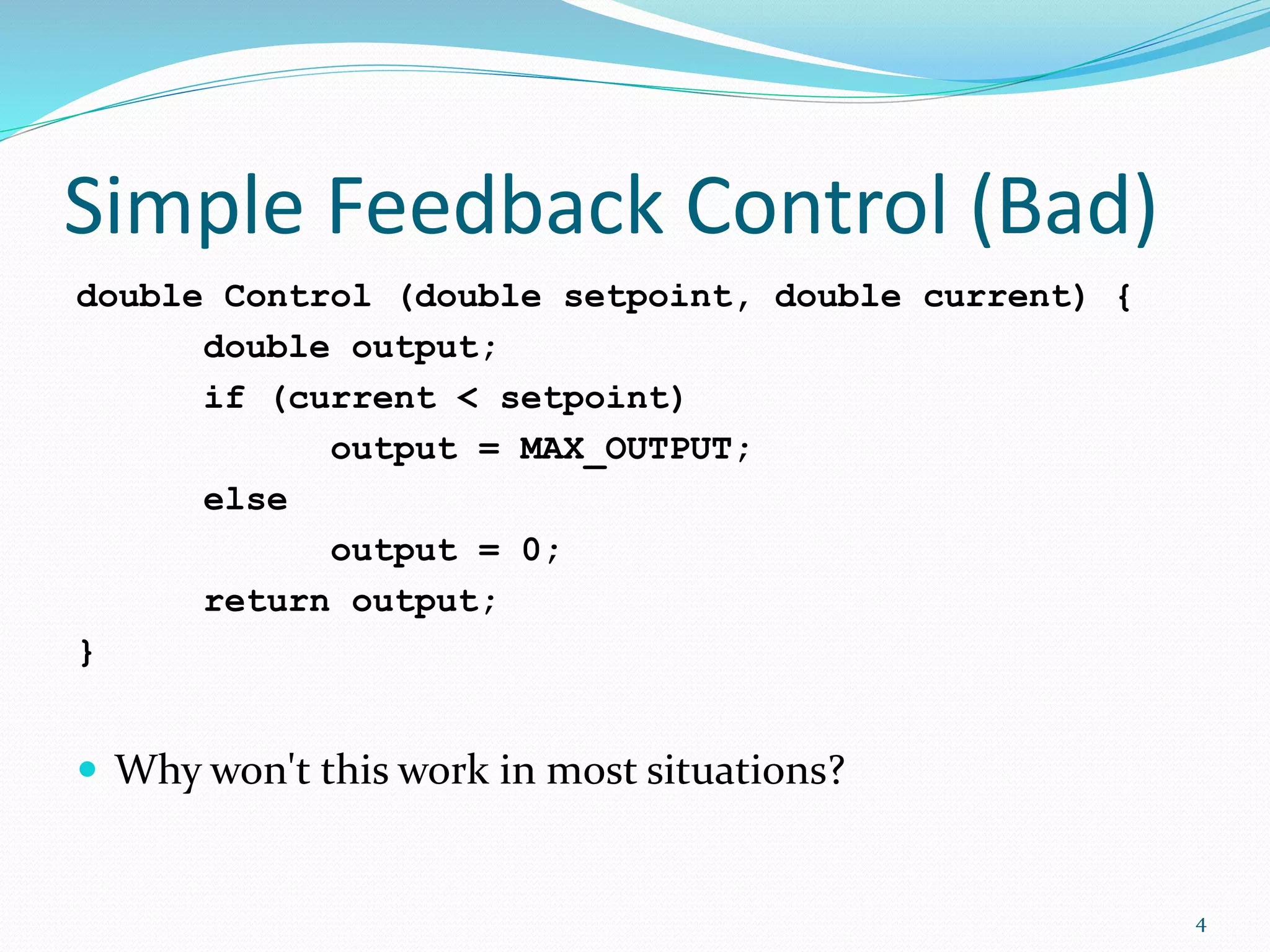

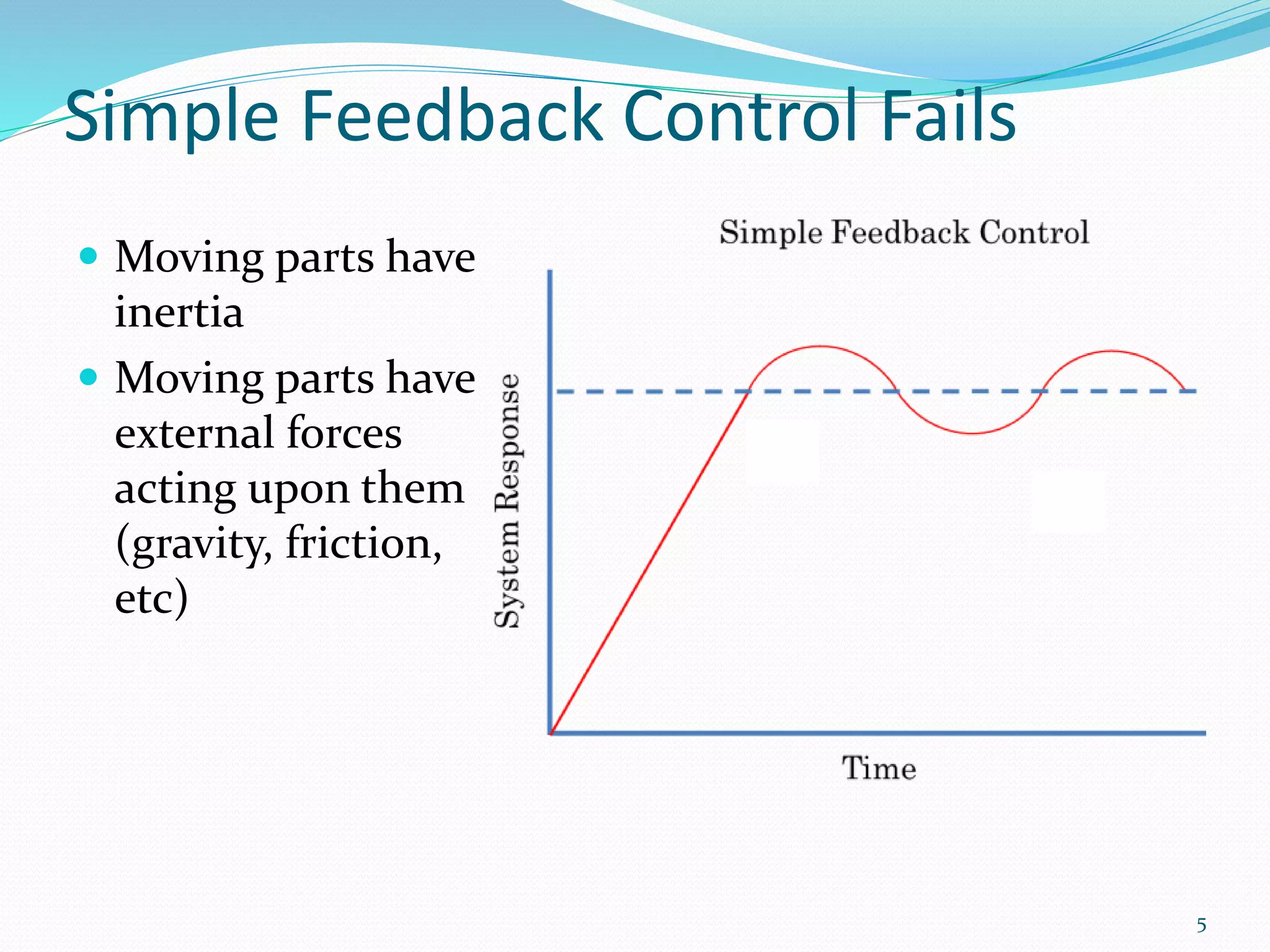

