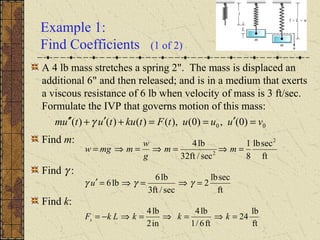

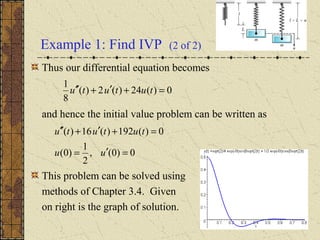

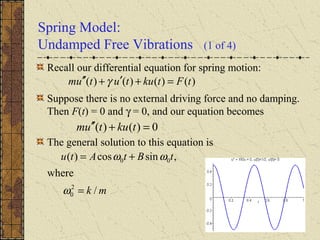

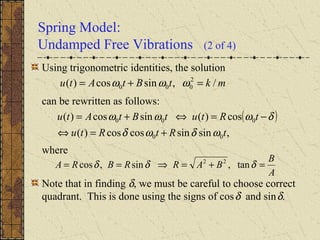

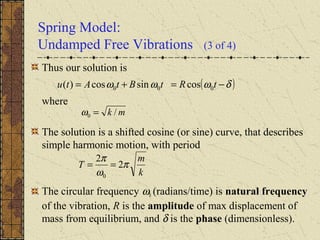

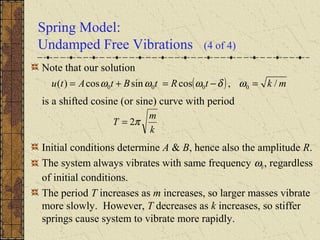

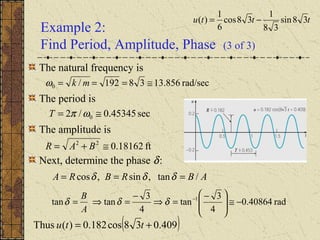

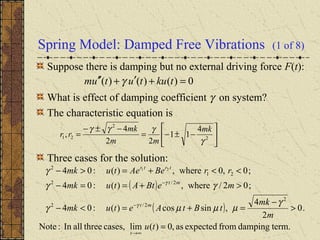

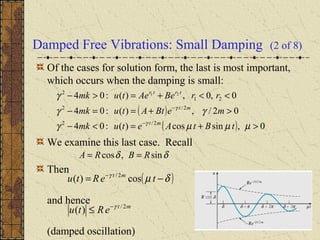

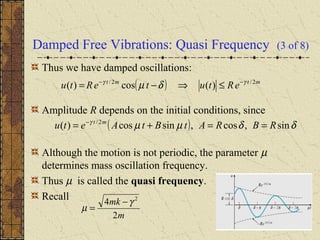

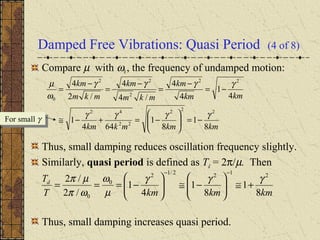

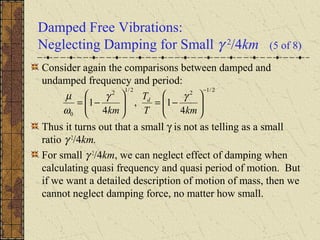

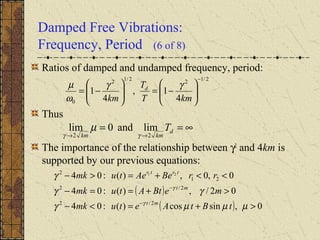

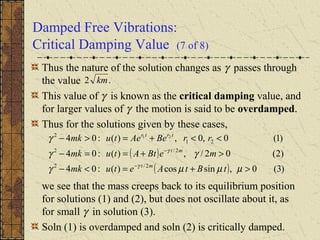

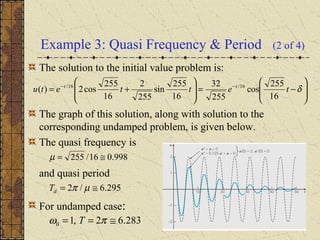

The motion of a mass attached to a spring can be modeled by a second order differential equation. For undamped free vibrations with no external force, the solution is a simple harmonic motion with natural frequency ω0 and period T. Small damping causes the motion to be damped oscillations with slightly reduced quasi-frequency μ and increased quasi-period Td. The ratio γ2/4km determines whether damping can be neglected - if small, damping has little effect on frequency and period.

![Spring Model:

Spring Force Details

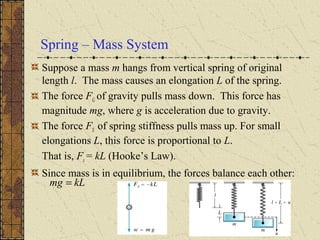

The spring force Fs acts to restore spring to natural position,

and is proportional to L + u. If L + u > 0, then spring is

extended and the spring force acts upward. In this case

If L + u < 0, then spring is compressed a distance of |L + u|,

and the spring force acts downward. In this case

In either case,

)( uLkFs +−=

( )[ ] ( )uLkuLkuLkFs +−=+−=+=

)( uLkFs +−=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch038-150731094636-lva1-app6891/85/Ch03-8-4-320.jpg)

![Spring Model:

Differential Equation

Taking into account these forces, Newton’s Law becomes:

Recalling that mg = kL, this equation reduces to

where the constants m, γ, and k are positive.

We can prescribe initial conditions also:

It follows from Theorem 3.2.1 that there is a unique solution

to this initial value problem. Physically, if mass is set in

motion with a given initial displacement and velocity, then

its position is uniquely determined at all future times.

[ ] )()()(

)()()()(

tFtutuLkmg

tFtFtFmgtum ds

+′−+−=

+++=′′

γ

)()()()( tFtkututum =+′+′′ γ

00 )0(,)0( vuuu =′=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch038-150731094636-lva1-app6891/85/Ch03-8-6-320.jpg)