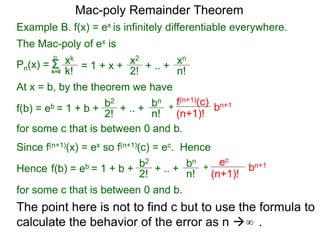

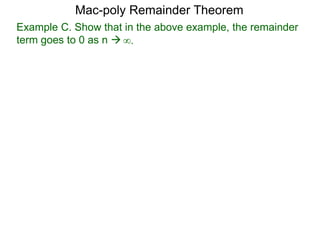

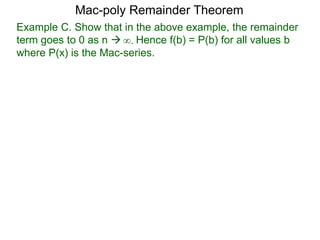

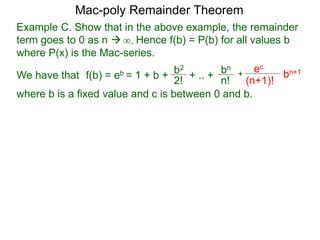

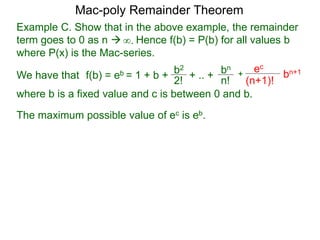

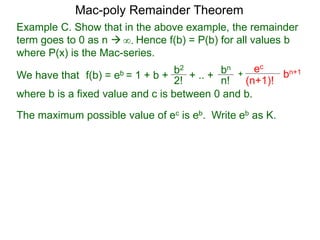

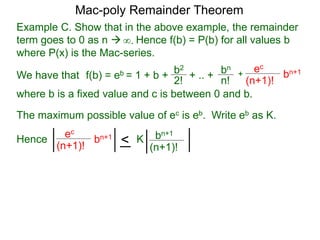

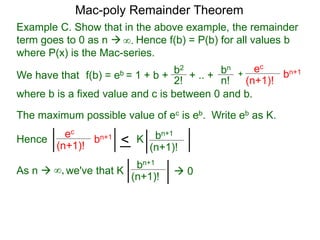

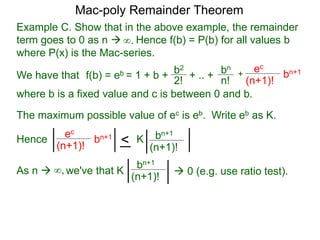

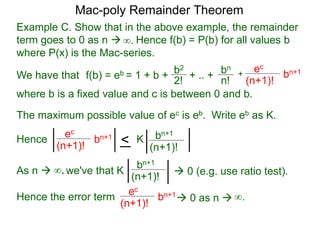

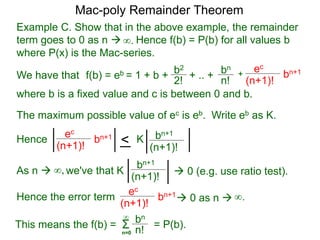

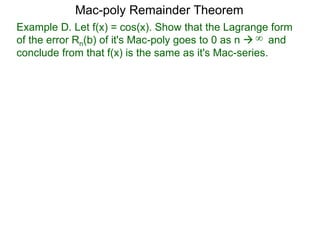

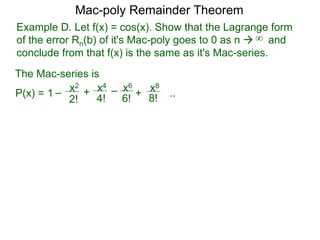

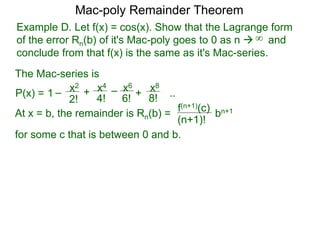

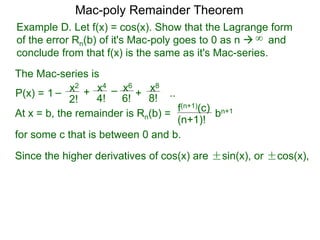

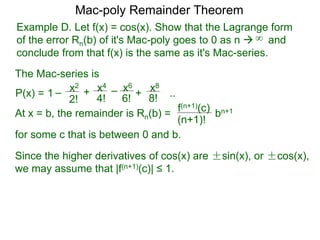

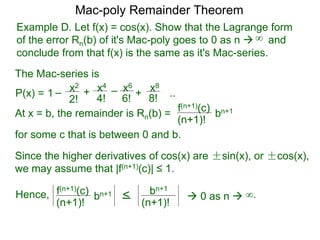

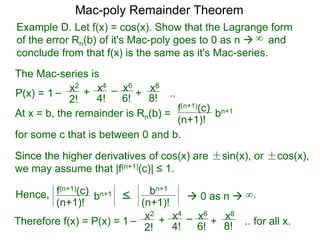

The document discusses the Mac-poly Remainder Theorem, which provides a formula for the difference between a function value f(b) and its nth Mac-poly polynomial value pn(b). Specifically:

