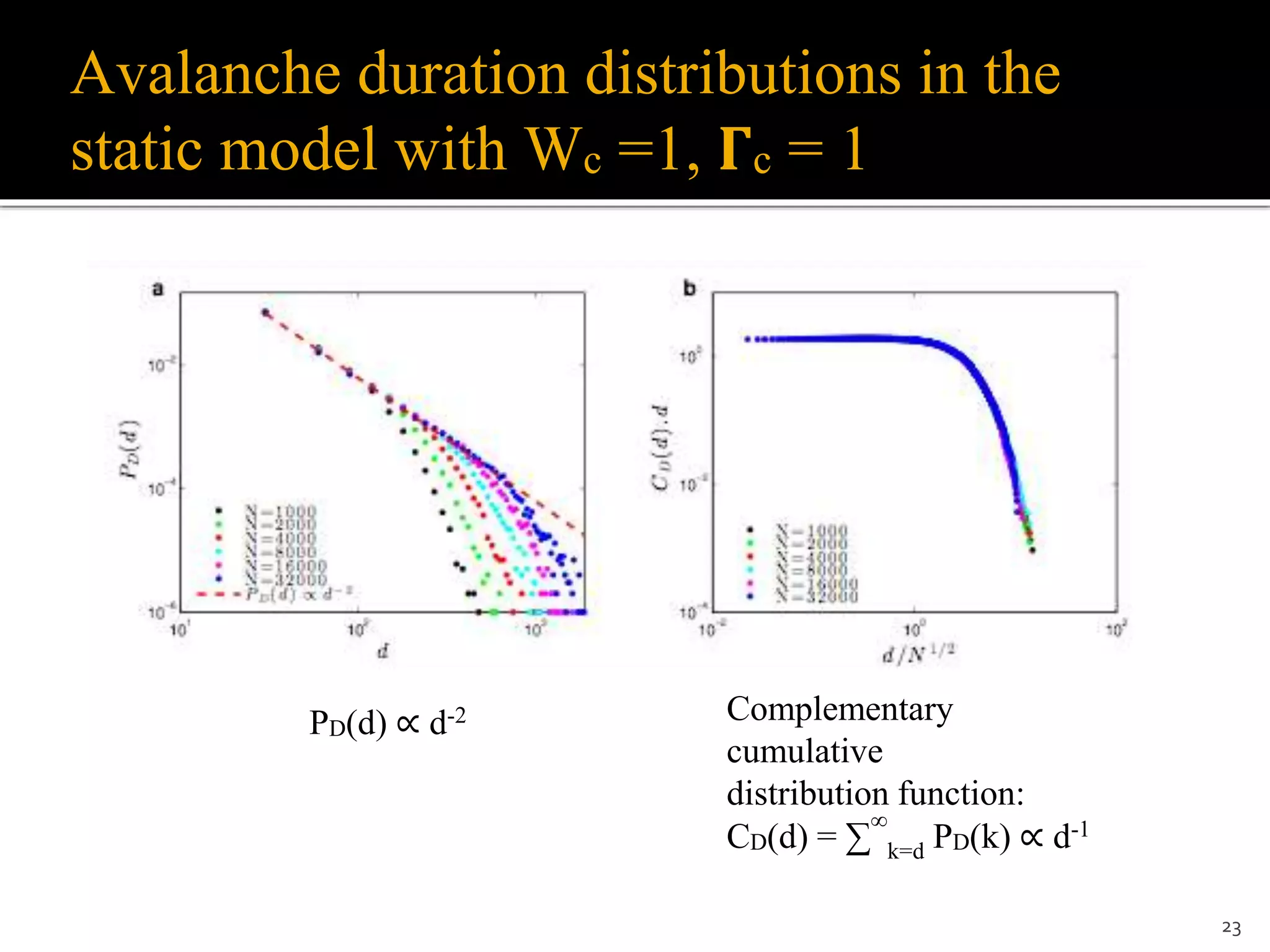

1) The document discusses a model of stochastic spiking neural networks where dynamical neuronal gains produce self-organized criticality. Introducing dynamic neuronal gains Γi[t] in addition to dynamic synaptic weights Wij[t] allows the system to self-organize toward a critical region without requiring divergent timescales.

