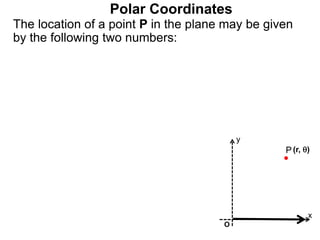

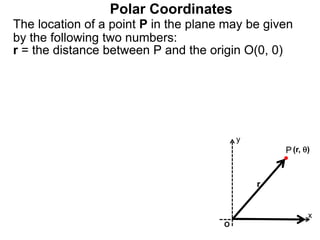

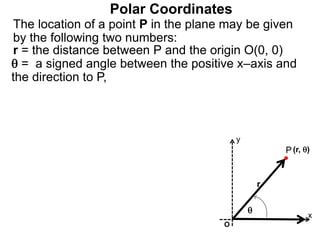

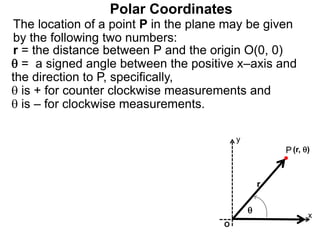

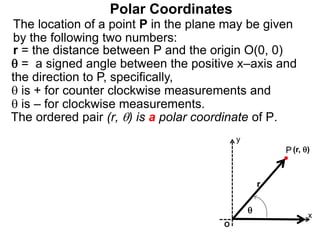

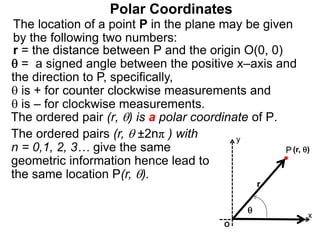

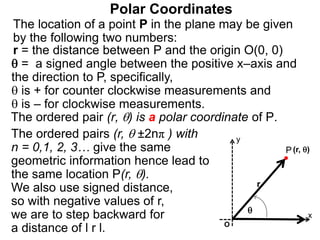

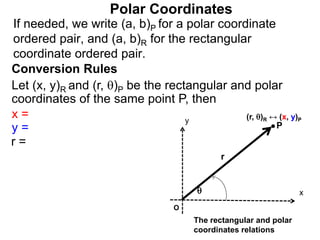

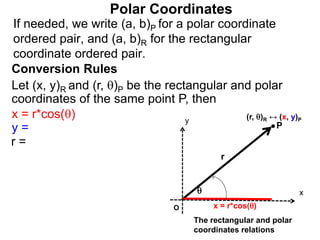

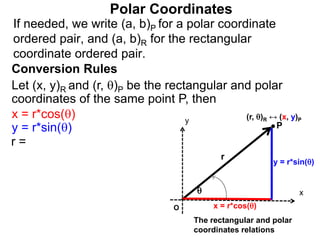

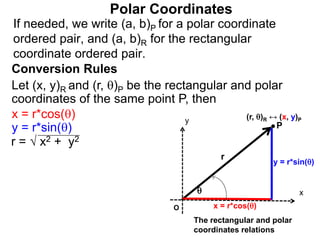

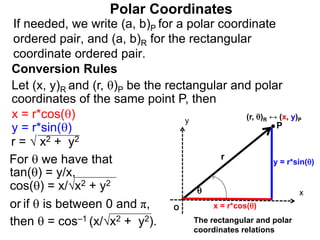

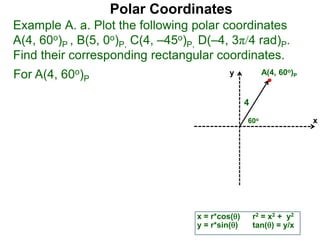

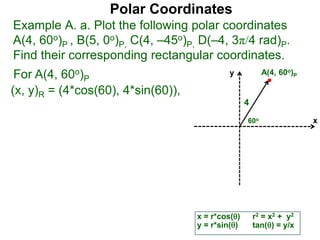

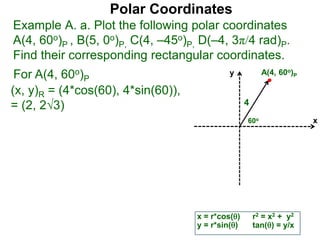

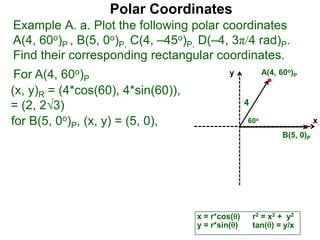

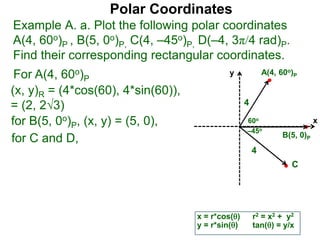

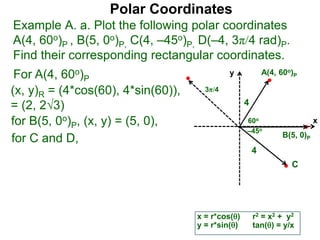

