This document provides an overview of topics to be covered in a lecture on single neuron models. It will discuss:

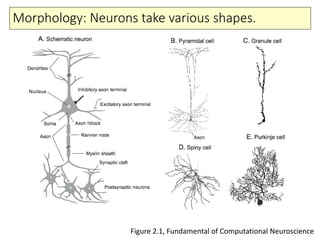

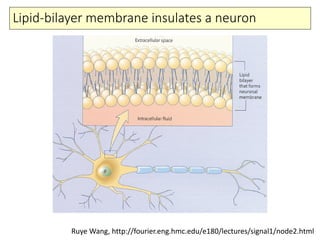

1) The basic anatomy and physiology of neurons including their morphology and membrane properties.

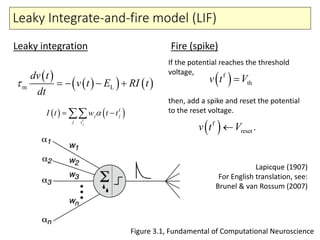

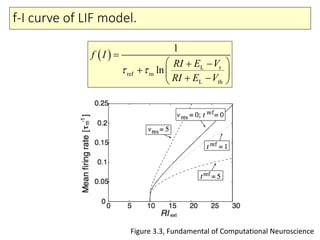

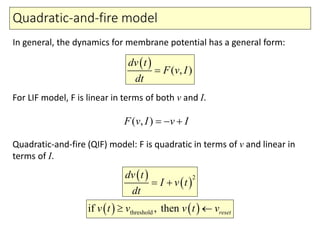

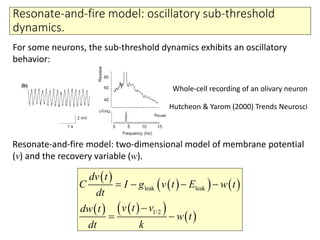

2) Phenomenological models of subthreshold dynamics like the integrate-and-fire, quadratic-and-fire, and resonate-and-fire models.

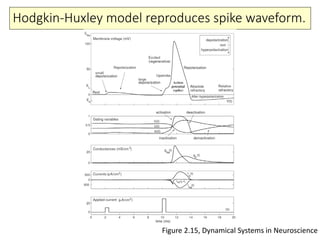

3) Biophysical models of spiking mechanisms including the Hodgkin-Huxley model and its use of ion channels and master equations.

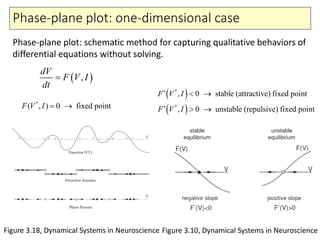

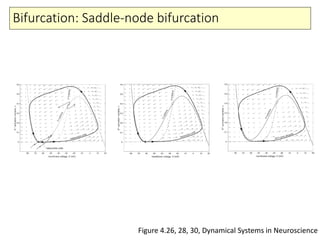

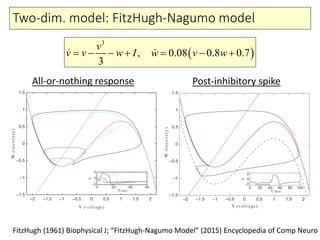

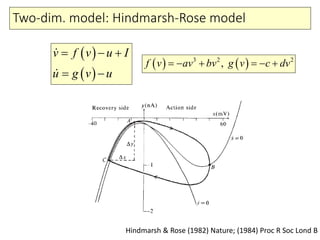

4) Analysis techniques like phase plots and bifurcation analysis applied to models like FitzHugh-Nagumo and Hindmarsh-Rose.

5) Modern single neuron models such

![Ion channels: Nernst equation.

Figure 6.3, Fundamental of Computational Neuroscience

[ ]

[ ]

out

ion in out

in

ion

ln

ion

RT

E E E

zF

≡ − =

EoutEin Nernst equation

[ ]

[ ]

( )

out

out in

in

out

in

ion

ion

zF

E zFRT E E

RT

zF

E

RT

e

e

e

−

− −

−

= =

in[ ] 140mMK+

= out[ ] 3mMK+

=

[ ]

[ ]

out

in

3

ln 61.5ln 102mV

140

K

KRT

E

F K

= = = −

Potassium ion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ss201601singleneurons-160830235901/85/JAIST-2016-01-Single-neuron-models-16-320.jpg)