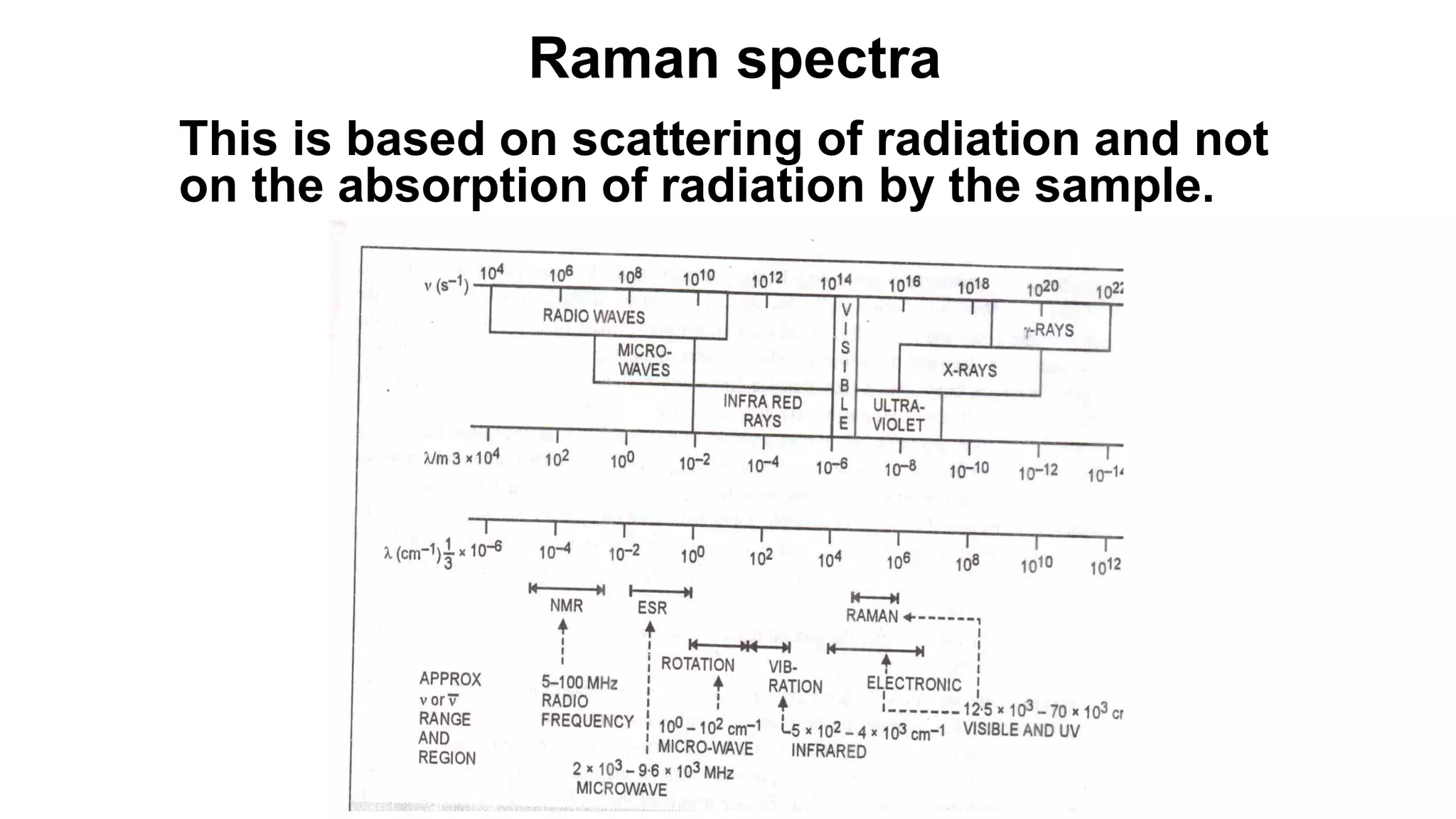

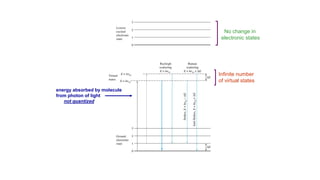

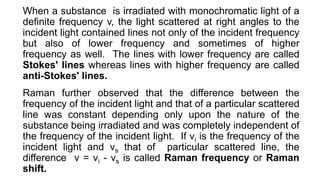

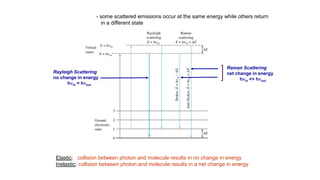

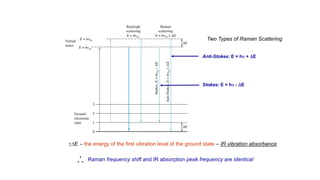

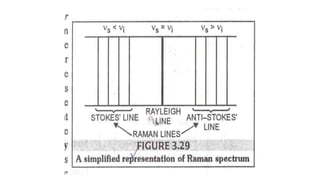

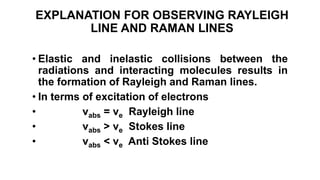

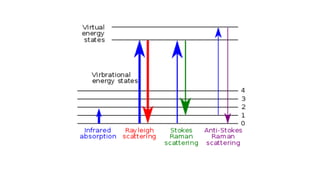

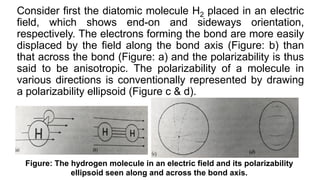

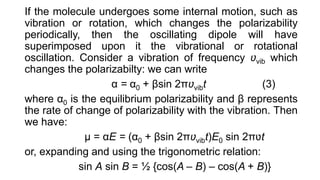

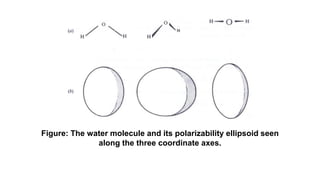

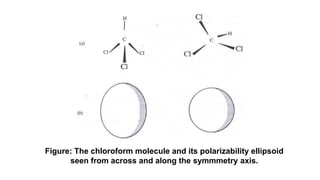

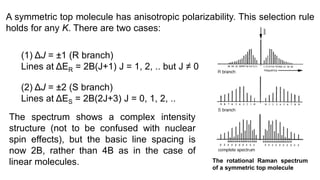

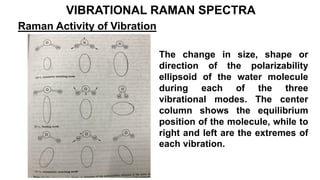

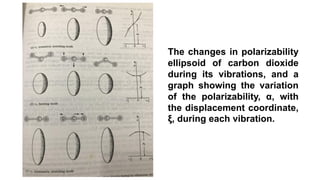

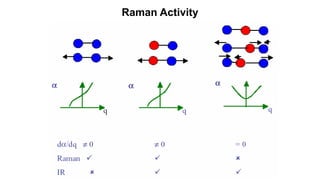

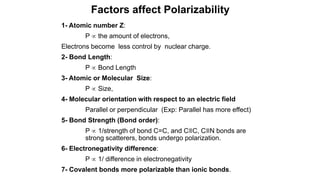

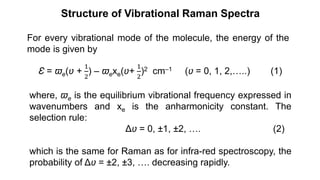

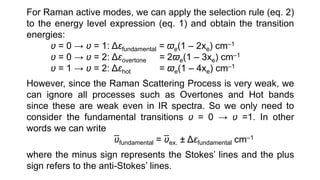

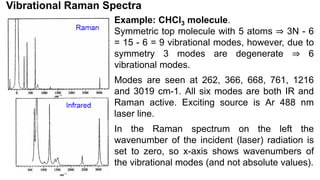

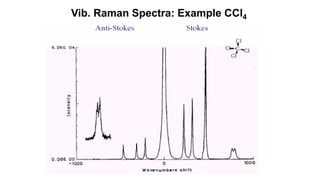