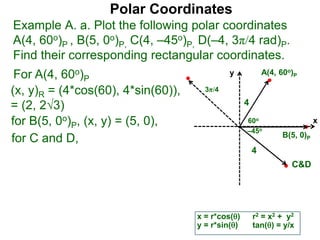

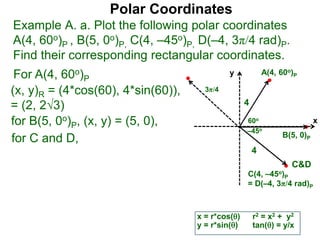

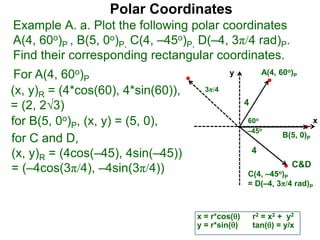

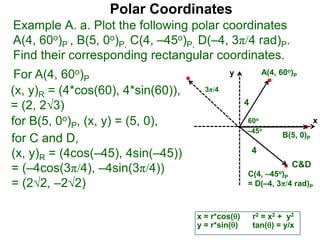

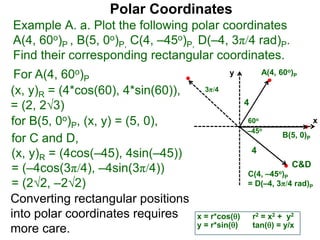

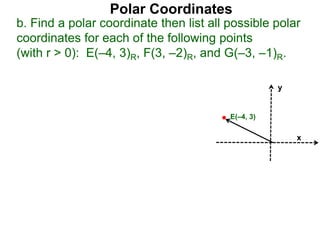

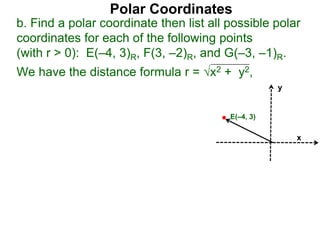

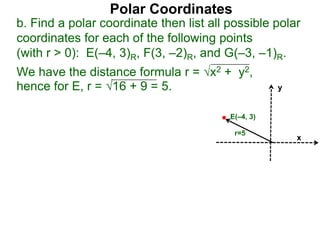

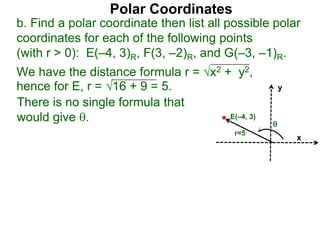

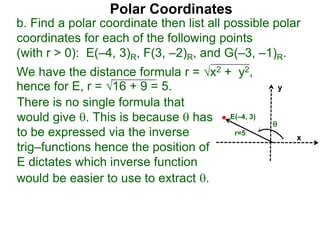

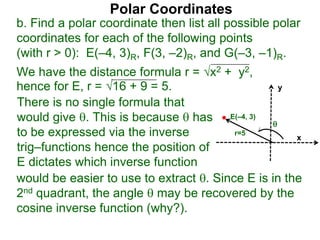

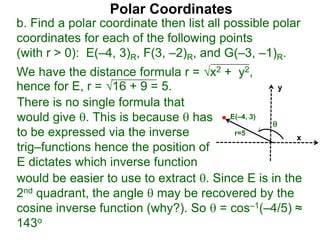

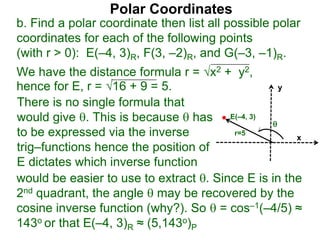

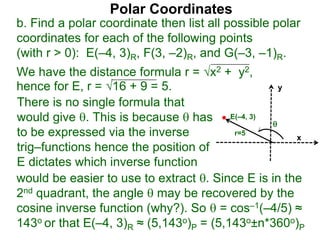

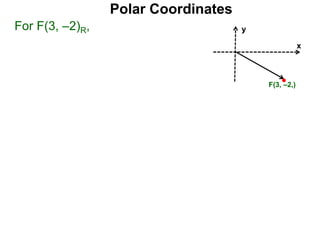

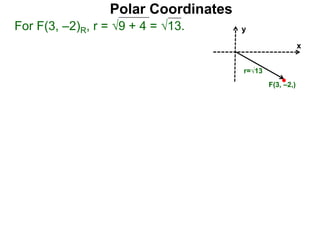

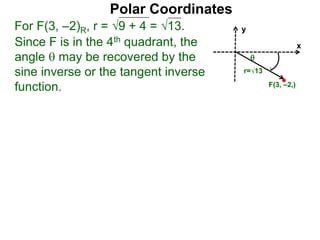

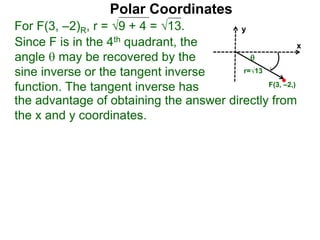

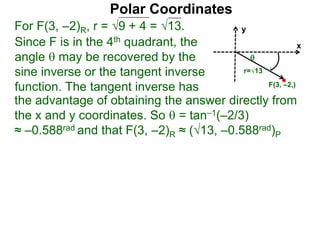

