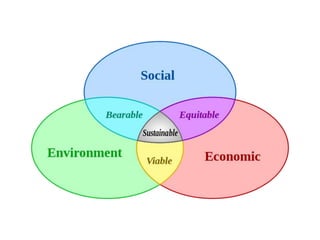

The document discusses the concept of sustainable development including its origins and implications. It begins by defining sustainability and tracing the key historical developments in conceptualizing sustainable development, from the 1972 Stockholm Conference to more recent climate agreements. It then outlines some initiatives in the sustainable development arena and ways of measuring sustainability through indicators. Finally, it discusses the relationship between development and ecology, highlighting perspectives from Hindu traditions that emphasize living in harmony with nature.

![Lynn White’s 1967 article

He says:

...[Christianity] not only established a dualism of

man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s

will that man exploit nature for his proper

ends… Man’s effective monopoly…was confirmed

and the old inhibitions to the exploitation of

nature crumbled… Christianity made it possible

to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the

feelings of natural objects.1

11/4/2016Dr. Varadraj Bapat, IIT Mumbai 13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sustainabledevelopmentmuapril2016-161104113550/85/Sustainable-development-2016-13-320.jpg)

![Lynn White’s 1967 article

He says:

White argued that '[Western] Christianity is the

most anthropocentric religion the world has

seen'.2 He concludes that the modern

technological conquest of nature that has led to

our environmental crisis has in large part been

made possible by the dominance in the West of

this Christian world-view. Christianity therefore

'bears a huge burden of guilt'.3

However, White does not think that secularism

is the answer to our environmental problems

11/4/2016Dr. Varadraj Bapat, IIT Mumbai 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sustainabledevelopmentmuapril2016-161104113550/85/Sustainable-development-2016-14-320.jpg)