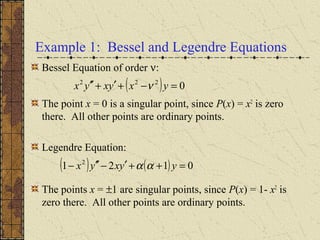

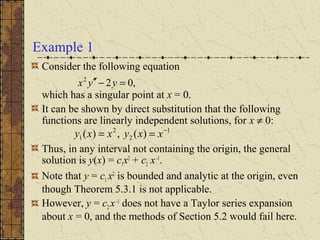

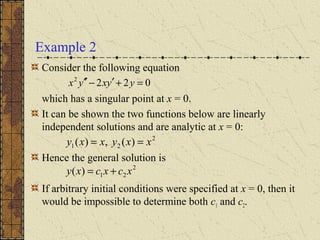

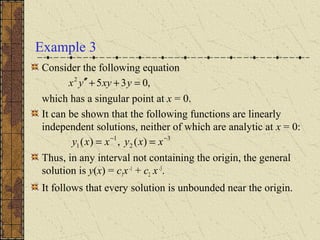

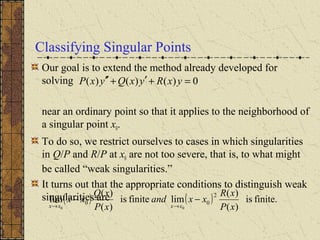

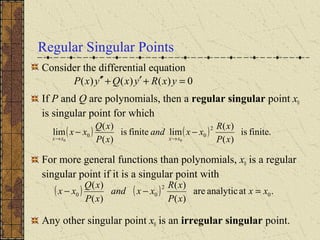

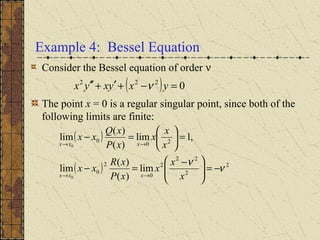

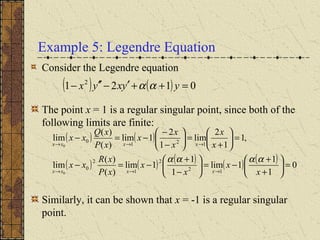

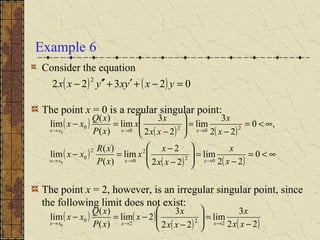

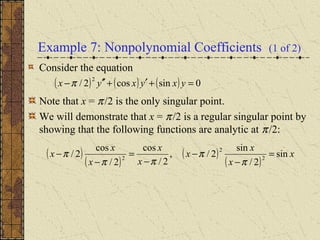

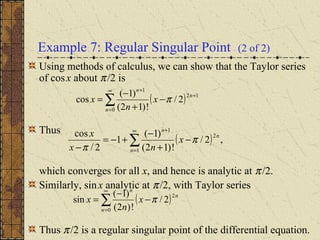

The document discusses regular singular points of differential equations. A point x0 is a regular singular point if the functions P, Q, and R are analytic at x0 or their limits exist and are finite as x approaches x0. Several examples are provided to illustrate regular singular points, including the Bessel and Legendre equations. An irregular singular point is defined as one where these limits do not exist. The behavior of solutions near regular singular points can be analyzed using power series methods.