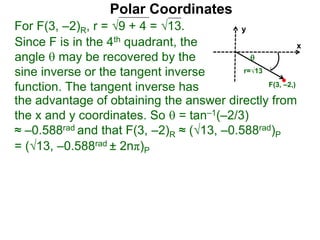

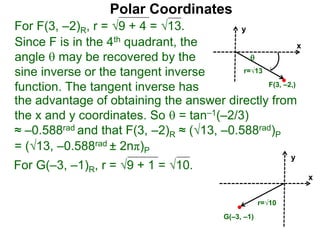

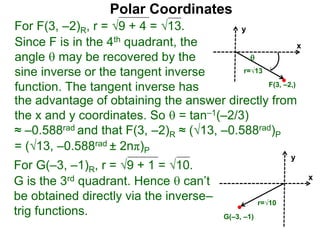

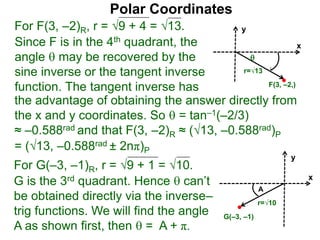

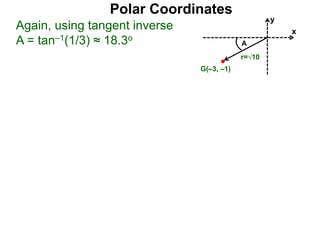

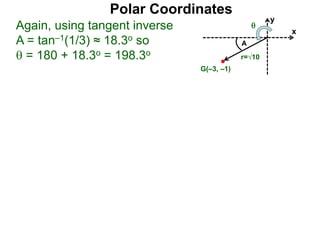

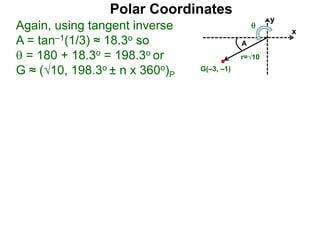

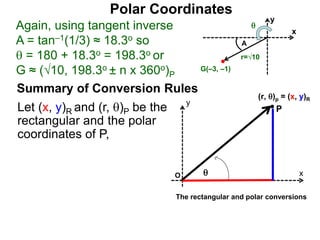

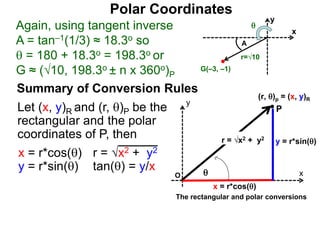

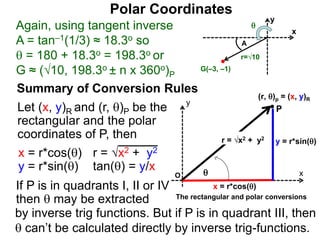

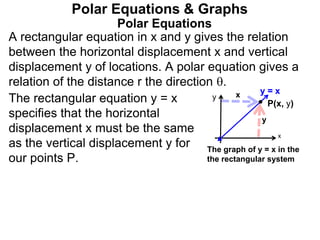

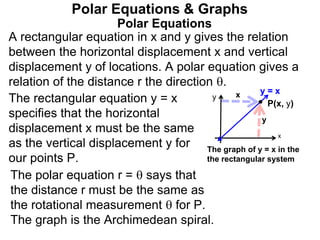

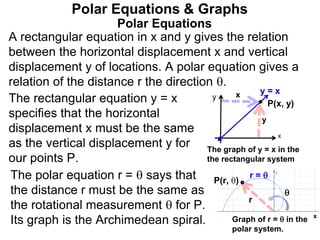

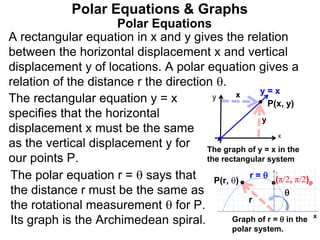

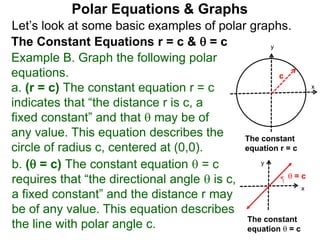

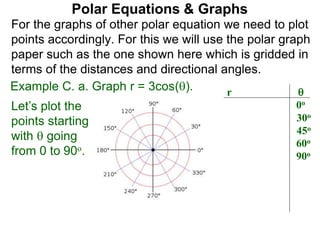

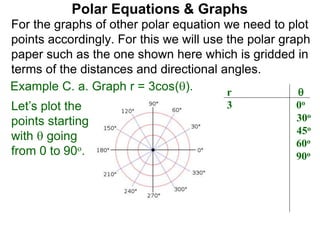

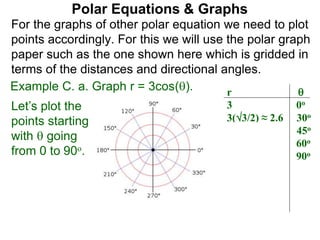