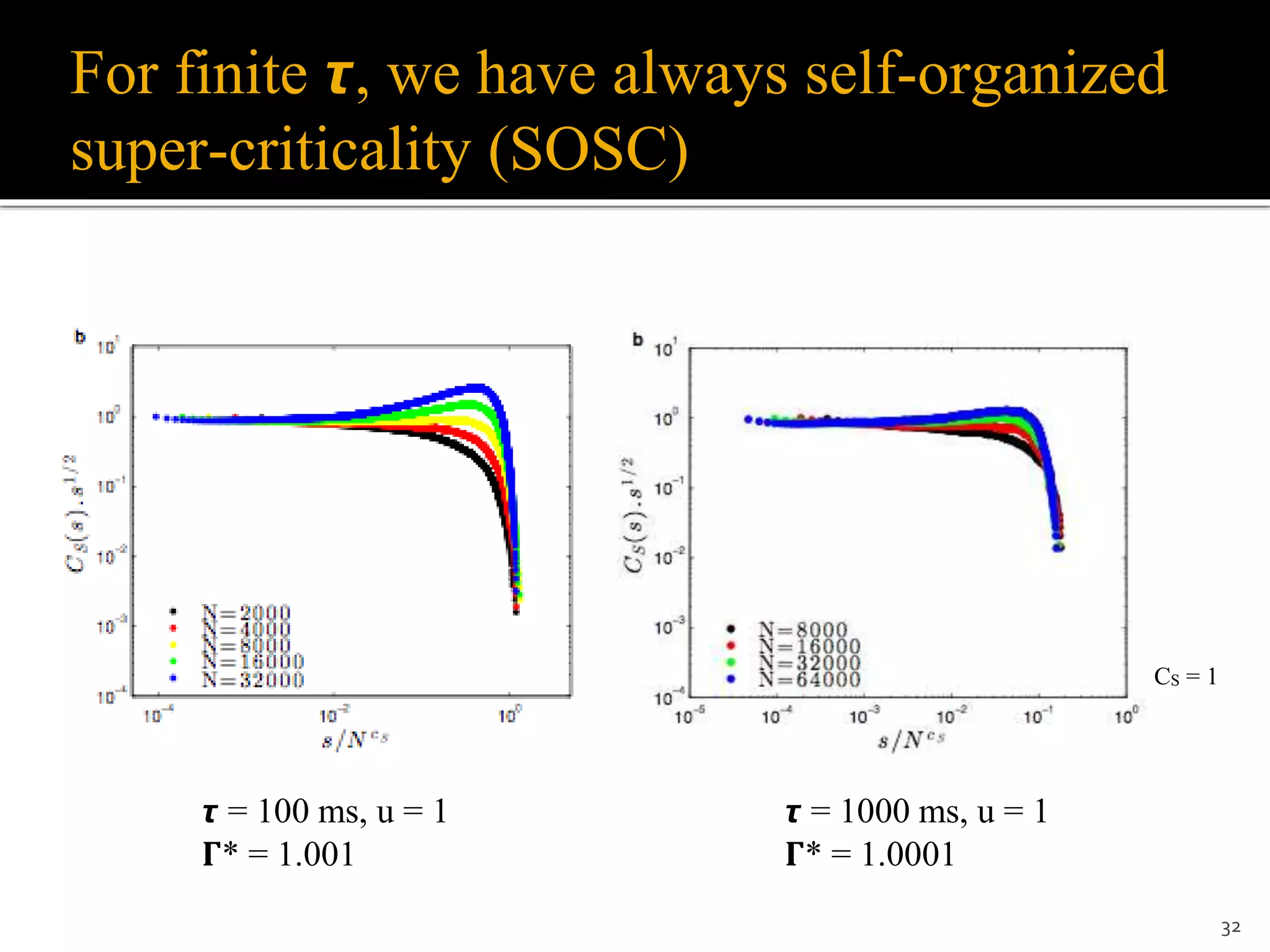

2) For finite recovery timescales τ, the model exhibits self-organized supercriticality (SOSC) where the average neuronal gain Γ* is always slightly above critical. SOSC may help explain biological phenomena like large avalanches and epileptic activity.