- The theorem states that for a function f(x) that is infinitely differentiable over an interval containing [0,b], there exists a c between b and 0 such that f(b) = pn(b) + Rn(b), where Rn(b) is the remainder term involving the (n+1)th derivative of f.

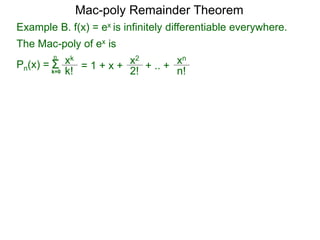

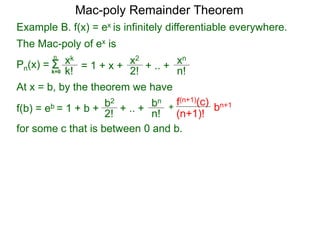

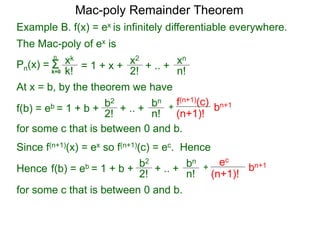

- An example shows applying the theorem to the function f(x)=ex, finding the Mac-poly is the series 1 + x +

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

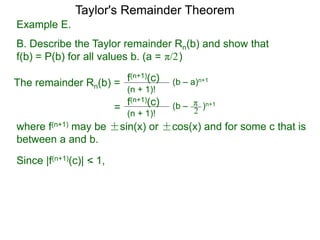

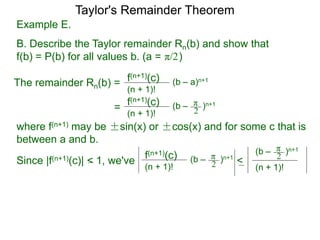

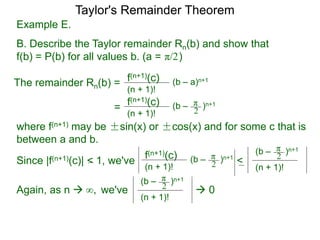

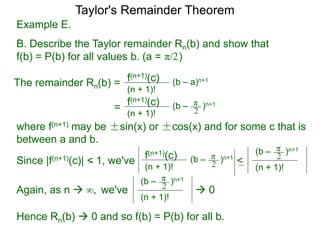

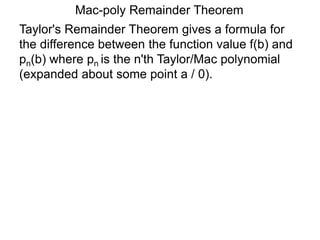

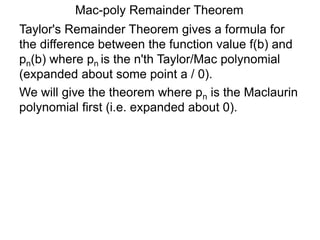

Taylor's Remainder Theorem gives a formula for

the difference between the function value f(b) and

pn(b) where pn is the n'th Taylor/Mac polynomial

(expanded about some point a / 0).

We will give the theorem where pn is the Maclaurin

polynomial first (i.e. expanded about 0).

Mac-poly Remainder Theorem: Let f(x) be an infinitely

differentiable function over an open interval that

contains [0, b] and pn(x) be its n'th Mac-poly,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-12-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

Taylor's Remainder Theorem gives a formula for

the difference between the function value f(b) and

pn(b) where pn is the n'th Taylor/Mac polynomial

(expanded about some point a / 0).

We will give the theorem where pn is the Maclaurin

polynomial first (i.e. expanded about 0).

0

( )[ ]

b

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here

Mac-poly Remainder Theorem: Let f(x) be an infinitely

differentiable function over an open interval that

contains [0, b] and pn(x) be its n'th Mac-poly,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-13-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

Mac-poly Remainder Theorem: Let f(x) be an infinitely

differentiable function over an open interval that

contains [0, b] and pn(x) be its n'th Mac-poly,

Taylor's Remainder Theorem gives a formula for

the difference between the function value f(b) and

pn(b) where pn is the n'th Taylor/Mac polynomial

(expanded about some point a / 0).

then there exists a "c" between b and 0

We will give the theorem where pn is the Maclaurin

polynomial first (i.e. expanded about 0).

