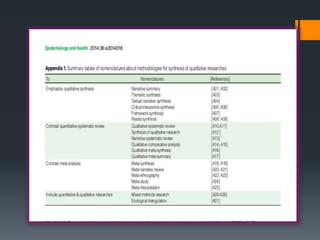

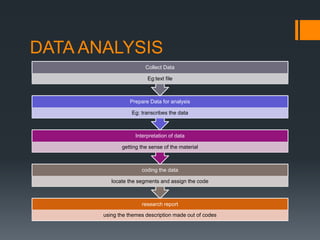

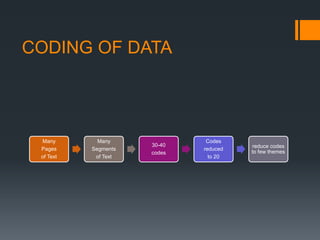

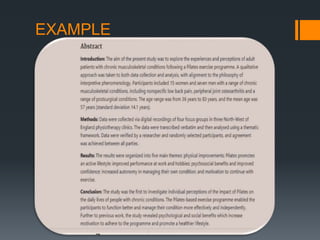

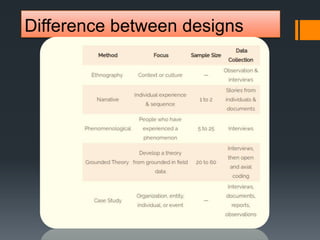

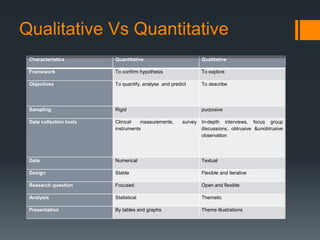

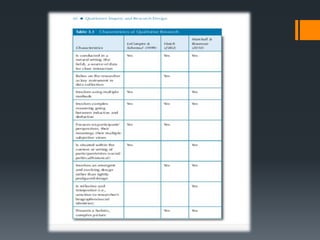

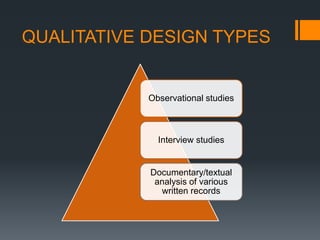

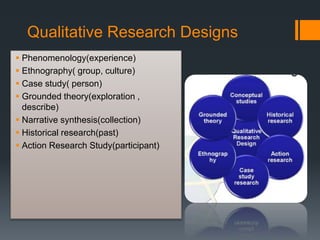

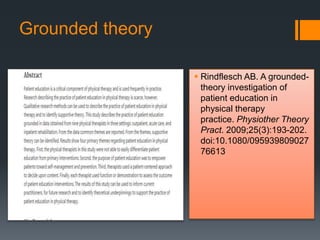

This document outlines the objectives and key aspects of qualitative research design. It discusses qualitative statement, types of qualitative designs including phenomenology, grounded theory, case study, narrative synthesis, ethnography, historical research and action research. It also covers sampling design, observational design, operational design, data analysis design and the differences between qualitative and quantitative designs. Key points covered include that qualitative research aims to understand and describe central experiences or processes for participants through methods like interviews and observations. Different qualitative designs have different focuses such as experiences for phenomenology or groups for ethnography. The document provides examples of studies for each design type.

![case study

Walker A, Boaz A, Hurley

MV. The role of leadership

in implementing and

sustaining an evidence-

based intervention for

osteoarthritis (ESCAPE-

pain) in NHS

physiotherapy services: a

qualitative case study

[published online ahead of

print, 2020 Aug 5]. Disabil

Rehabil. 2020;1-8.

doi:10.1080/09638288.20

20.1803997](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/qualitativeresearchdesign-210205141215/85/Qualitative-research-design-10-320.jpg)