3) The model provides a new framework to study self-organized phenomena in neuronal networks, including potential analytic solutions and

![Allan Turing (1950)

Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59, 433-460.

Is there a corresponding phenomenon [criticality] for minds, and

is there one for machines? There does seem to be one for the

human mind. The majority of them seems to be subcritical, i.e., to

correspond in this analogy to piles of subcritical size. An idea

presented to such a mind will on average give rise to less than one

idea in reply.

A smallish proportion are supercritical. An idea presented to such

a mind may give rise to a whole "theory" consisting of secondary,

tertiary and more remote ideas. (...) Adhering to this analogy we

ask, "Can a machine be made to be supercritical?"

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-4-2048.jpg)

![Our model: Stochastic discrete time spiking

neurons (Galves & Löcherbach, 2013)

i = 1, 2, …, N neurons Xi[t] = 1 (spike)

Vi[t+1] = 0 reset if Xi[t] = 1

Vi[t+1] = μVi[t] + I + N-1 ∑j Wij Xj[t] if Xi[t] = 0

Prob( Xi[t+1] = 1 ) = Φ(Vi[t])

Φ = firing probability function

0 ≤ Φ(V) ≤ 1

7

All-to-all network](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-6-2048.jpg)

![Examples of firing functions

8

1

VT VS V

r = 1

r > 1

r < 1

Φ(V) For VT < V < VS: Φ(V) = [ 𝚪(V-VT) ]r

𝚪 = Neuronal Gain](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-7-2048.jpg)

![Mean field approach

Order parameter: ρ[t] = 1/N ∑i Xi[t]

MF approximation:

1/N ∑i Wij Xi[t] = W ρ[t], where W = <Wij>

Voltages evolve as:

Vi[t+1] = 0 if Xi[t] = 1

Vi[t+1] = μVi[t] + I + Wρ if Xi[t] = 0

ρ[t] = ∫ Φ(V) pt(V) dV

In the stationary state, the voltages assume a discrete stationary set of values Uk.

The density of neurons with Uk is 𝛈k . Normalization: ∑ 𝛈k = 1

So, in the stationary state, ρ = ∑k Φ(Uk) 𝛈k

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-8-2048.jpg)

![Mean field stationary states

Uk = Voltage of the k-th stationary peak

𝛈k = peak height

μ > 0 case (several peaks, only numeric solutions):

ρ = ∑k=1 Φ(Uk) ηk

Uk = μ Uk-1 + I + W ρ

ηk = [1- Φ(Uk-1)] ηk-1

η0 = ρ = 1 - ∑k=1 ηk (Normalization)

11

Uk

η0 = ρ η1

η2

η3

η4

Φ

(1- Φ)η0

Φ

Φ

Φ

(1- Φ)η1

(1- Φ)η2

(1- Φ)η3

U1 U2 U3 U4U0 = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-10-2048.jpg)

![ Due to the one step refractory period,

we cannot have ρ > 1/2.

ρ(𝚪b,Wb) = 1/2 defines a bifurcation

line (𝚪b = 2/Wb for the μ = 0 case)

Cycles-2 occur because there is only

two peaks, with U1 > VS

Deterministic dynamics since now

Φ(U1 > VS) = 1

𝛈0[t+1] = 𝛈1[t] = 1 - ρ[t]

𝛈1[t+1] = 𝛈0[t] = ρ[t]

Cycle dynamics:

ρ[t+1] = 1 - ρ[t]

Solutions occur for any values inside

the region [VS/W, (W-VS)/W]

Observation: marginally stable cycles-2

13

VS

Φ(U1) = 1

V

1

VVS

1

Φ(U1) = 1

0

0

𝛈1[t]

𝛈1[t+1]

𝛈1[t+1]

𝛈1[t]

𝛈0[t+1]

𝛈0[t]

𝛈0[t]

𝛈0[t+1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-12-2048.jpg)