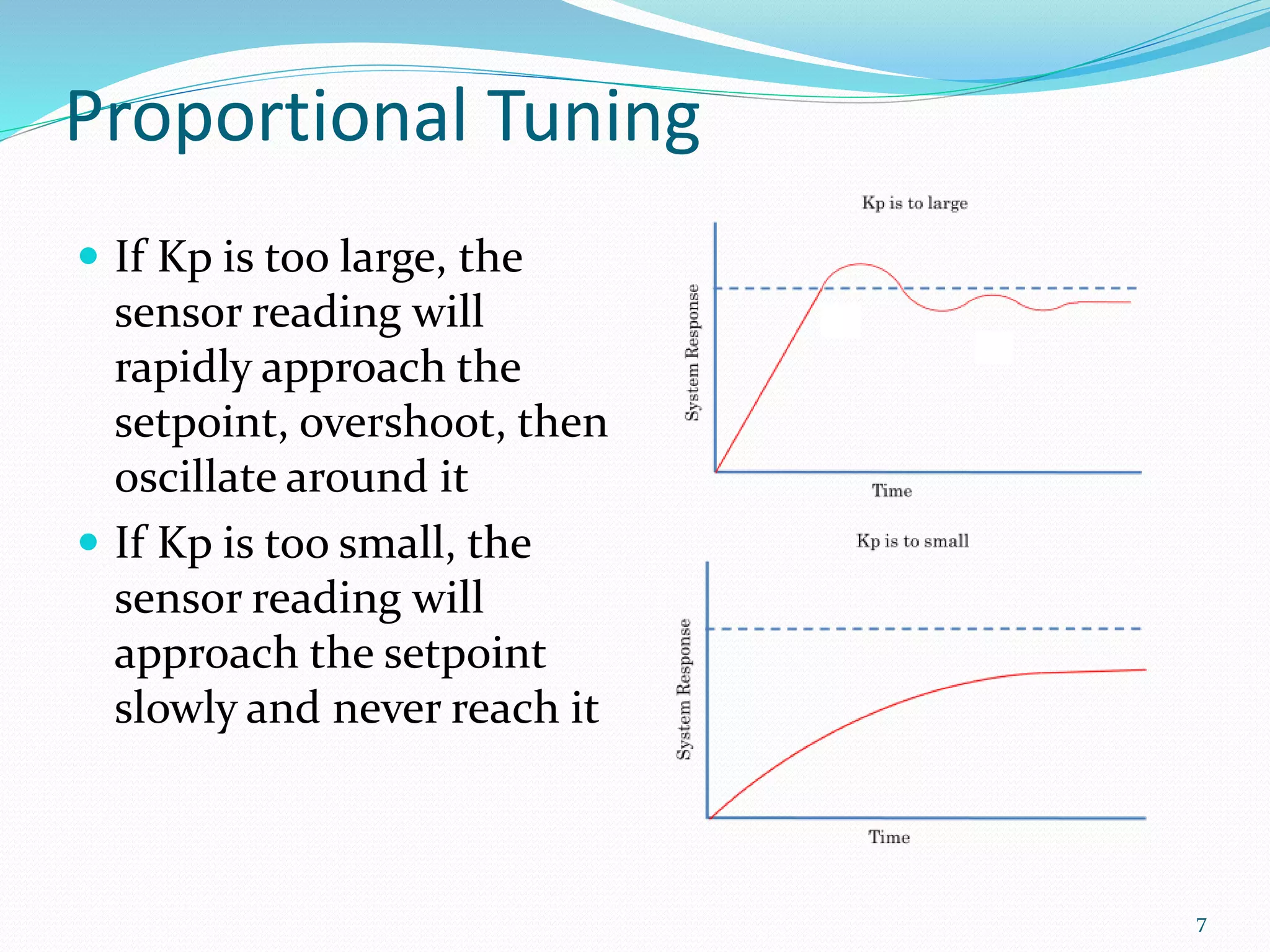

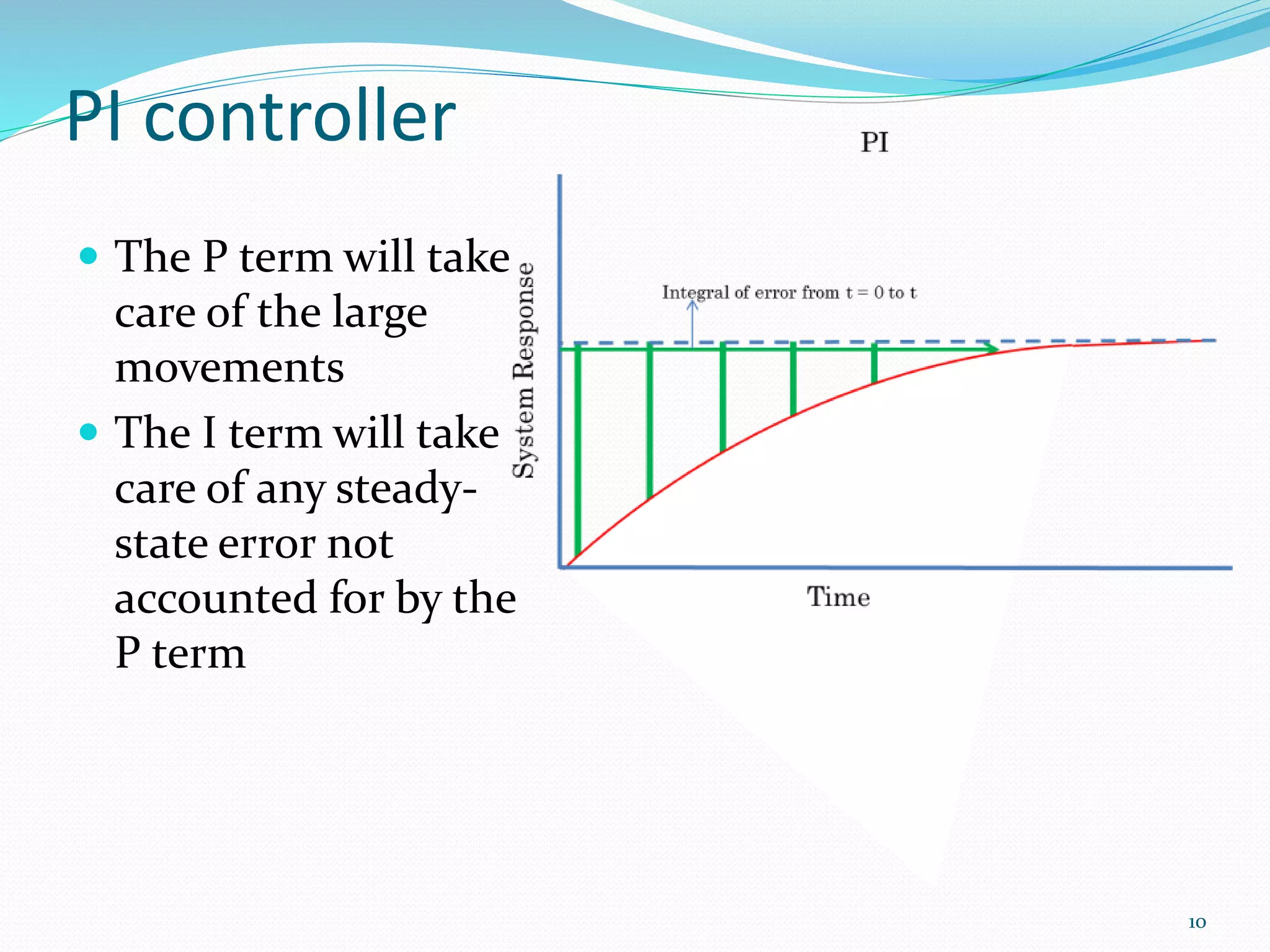

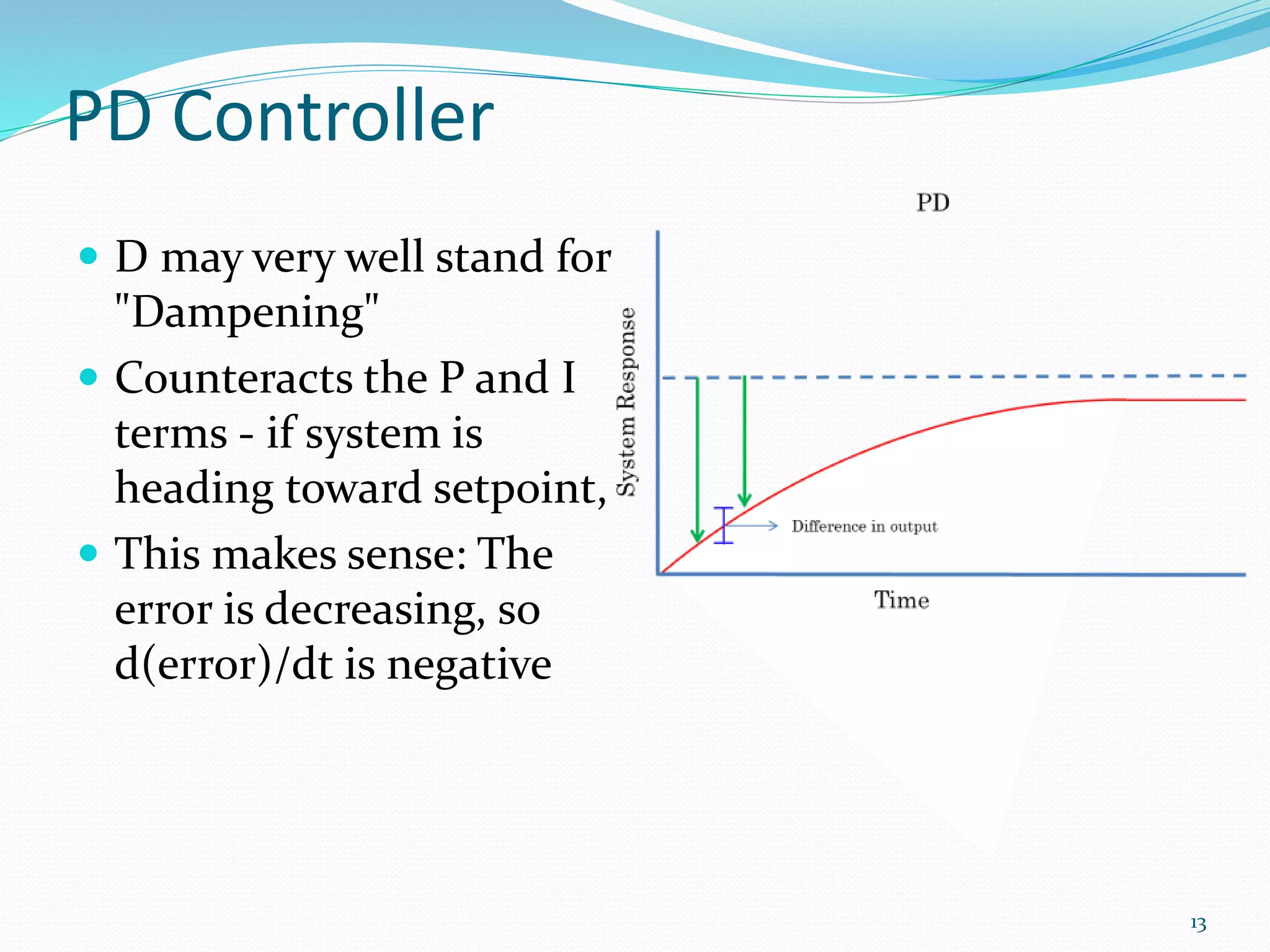