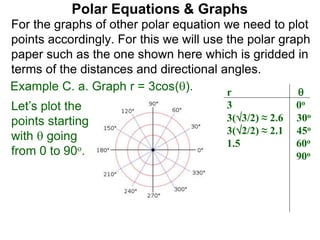

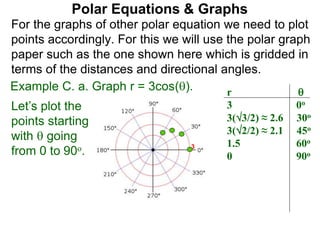

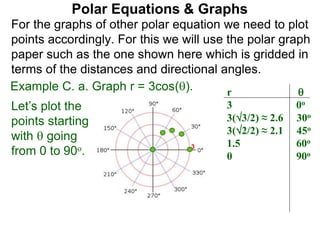

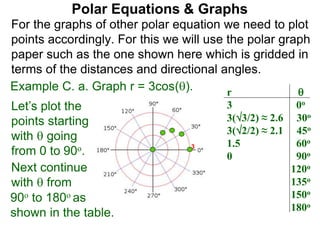

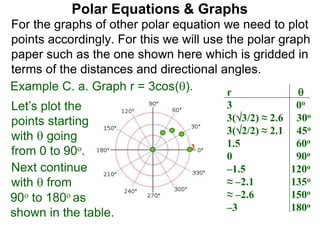

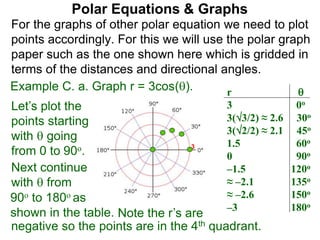

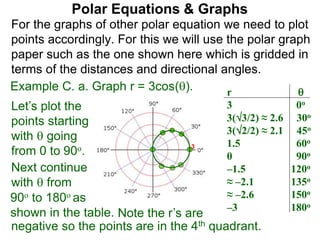

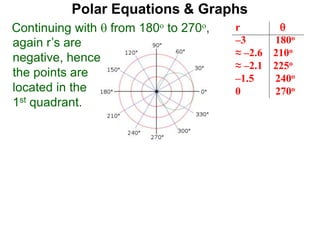

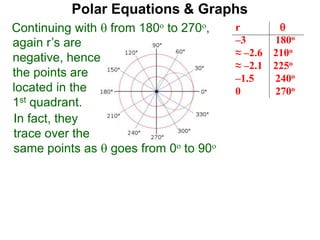

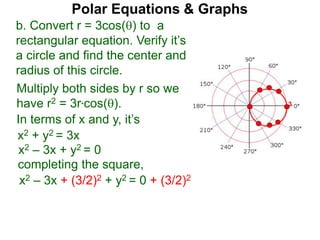

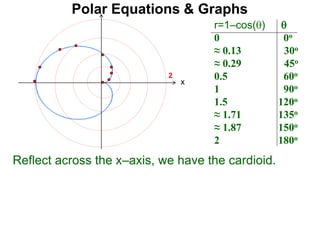

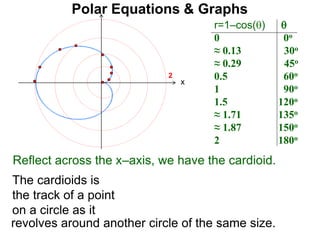

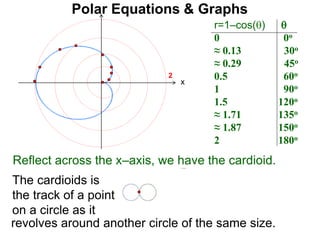

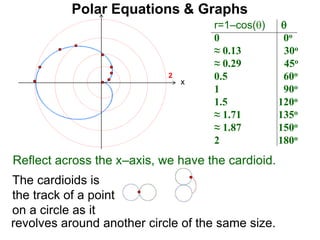

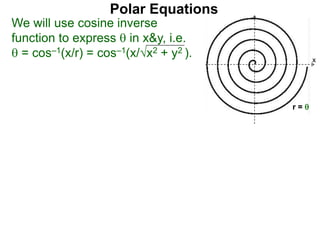

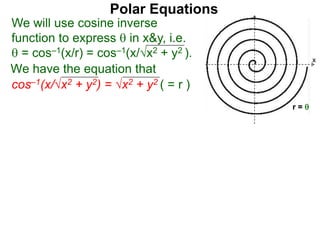

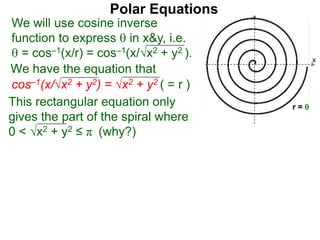

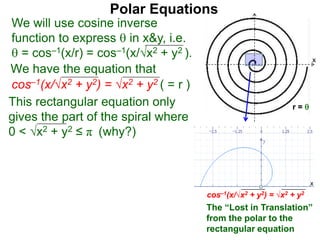

