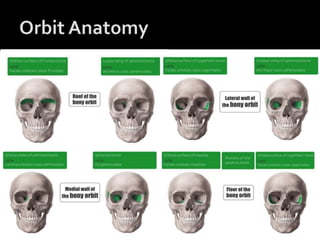

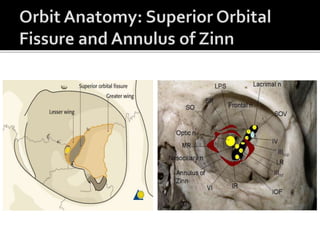

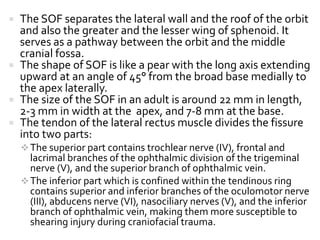

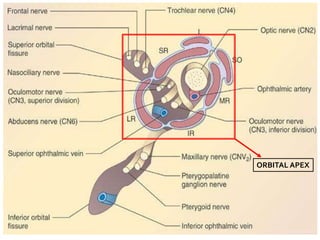

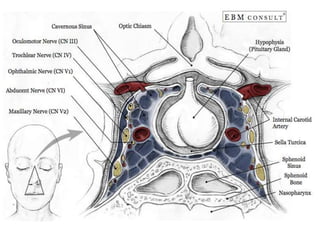

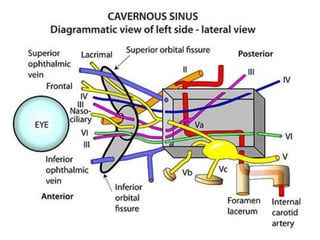

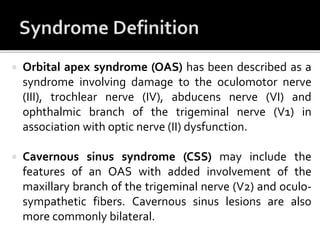

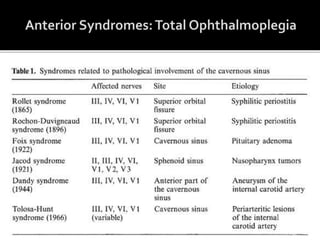

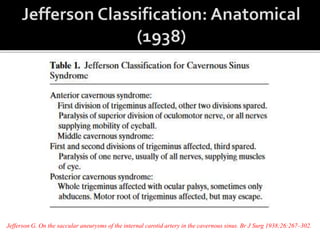

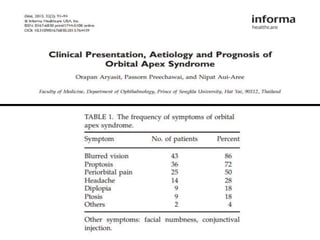

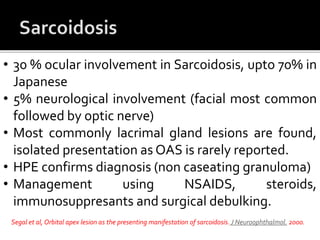

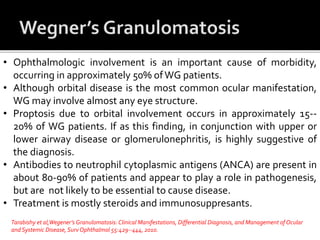

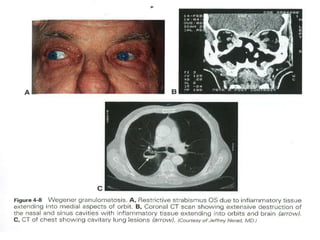

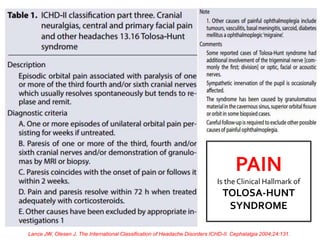

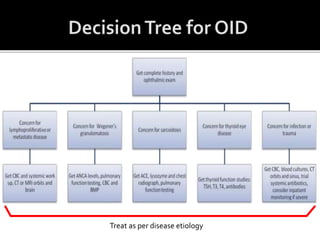

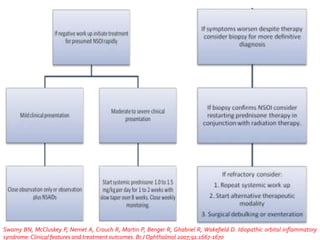

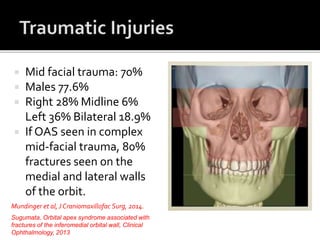

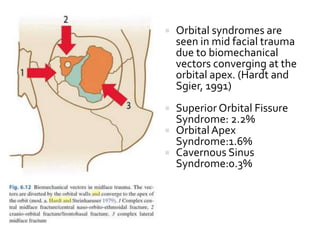

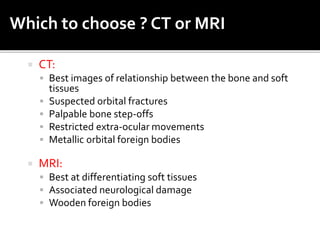

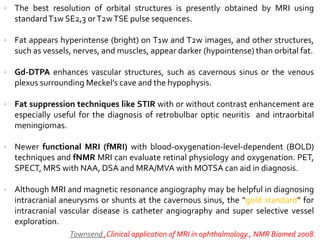