0

( )[ ]

bc

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-14-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

Mac-poly Remainder Theorem: Let f(x) be an infinitely

differentiable function over an open interval that

contains [0, b] and pn(x) be its n'th Mac-poly,

Taylor's Remainder Theorem gives a formula for

the difference between the function value f(b) and

pn(b) where pn is the n'th Taylor/Mac polynomial

(expanded about some point a / 0).

then there exists a "c" between b and 0 such that

f(b) = pn(b) +

We will give the theorem where pn is the Maclaurin

polynomial first (i.e. expanded about 0).

bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0

( )[ ]

bc

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-15-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

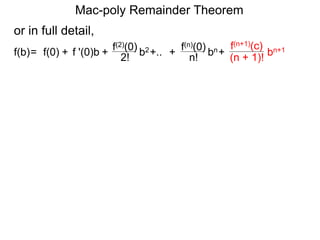

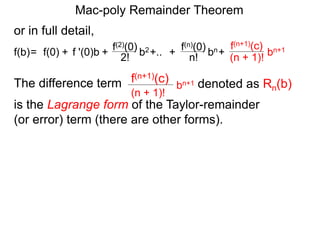

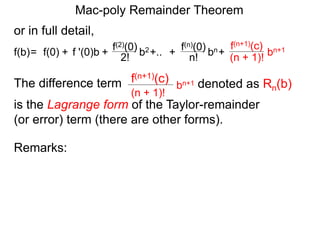

or in full detail,

The difference term denoted as Rn(b)bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder

(or error) term (there are other forms).

f '(0)b f(2)(0)

+ 2!= f(0) + b2f(b) +.. f(n)(0)

n! bn+ bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

+

Remarks:

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, 0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-19-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

or in full detail,

The difference term denoted as Rn(b)bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder

(or error) term (there are other forms).

f '(0)b f(2)(0)

+ 2!= f(0) + b2f(b) +.. f(n)(0)

n! bn+ bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

+

Remarks:

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, 0]

* the value c changes if the value of b or n changes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-20-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

or in full detail,

The difference term denoted as Rn(b)bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder

(or error) term (there are other forms).

f '(0)b f(2)(0)

+ 2!= f(0) + b2f(b) +.. f(n)(0)

n! bn+ bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

+

Remarks:

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, 0]

* the value c can't be easily determined, we just know

there is at least one c that fits the description

* the value c changes if the value of b or n changes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-21-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

We state the following theorem.

Theorem: Given f(x), and [0, b] as in the Mac-poly

Remainder theorem. Let P(x) be the Mac-series of

f(x), then f(b) = P(b) if and only if the error term

Rn(b) = bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0 as n ∞.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-38-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

We state the following theorem.

(reminder: c is not fixed, it changes as n changes.)

Theorem: Given f(x), and [0, b] as in the Mac-poly

Remainder theorem. Let P(x) be the Mac-series of

f(x), then f(b) = P(b) if and only if the error term

Rn(b) = bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0 as n ∞.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-39-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

We state the following theorem.

(reminder: c is not fixed, it changes as n changes.)

Theorem: Given f(x), and [0, b] as in the Mac-poly

Remainder theorem. Let P(x) be the Mac-series of

f(x), then f(b) = P(b) if and only if the error term

Rn(b) = bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0 as n ∞.

A function that is equal to its Mac-series over an

open interval around 0 is said to be analytic at 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-40-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

We state the following theorem.

(reminder: c is not fixed, it changes as n changes.)

Theorem: Given f(x), and [0, b] as in the Mac-poly

Remainder theorem. Let P(x) be the Mac-series of

f(x), then f(b) = P(b) if and only if the error term

Rn(b) = bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0 as n ∞.

A function that is equal to its Mac-series over an

open interval around 0 is said to be analytic at 0.

The function f(x) = ex is analytic at 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-41-320.jpg)

![Mac-poly Remainder Theorem

We state the following theorem.

(reminder: c is not fixed, it changes as n changes.)

Theorem: Given f(x), and [0, b] as in the Mac-poly

Remainder theorem. Let P(x) be the Mac-series of

f(x), then f(b) = P(b) if and only if the error term

Rn(b) = bn+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

0 as n ∞.

A function that is equal to its Mac-series over an

open interval around 0 is said to be analytic at 0.

The function f(x) = ex is analytic at 0.

