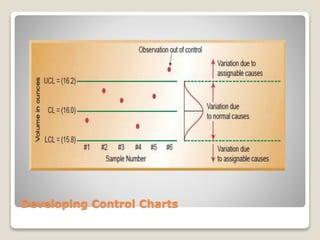

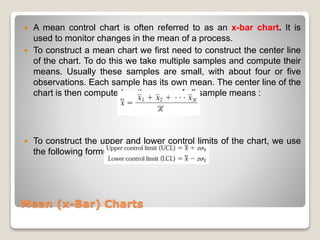

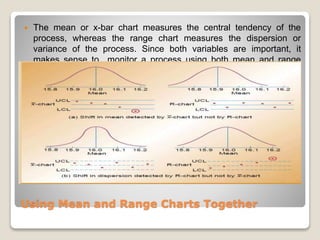

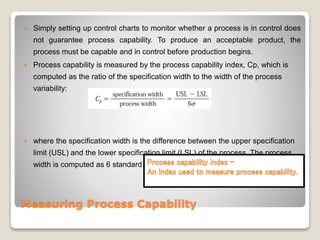

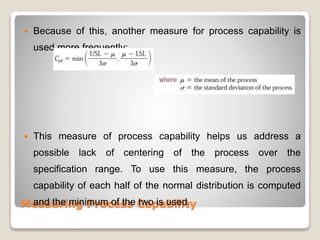

Statistical process control involves using statistical tools to monitor production processes and ensure quality. Descriptive statistics describe quality characteristics, while statistical process control uses techniques like control charts to determine if a process is producing products within a predetermined range. Control charts monitor processes over time, with samples plotted against control limits. If samples fall outside limits, it suggests the process is out of control. There are different types of control charts for variables that can be measured and attributes that can be counted. Monitoring processes with control charts helps distinguish common from assignable causes of variation.