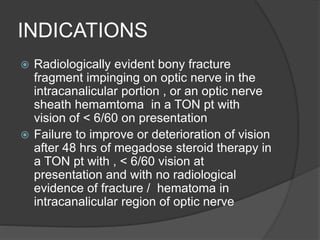

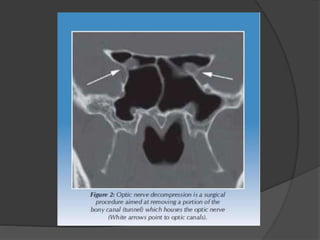

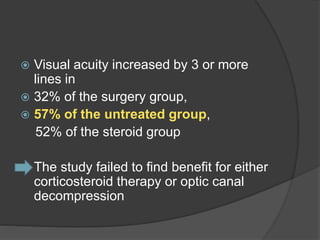

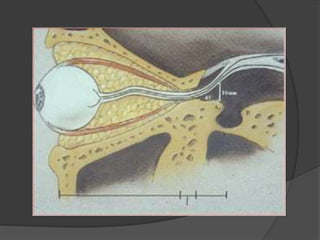

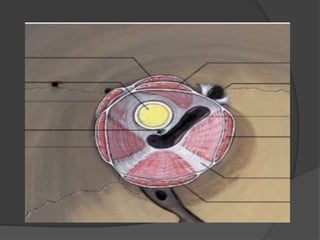

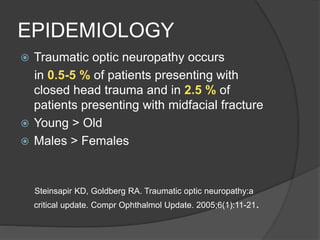

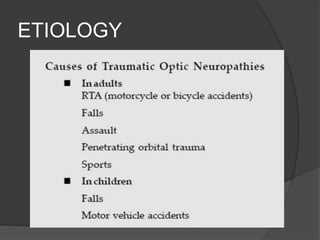

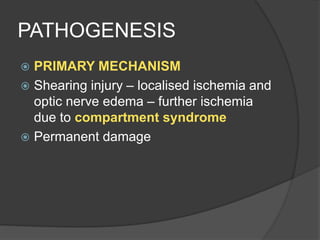

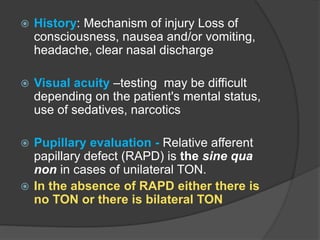

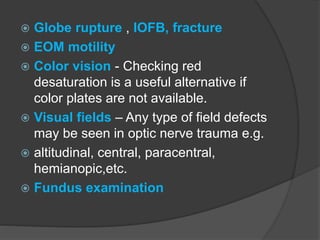

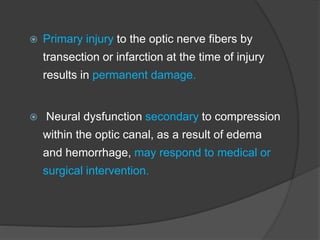

Traumatic optic neuropathy occurs when the optic nerve is injured from blunt force trauma anywhere along its path. While high-dose steroids and optic canal decompression surgery have been used as treatments, the evidence for their efficacy is limited. For non-transected injuries, observation is typically recommended, as primary damage to the optic nerve fibers is often permanent. Effective treatment options are extremely limited, and patients should be informed of the uncertainties regarding any proposed interventions.

![ National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study

2 [NASCIS II], a multicenter clinical trial

that evaluated patients with acute spinal

cord injury

In this study, patients were treated with

placebo,

methylprednisolone [MP],

or naloxone](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/traumaticopticneuropathy-150821152108-lva1-app6891/85/Traumatic-optic-neuropathy-33-320.jpg)