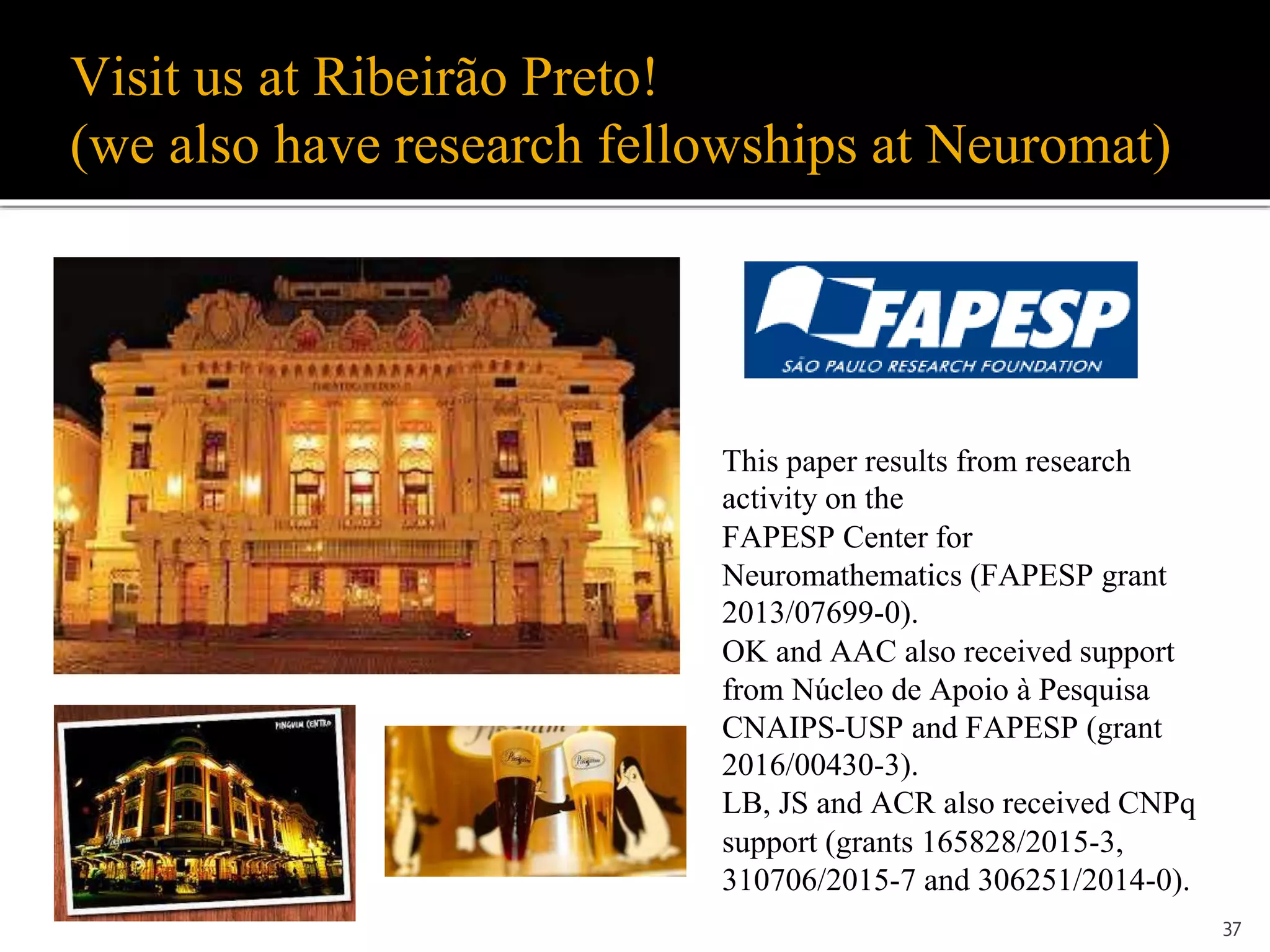

![Case μ = 0

14

μ = 0 case (only two peaks, analytic solutions):

