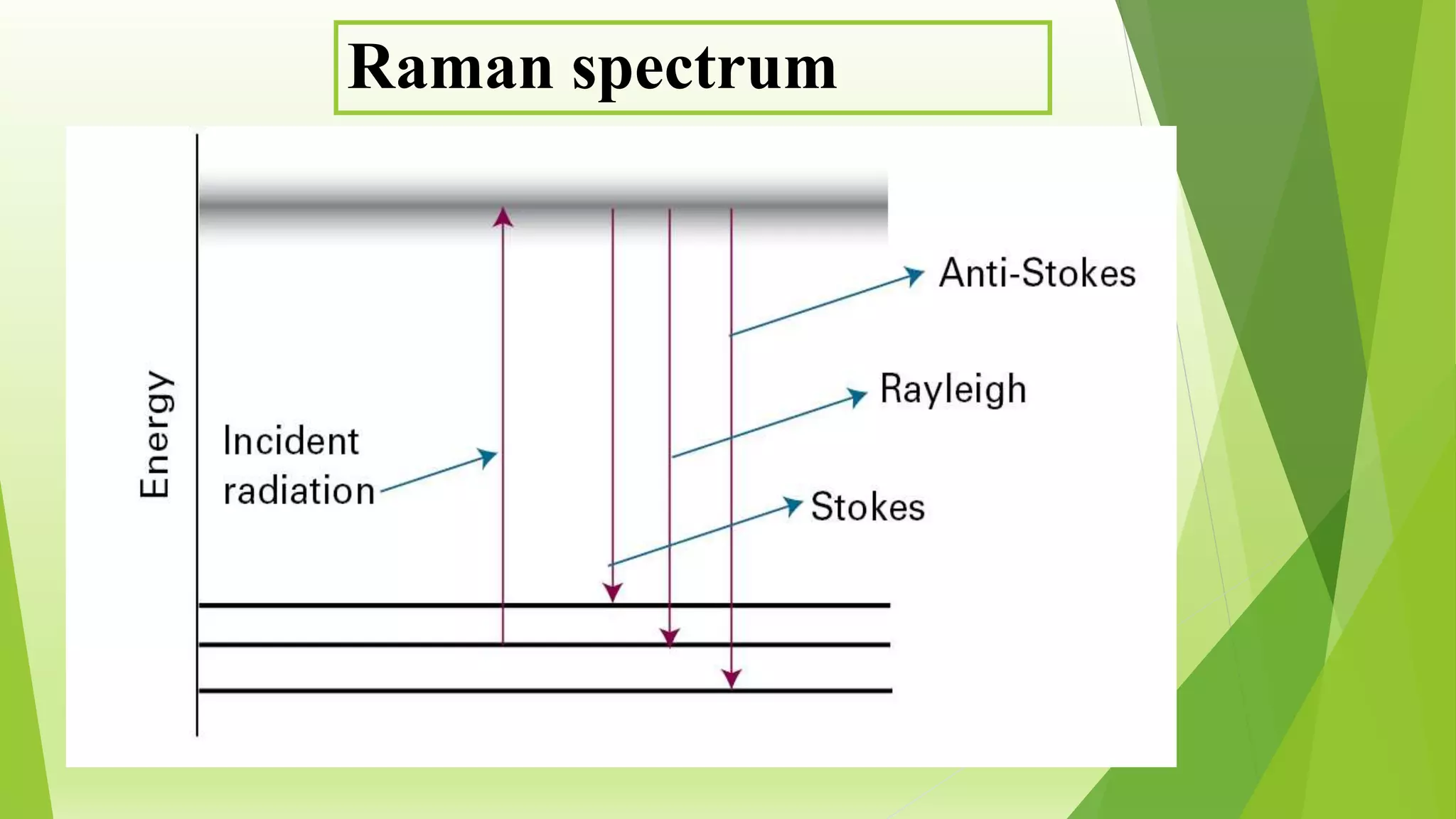

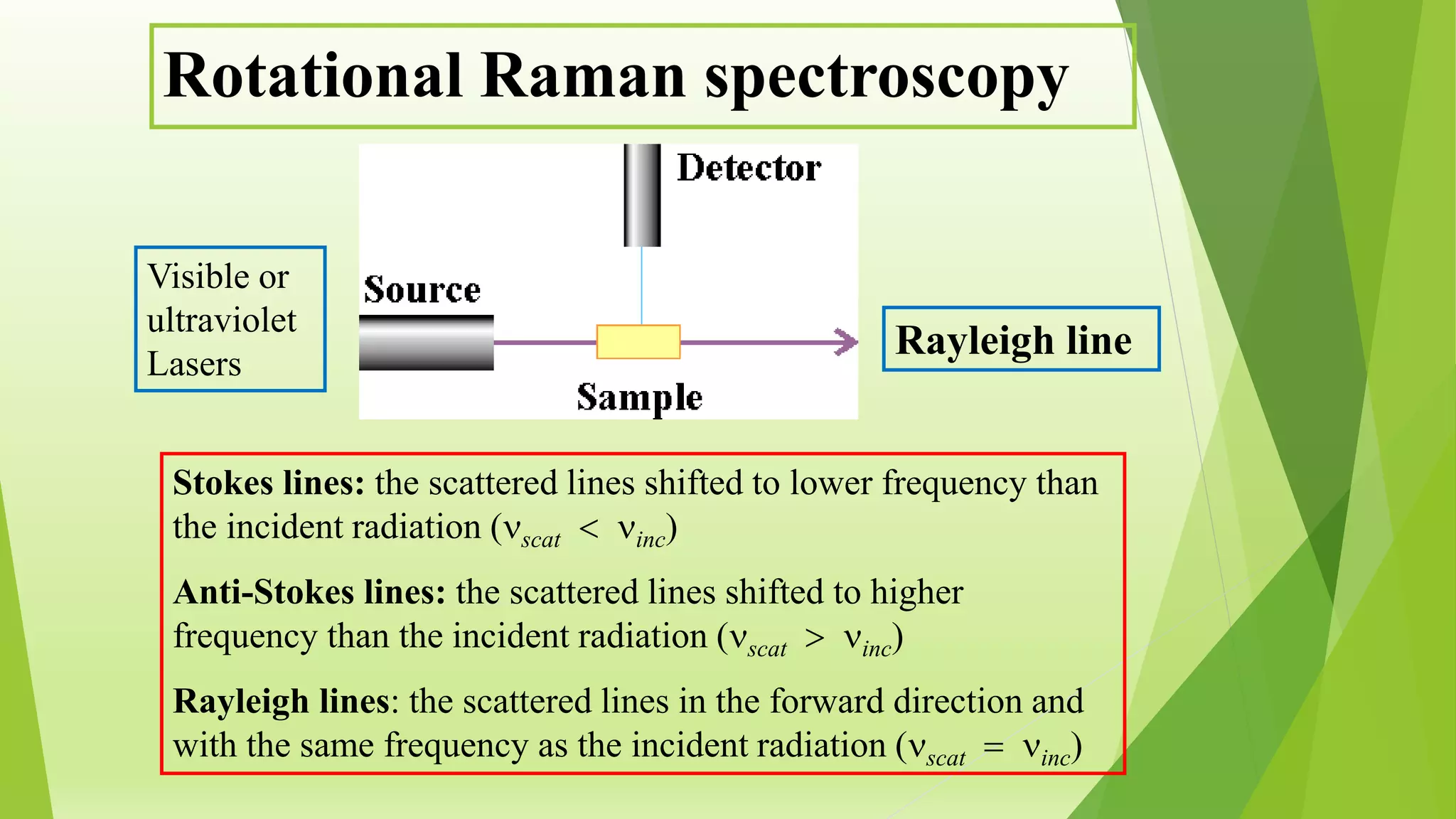

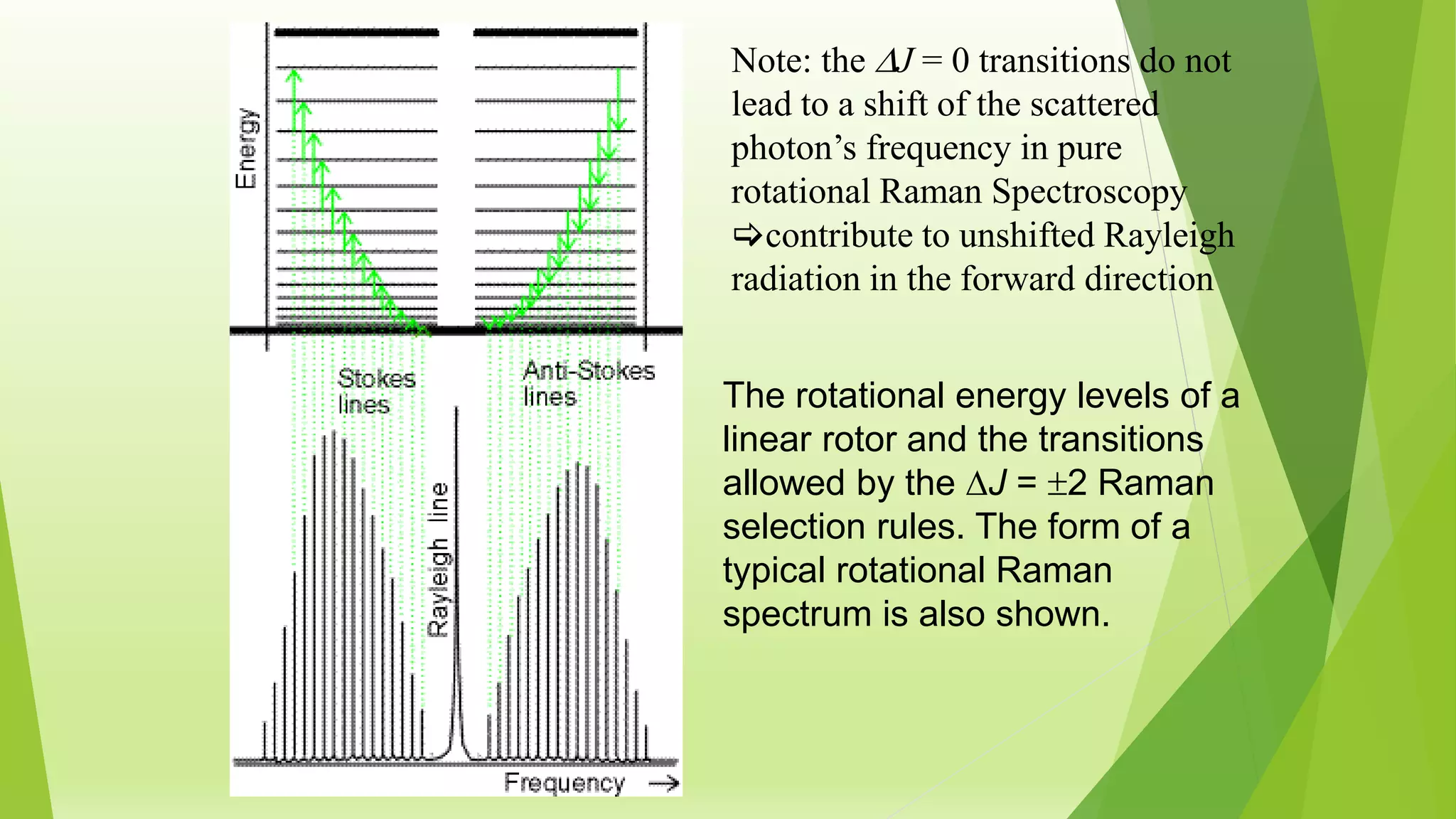

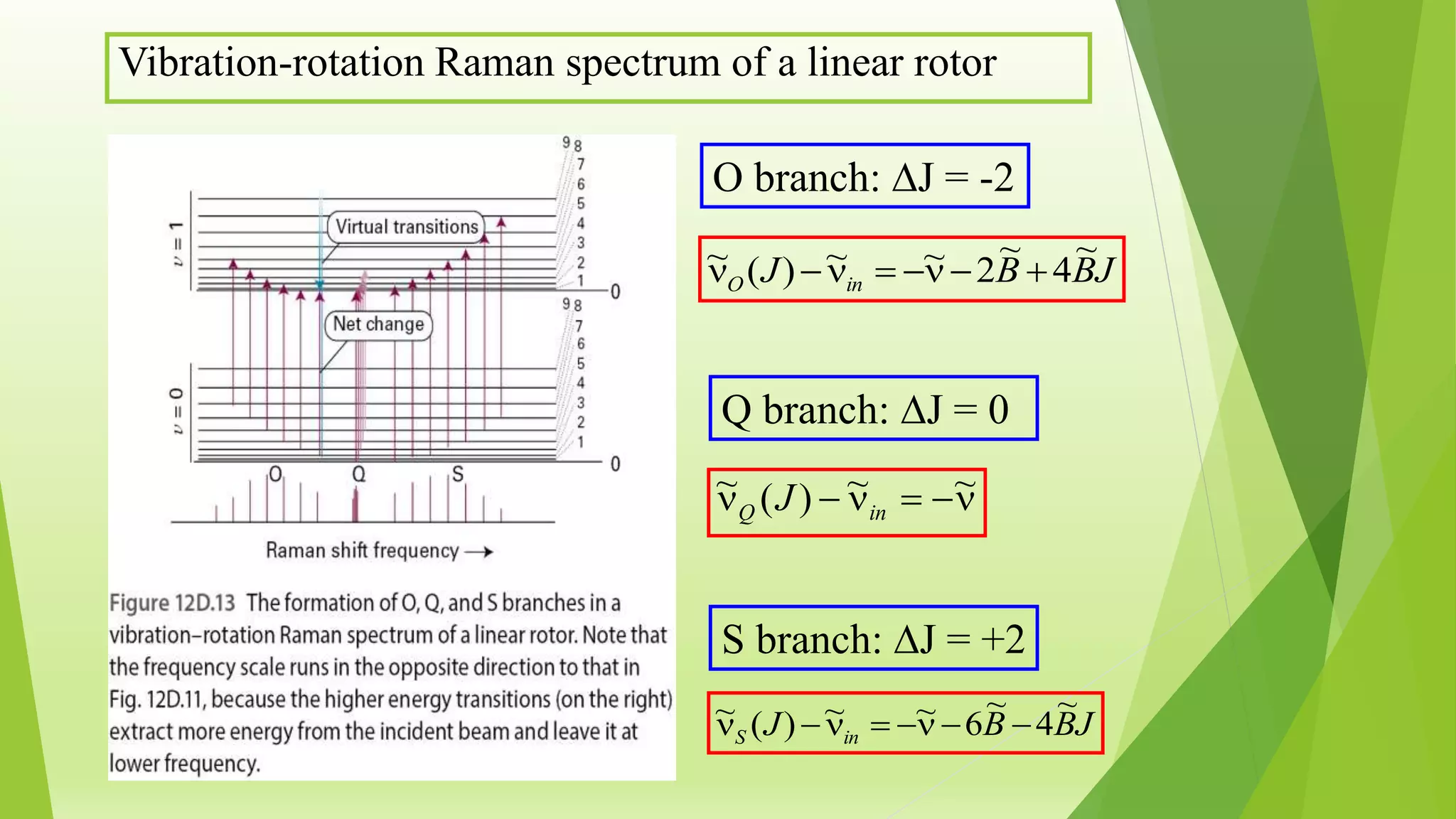

Raman spectroscopy analyzes the scattering of monochromatic light when it interacts with molecular vibrations or rotations. It can provide information about molecular structure. When light interacts with a molecule, the light may be scattered at the same frequency (Rayleigh scattering) or at a shifted lower (Stokes) or higher (anti-Stokes) frequency, depending on whether the molecule gains or loses vibrational or rotational energy. Selection rules determine which molecular motions are observable by Raman spectroscopy. Rotational Raman spectra of linear molecules exhibit a characteristic pattern depending on the change in rotational quantum number.