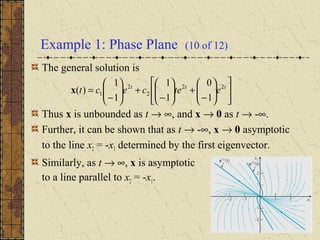

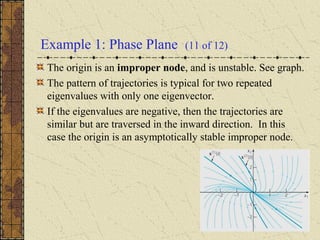

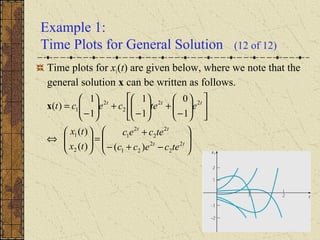

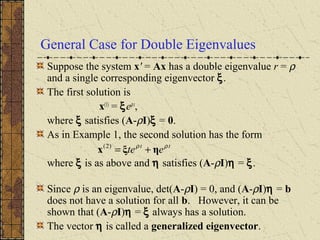

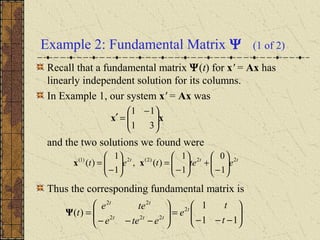

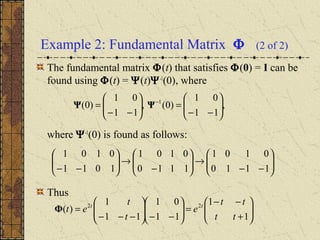

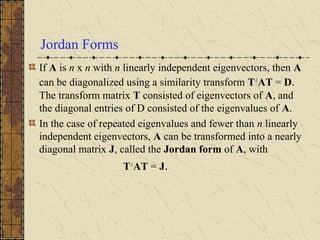

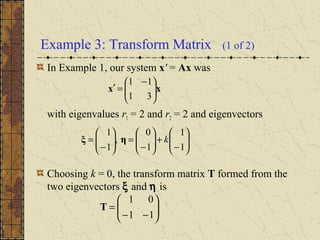

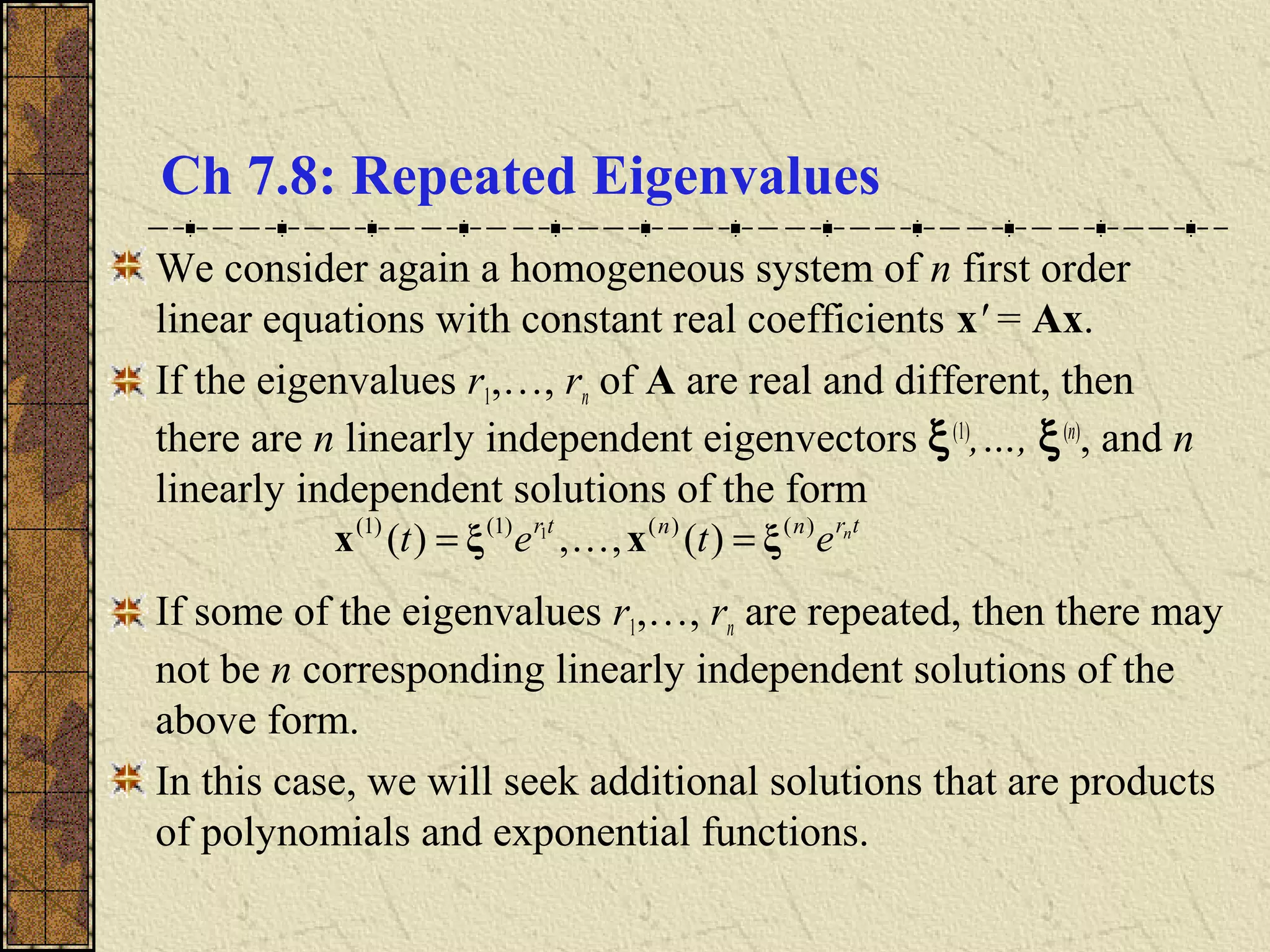

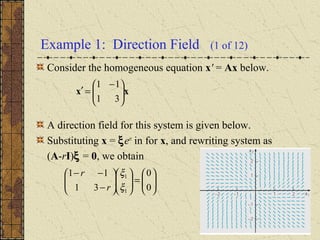

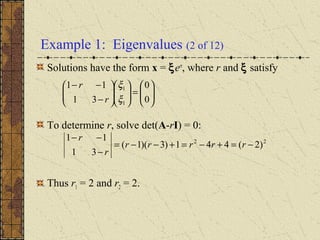

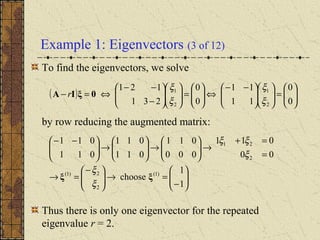

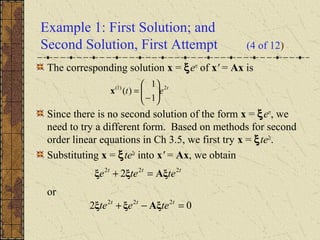

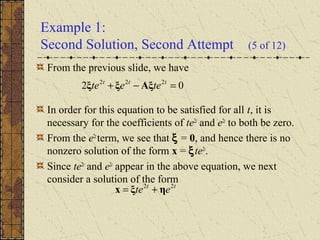

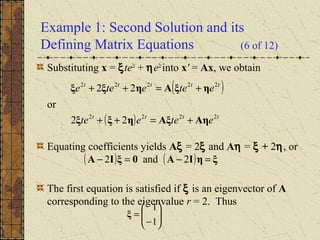

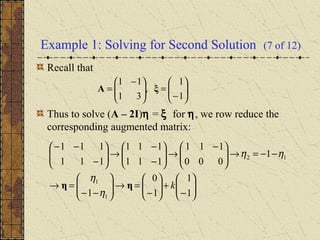

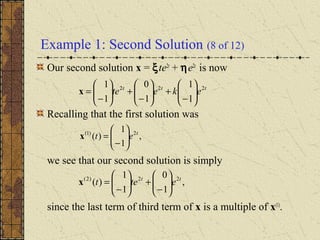

The document discusses repeated eigenvalues in systems of linear differential equations. If some eigenvalues are repeated, there may not be n linearly independent solutions of the form x = ξert. Additional solutions must be sought that are products of polynomials and exponential functions. For a double eigenvalue r, the first solution is x(1) = ξert, where ξ satisfies (A-rI)ξ = 0. The second solution has the form x(2) = ξtert + ηert, where η satisfies (A-rI)η = ξ and η is called a generalized eigenvector.

![Example 1: General Solution (9 of 12)

The two solutions of x' = Ax are

The Wronskian of these two solutions is

Thus x(1)

and x(2)

are fundamental solutions, and the general

solution of x' = Ax is

[ ] 0)(, 4

222

22

)2()1(

≠−=

−−

= t

ttt

tt

e

etee

tee

tW xx

−

+

−

+

−

=

+=

ttt

etecec

tctct

22

2

2

1

)2(

2

)1(

1

1

0

1

1

1

1

)()()( xxx

ttt

etetet 22)2(2)1(

1

0

1

1

)(,

1

1

)(

−

+

−

=

−

= xx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch078-150731094838-lva1-app6891/85/Ch07-8-10-320.jpg)