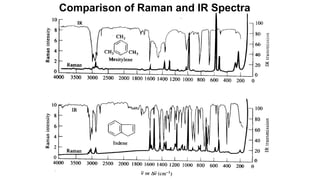

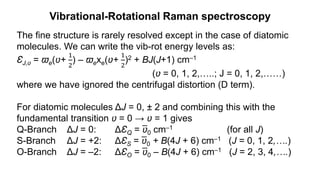

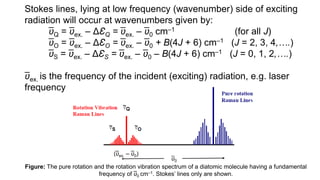

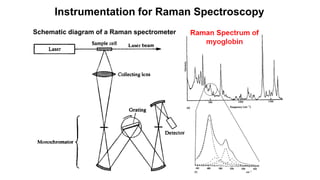

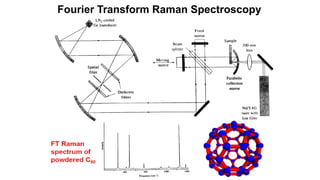

The document discusses Raman spectroscopy, which analyzes the scattering of light by molecules rather than light absorption. When a sample is irradiated with monochromatic light, most light is Rayleigh scattered at the same frequency, but a small amount is Raman scattered at lower (Stokes) or higher (anti-Stokes) frequencies. The frequency shift between incident and scattered light is independent of the incident light frequency and depends on molecular structure. Raman scattering occurs due to changes in molecular polarizability during vibrations or rotations. Spectra provide information about molecular vibrational and rotational energy levels.