η0 = ρ = Φ(U1) η1 = Φ(I+Wρ) (1 - ρ)

η1 = 1 - ρ (Normalization)

With:

Φ(x) = 0 for x < VT

Φ(x) = [ 𝚪(x-VT) ]r for VT < x < VS = VT + 1/𝚪

Φ(x) = 1 for x > VS

Very easy Math! (polinomial equations). Solve for 0 < ρ <1/2:

ρ = [𝚪(I+Wρ-VT)]r (1-ρ)

ρ

η1 = 1- ρ

1-Φ

1

Φ

U1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-13-2048.jpg)

![Parameters of the firing function Φ

15

1

Threshold voltage VT Saturation voltage VS =VT + 1/𝚪 V

r = 1

r > 1

r < 1

Φ(V) For VT < V < VS: Φ(V) = [𝚪(V-VT)]r

𝚪 = Neuronal Gain](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-14-2048.jpg)

![μ = 0, linear saturating case r = 1, VT = 0

(Larremore et al., PRL 2014) But they do not report phase transitions

16

• Case r = 1, solve for 0 < ρ <1/2:

ρ = [𝚪(I + Wρ − VT)] (1 − ρ) or:

𝚪W ρ2 + (1 − 𝚪W + 𝚪I − 𝚪VT) ρ + 𝚪VT − 𝚪I = 0

• Solutions:

• Continuous and discontinuous phase transitions here

Φ

V](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-15-2048.jpg)

![Why to separate the average gain 𝚪 from the

average synaptic weight W?

In a biological network, each

neuron i has a neuronal gain 𝚪i[t]

located at the Axonal Initial

Segment (AIS). Its dynamics is

linked to sodium channels.

The synapses Wij[t] are located at

the dendrites, very far from the

axon. Its dynamics is due to

neurotransmitter vesicle

depletion.

So, although in our model they

appear always together as 𝚪W,

this is due to the use of point like

neurons. A neuron with at least

two compartments (dendrite +

soma) would segregate these

variables.

25AIS, 𝚪i[t]

Wij[t]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-24-2048.jpg)

