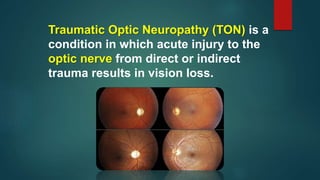

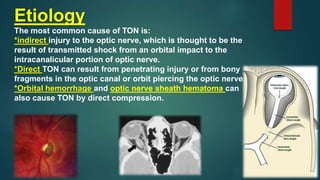

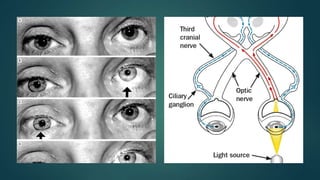

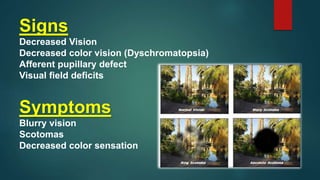

This document discusses traumatic optic neuropathy (TON), which is vision loss caused by direct or indirect injury to the optic nerve. Indirect injury is most common and thought to be caused by transmitted shock from an orbital impact. Risk factors are mostly male gender and ages around 34. Diagnosis is clinical based on vision symptoms and exam findings like visual field deficits. Management is controversial but corticosteroids and surgery have not been shown to improve outcomes compared to observation alone. Prognosis is generally poor with only around half of patients improving vision by 3 lines or more.