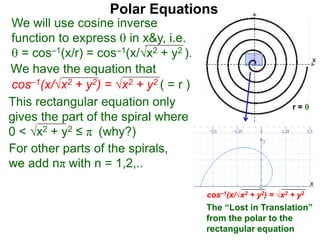

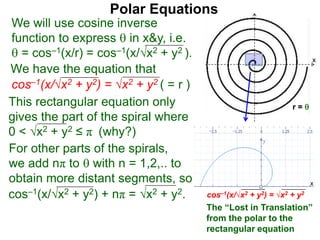

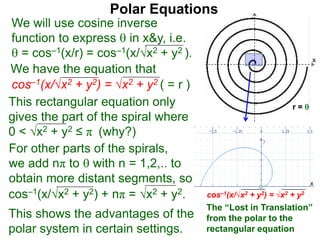

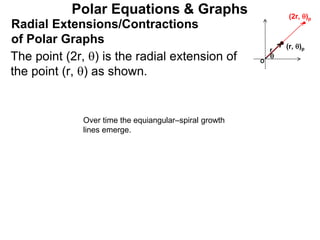

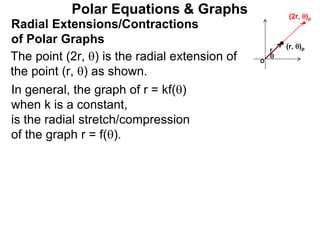

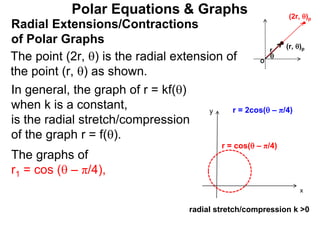

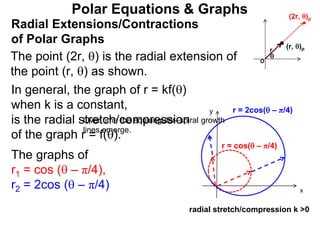

Polar coordinates provide an alternative way to specify the location of a point P in a plane using two numbers: r, the distance from P to the origin O, and θ, the angle between the x-axis and a line from O to P. θ is measured counter-clockwise from the x-axis and can be either positive or negative. A point P's polar coordinates (r, θ) uniquely identify its location. Polar and rectangular coordinates can be converted between each using the relationships x=r*cos(θ), y=r*sin(θ), and r=√(x2+y2).