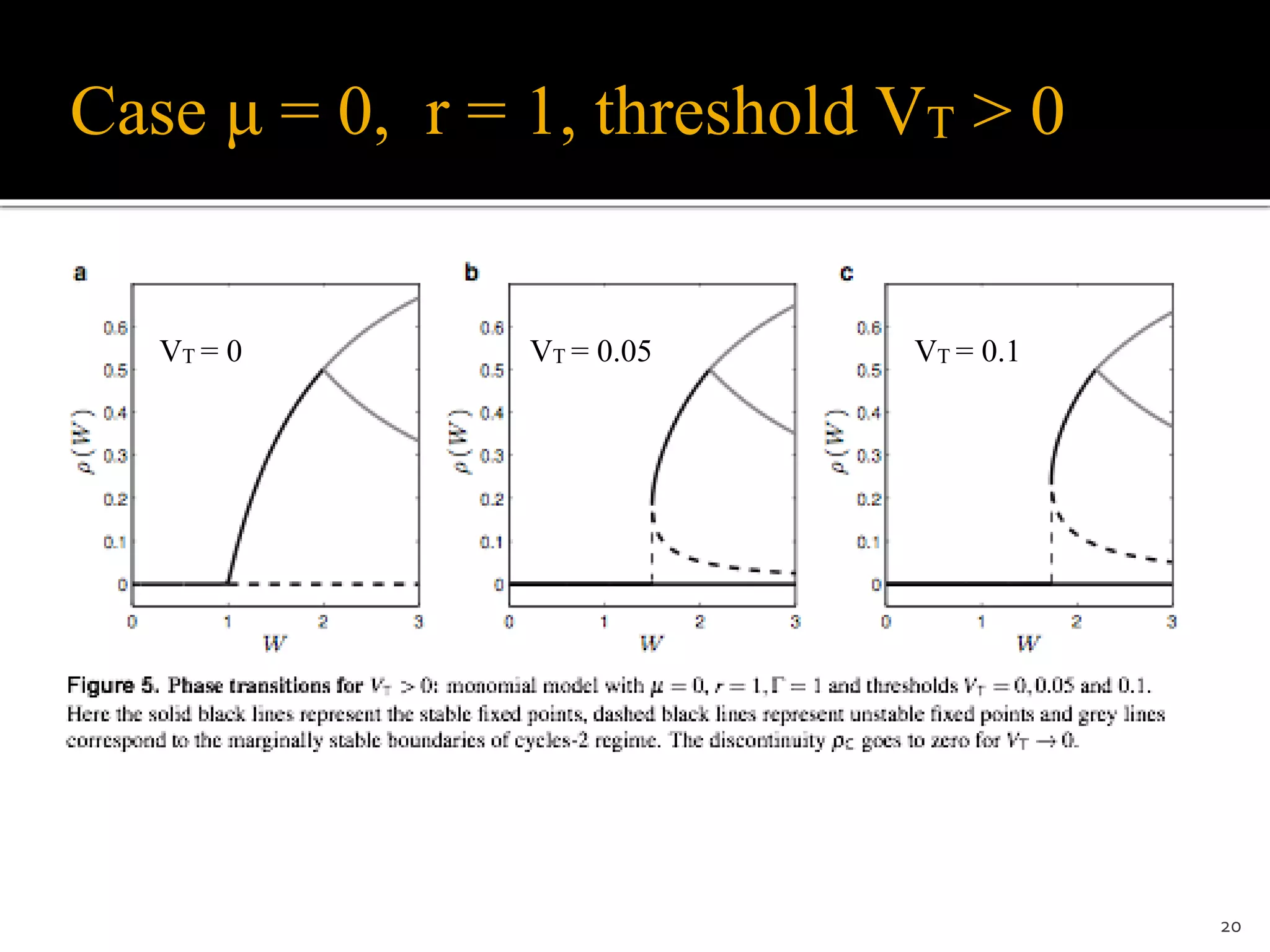

![Dynamic synapses and dynamic gains

Dynamic synapses (Levina et al., 2007; Levina et al.,

2009; Bonachela et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2015, Campos

et al., 2016):

Wij[t+1] = Wij[t] + 1/𝞽 (A − Wij[t]) − u Wij[t] Xj[t]

Dynamic gains (Brochini et al., 2016):

𝚪i[t+1] = 𝚪i[t] + 1/𝞽 (A − 𝚪i[t]) − u 𝚪i[t] Xi[t]

Parameters range:

0 < u < 1, A > Wc (or A > 𝚪c)

All works with dynamic synapses used

𝞽 = O(N)

26

Wc, 𝚪c

A, 𝞽 u

O(N2) equations

O(N) equations!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-25-2048.jpg)

![The same problem occurs with dynamic gains

𝚪i[t+1] = 𝚪i[t] + 1/𝞽 (A - 𝚪i[t]) - u 𝚪i[t] Xi[t]

Averaging + stationary state:

1/𝞽 (A - 𝚪*) = u 𝚪* ρ

With ρ = ( 𝚪*- 𝚪c )/𝚪*, we get:

𝚪* = (𝚪c - Ax)/(1+x), with x = 1/(u𝞽)

We have 𝚪* → 𝚪c only for x → 0, that is, if 𝞽 → ∞ (not biological)

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-28-2048.jpg)