The function

f(x) = {e-1/x2

if x = 0

0 if x = 0

is infinitely differentiable but not analytic at 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-42-320.jpg)

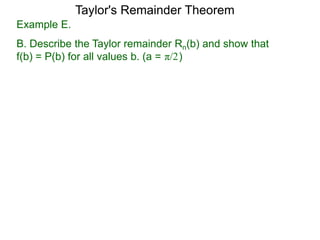

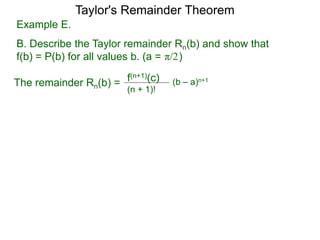

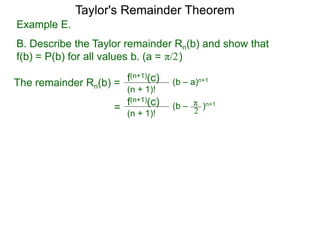

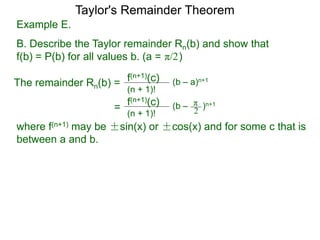

![Taylor's Remainder Theorem

We state the general form of the Taylor's remainder

formula.

Taylor's Remainder Theorem (General Form):

Let f(x) be an infinitely differentiable function over

some open interval that contains [a, b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-52-320.jpg)

![Taylor's Remainder Theorem

We state the general form of the Taylor's remainder

formula.

Taylor's Remainder Theorem (General Form):

Let f(x) be an infinitely differentiable function over

some open interval that contains [a, b]

a

( )[ ]

b

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-53-320.jpg)

![Taylor's Remainder Theorem

We state the general form of the Taylor's remainder

formula.

Taylor's Remainder Theorem (General Form):

Let f(x) be an infinitely differentiable function over

some open interval that contains [a, b] and

pn(x) =

be the n'th Taylor-poly expanded at a.

a

( )[ ]

b

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here

Σk=0

n

(x – a)k

k!

f(k)(a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-54-320.jpg)

![Taylor's Remainder Theorem

We state the general form of the Taylor's remainder

formula.

Taylor's Remainder Theorem (General Form):

Let f(x) be an infinitely differentiable function over

some open interval that contains [a, b] and

pn(x) =

be the n'th Taylor-poly expanded at a.

Then there exists a "c" between a and b such that

f(b) = pn(b) + (b – a)n+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

a

( )[ ]

bc

f(x) is infinitely differentiable in here

Σk=0

n

(x – a)k

k!

f(k)(a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-55-320.jpg)

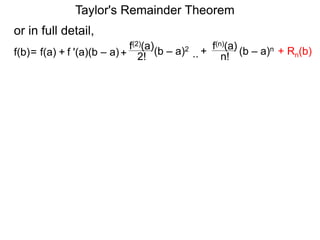

![or in full detail,

where Rn(b) = (b – a)n+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder.

f '(a)(b – a)

f(2)(a)

+ 2!= f(a) + (b – a)2

f(b) ..

f(n)(a)

n!

(b – a)n+

Again, we note the following

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, a]

Taylor's Remainder Theorem

+ Rn(b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-59-320.jpg)

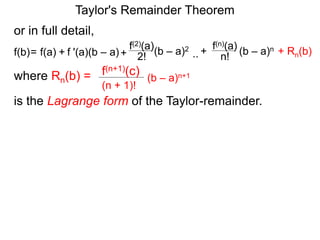

![or in full detail,

where Rn(b) = (b – a)n+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder.

f '(a)(b – a)

f(2)(a)

+ 2!= f(a) + (b – a)2

f(b) ..

f(n)(a)

n!

(b – a)n+

Again, we note the following

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, a]

* the value c changes if the value of b or n changes

Taylor's Remainder Theorem

+ Rn(b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-60-320.jpg)

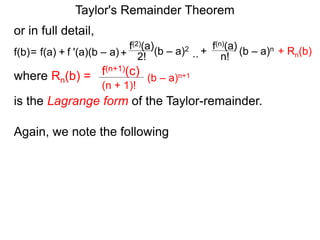

![or in full detail,

where Rn(b) = (b – a)n+1

(n + 1)!

f(n+1)(c)

is the Lagrange form of the Taylor-remainder.

f '(a)(b – a)

f(2)(a)

+ 2!= f(a) + (b – a)2

f(b) ..

f(n)(a)

n!

(b – a)n+

Again, we note the following

* the theorem also works for the interval [b, a]

* the value c can't be easily determined, we just know

there is at least one c that fits the description

* the value c changes if the value of b or n changes

Taylor's Remainder Theorem

+ Rn(b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/31mac-taylorremaindertheorem-x-190507215354/85/31-mac-taylor-remainder-theorem-x-61-320.jpg)