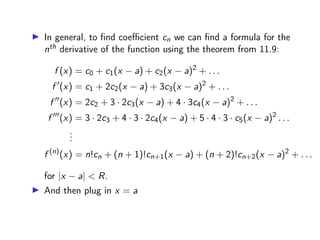

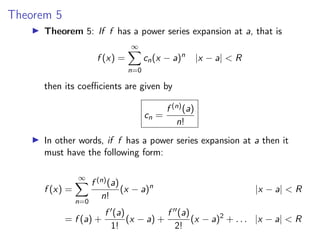

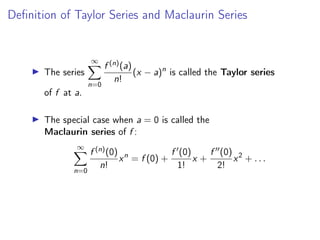

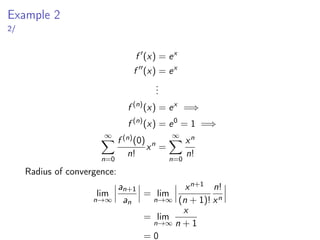

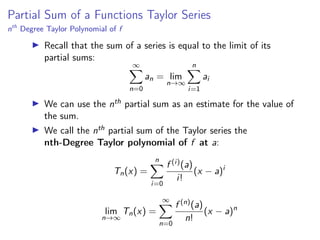

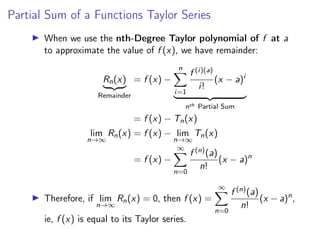

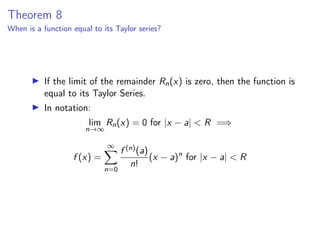

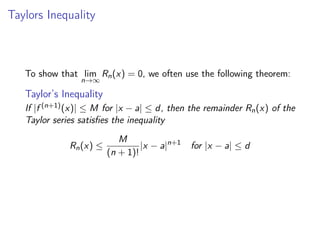

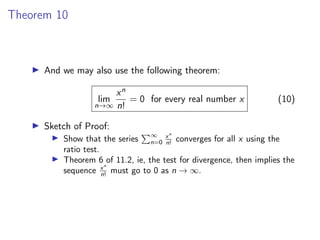

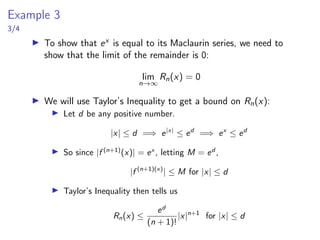

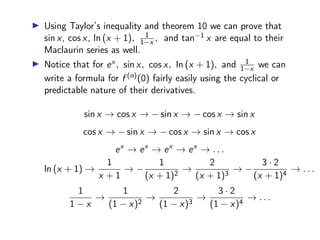

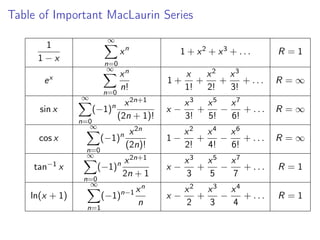

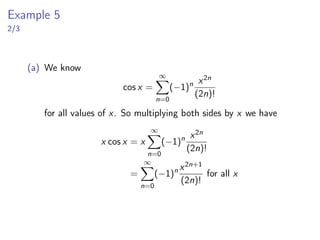

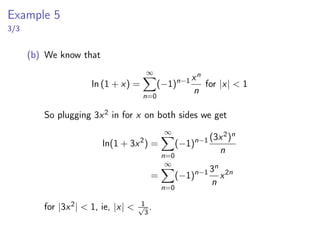

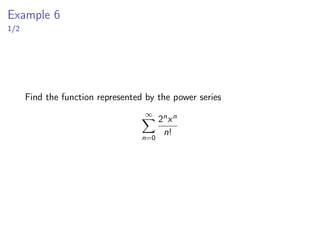

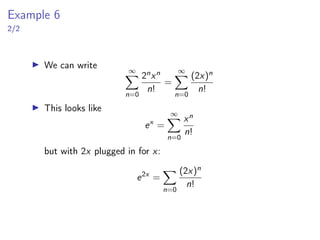

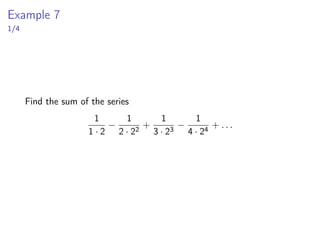

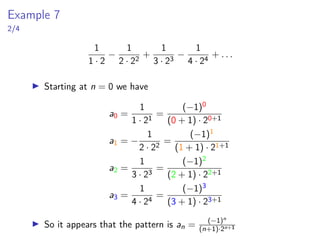

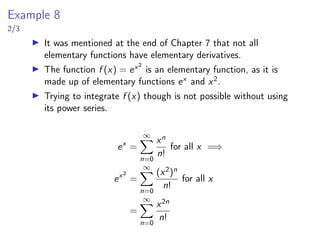

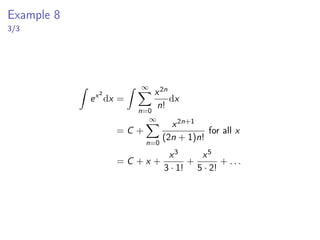

This document provides definitions and examples of Taylor and Maclaurin series. It defines Taylor series as the power series representation of a function f(x) centered at a, and Maclaurin series as the special case where a = 0. It describes how to compute the coefficients of the series by taking derivatives of f(x) and evaluating them at the center point a. Examples show how to derive Taylor/Maclaurin series for common functions like ex, sinx, and ln(x+1). The document also discusses when a function is equal to its Taylor series based on the limit of the remainder terms.