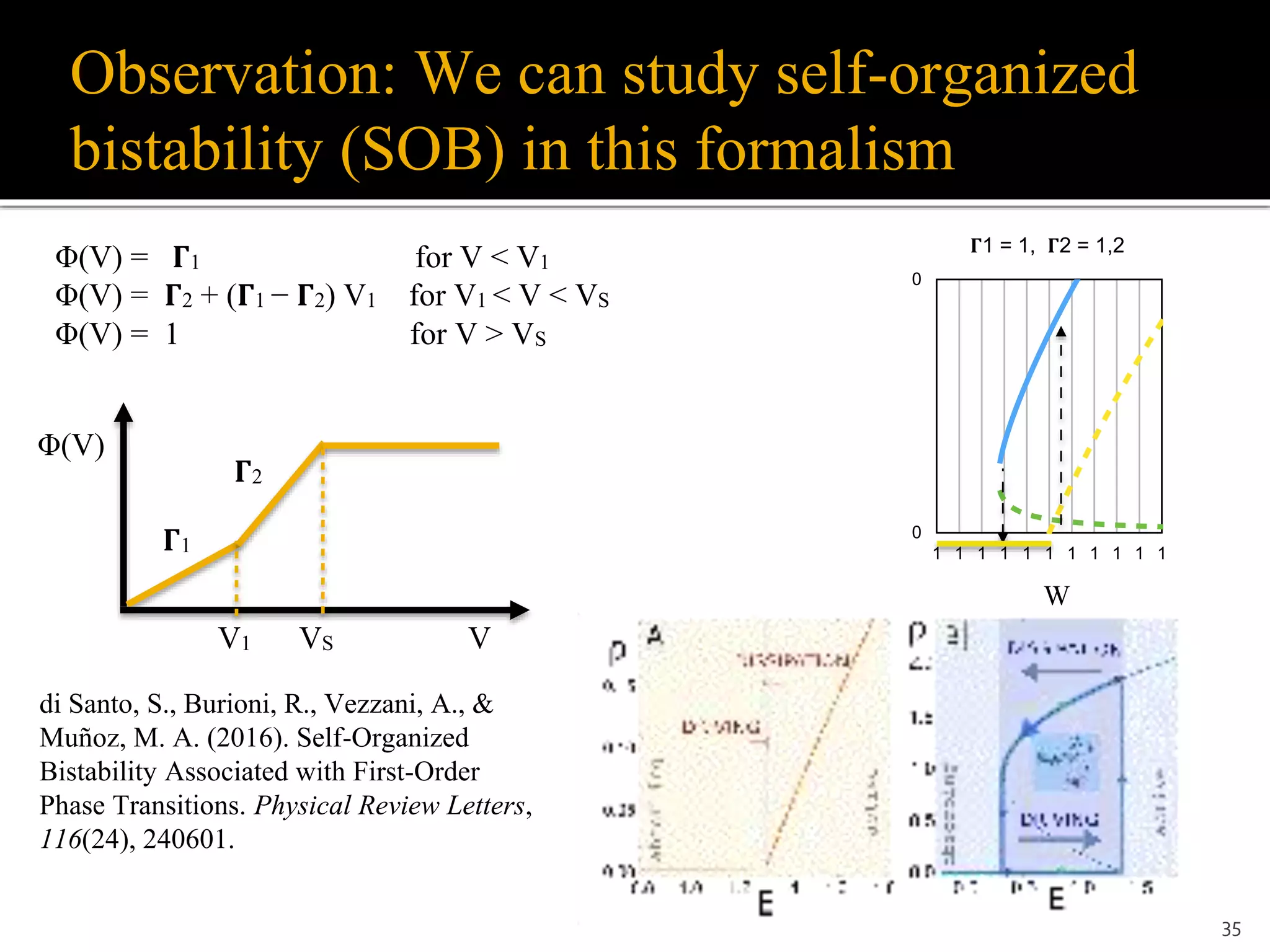

![Perpectives: a new neuronal network

formalism to be explored

More results, perhaps analytic, for the μ > 0 case.

Better study of dynamic synapses and dynamic gains

Other specific Φ functions (ex: Φ(V) = [𝚪(V-VT)]r/[1+[𝚪(V-VT)]r] = no 2-

cycles

Theorems for general Φ functions (ex: all linear piecewise functions give

analytic solutions)

Self-organized bistability (SOB)

Other network topologies (scale free, small world etc.)

Other kinds of couplings

Inhibitory neurons (ex: Larremore et al., 2014)

Very large networks: N > 106, synapses > 1010

Realistic topologies (ex: cortical Potjans-Diesmann model with layers and

different neuron populations, N=8x104, synapses = 3x108, Cordeiro et al.,

2016)

Etc., etc., etc…

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sosckinouchi2-171216155803/75/Neuronal-self-organized-criticality-34-2048.jpg)