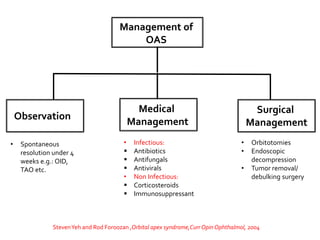

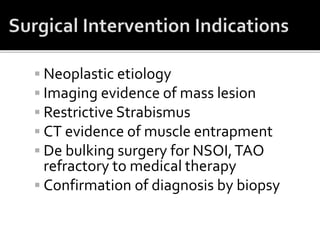

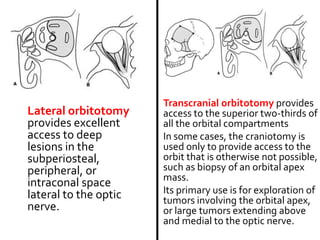

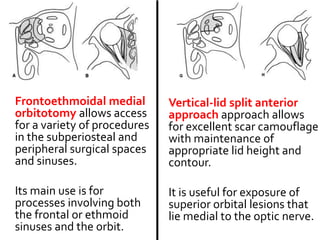

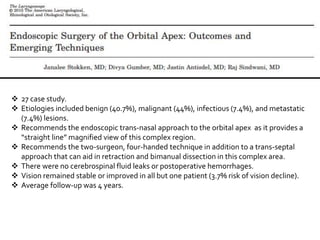

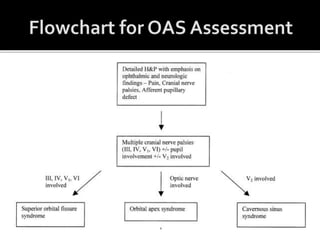

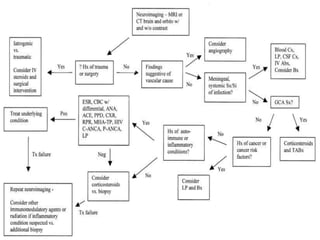

This document provides information on orbital apex syndrome (OAS) and related conditions. It begins with an overview of applied anatomy of the superior orbital fissure and orbital apex. It then discusses the classification of OAS, cavernous sinus syndrome, and superior orbital fissure syndrome. The clinical presentation, etiology, and management of these conditions is summarized. Common causes include tumors, infections, inflammation, and vascular abnormalities. The document provides details on specific pathologies, treatments, and outcomes.