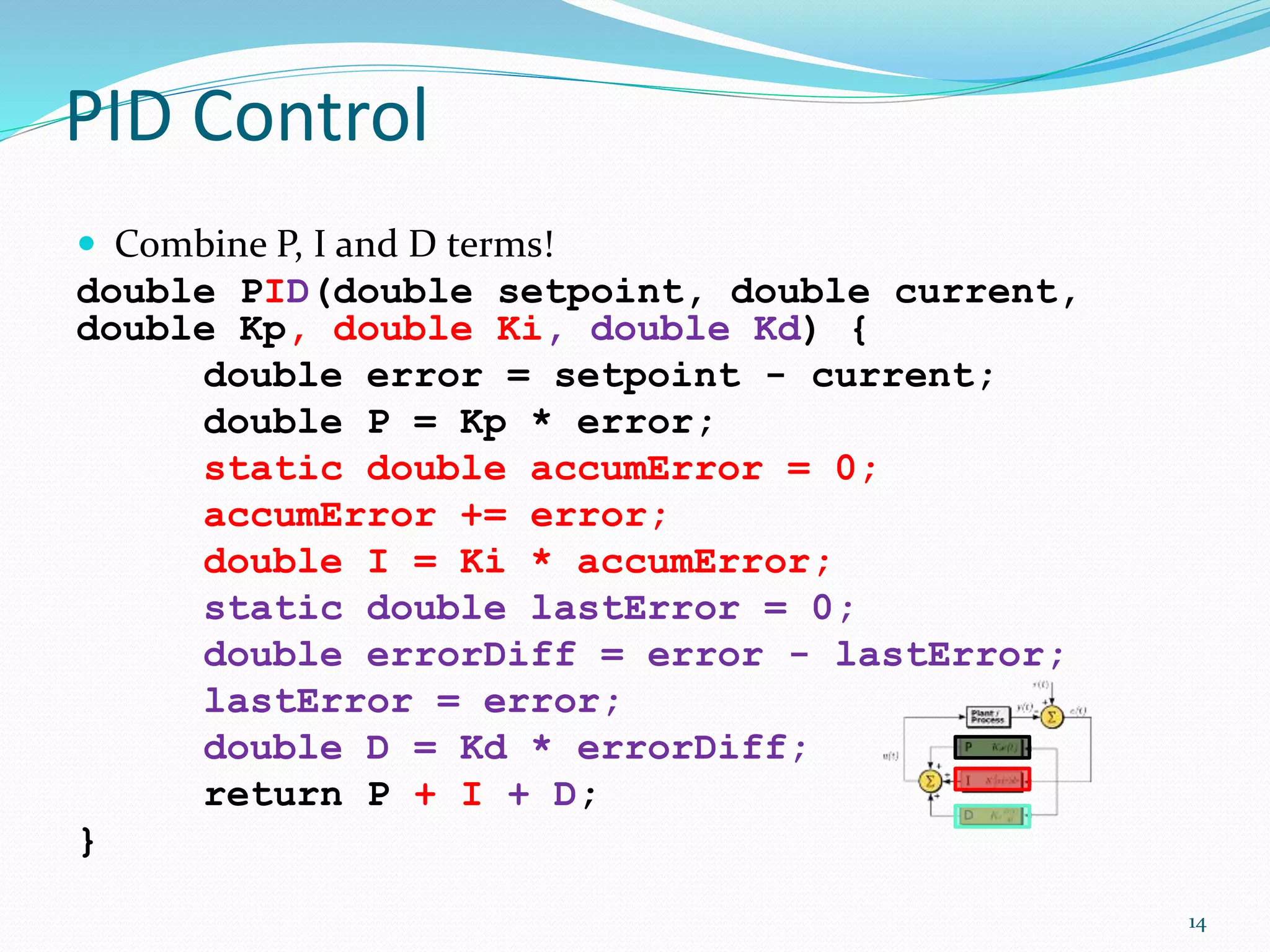

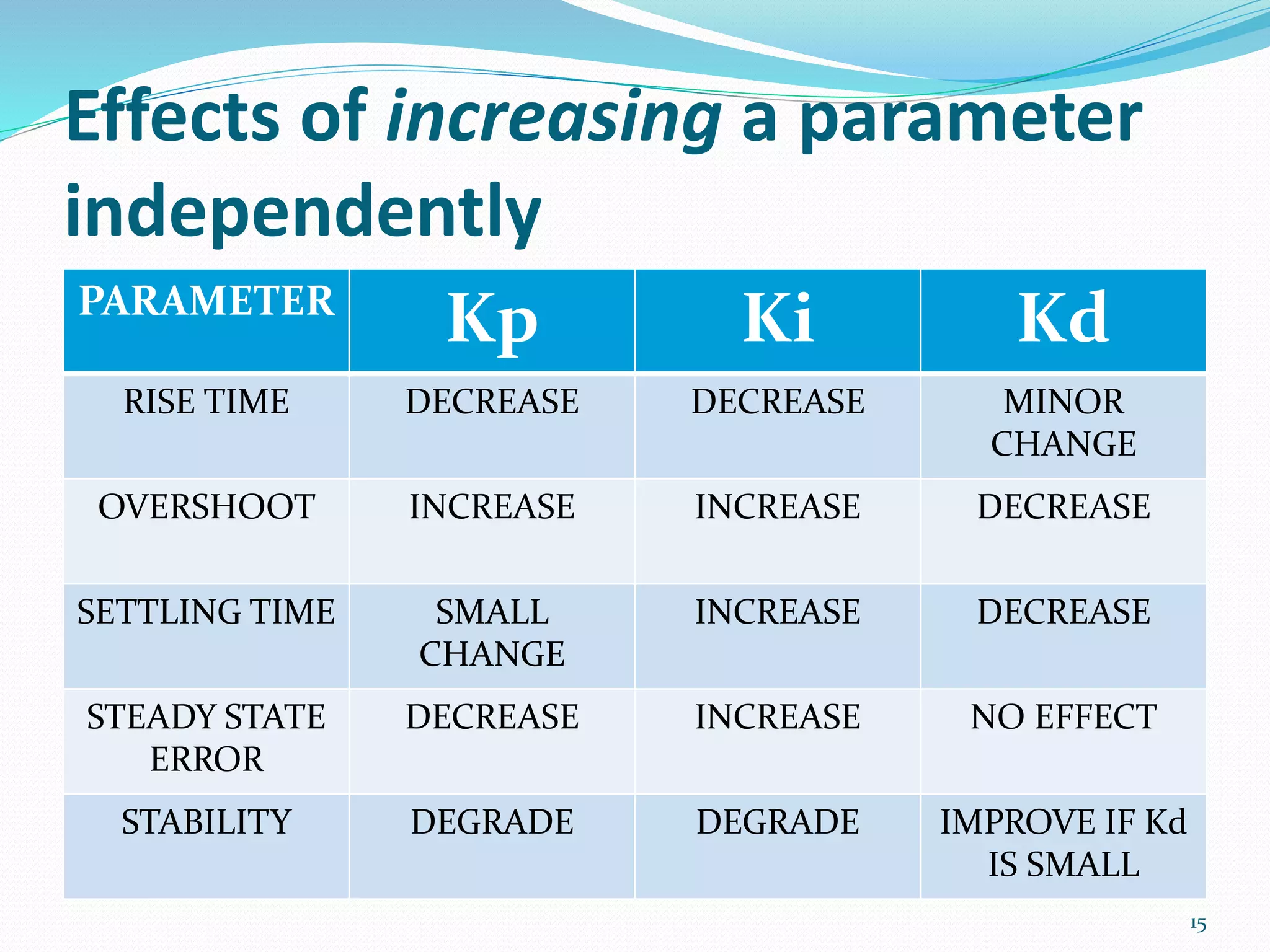

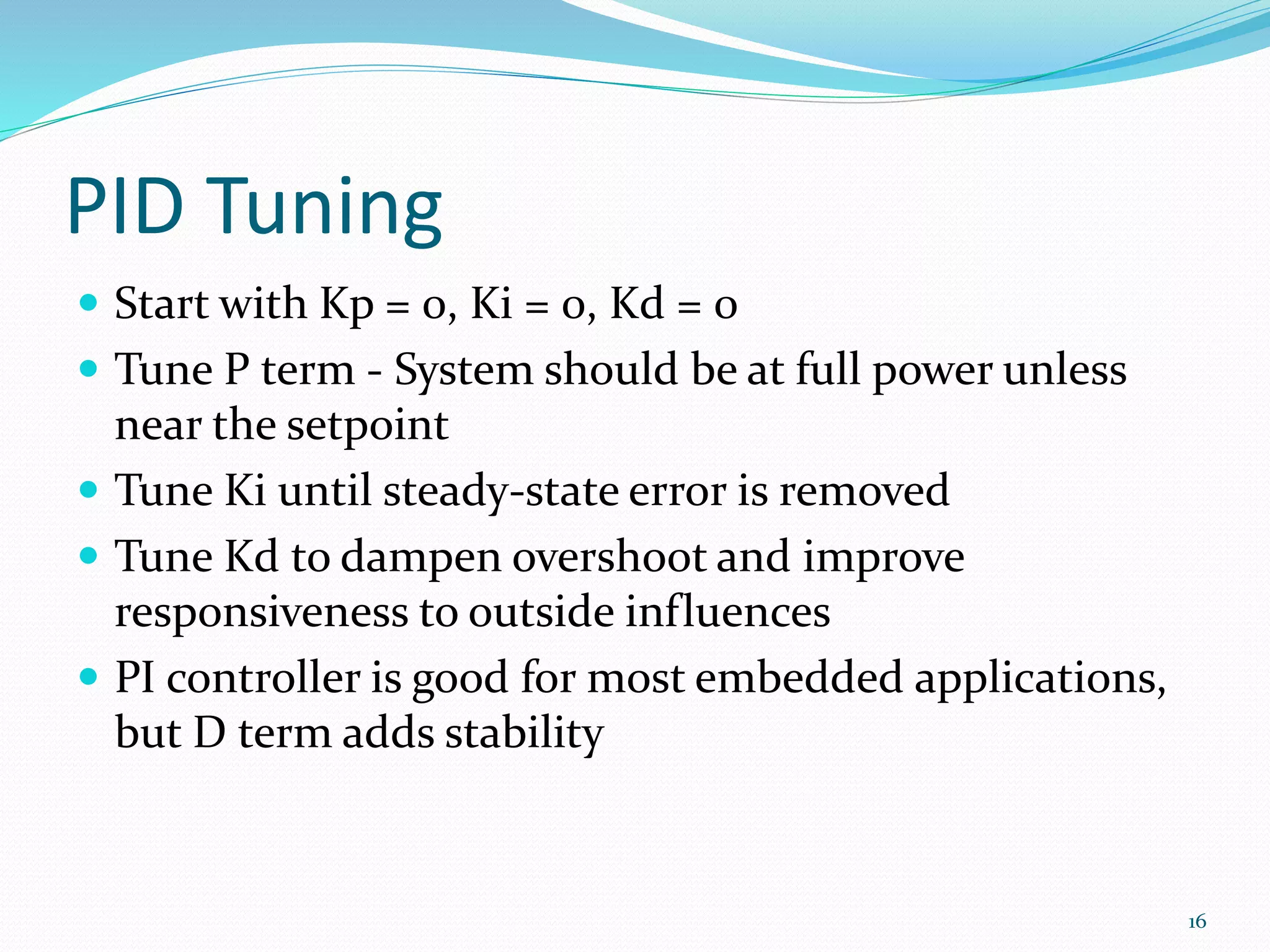

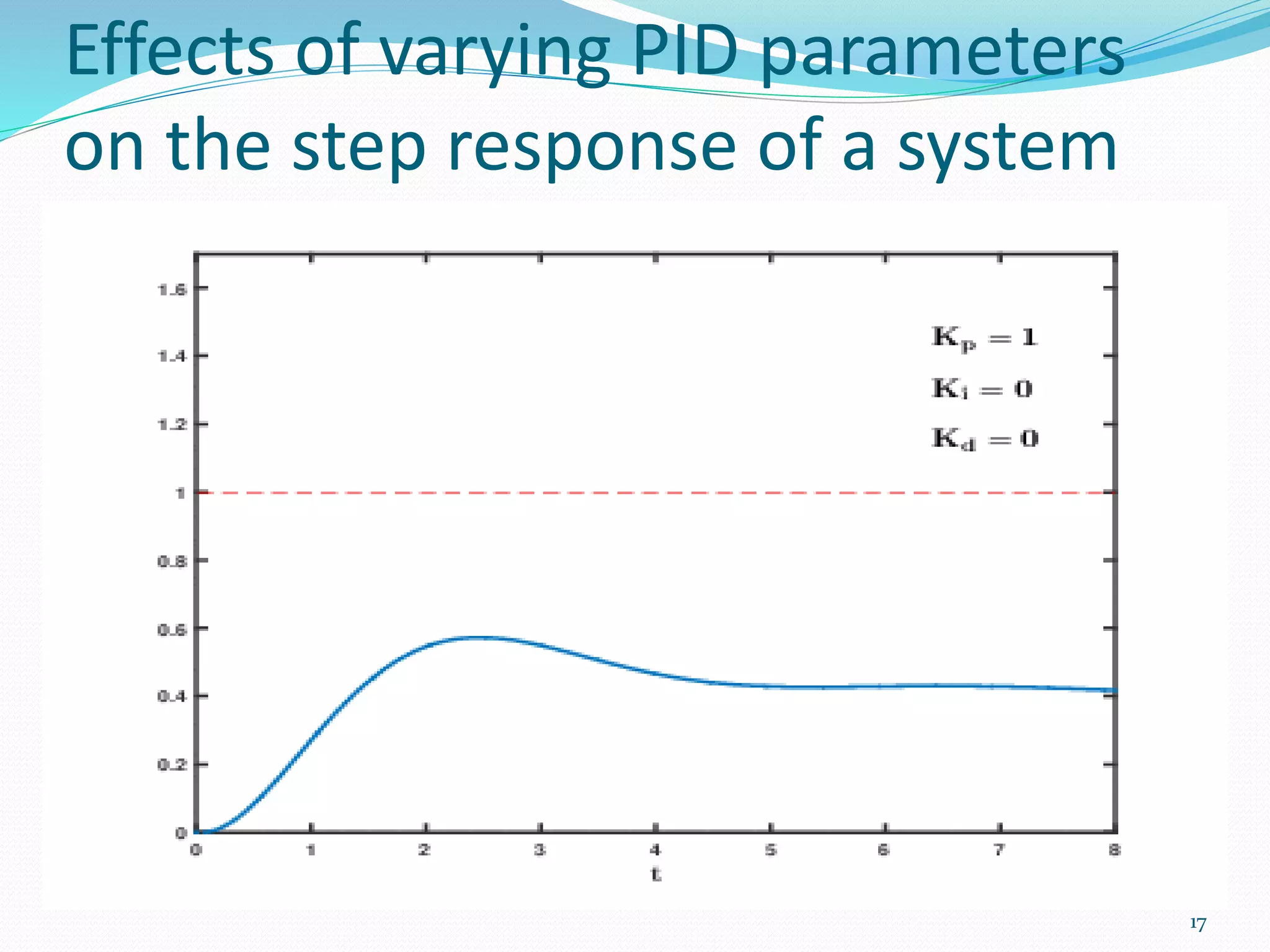

The document discusses feedback control systems, specifically focusing on Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control methods. It outlines the mechanics of each control type (P, PI, PD, and PID), their applications, and the significance of tuning parameters for optimal performance. Additionally, it addresses common issues and solutions related to system inertia and external forces.