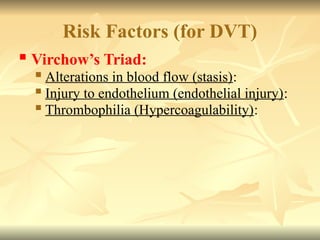

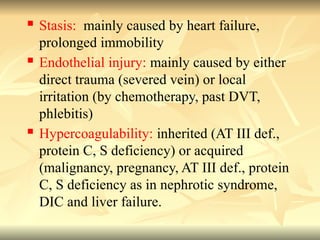

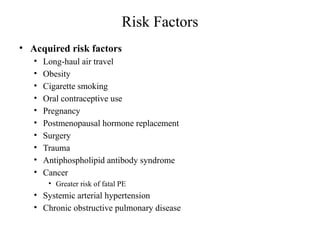

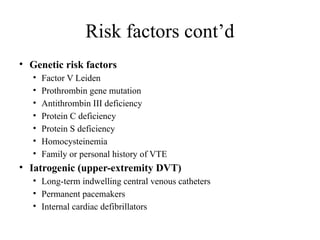

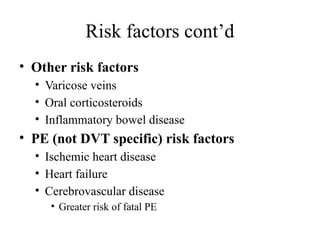

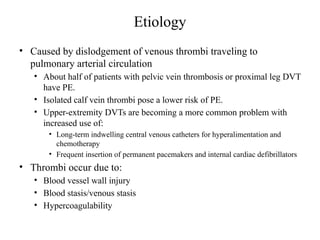

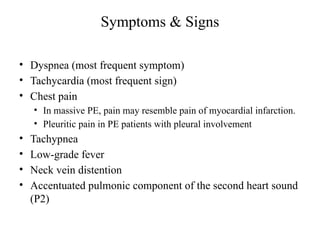

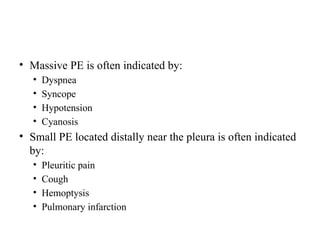

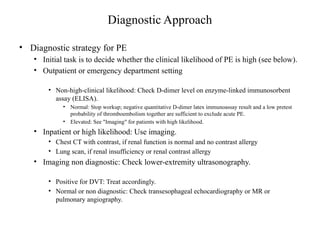

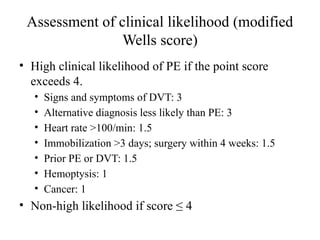

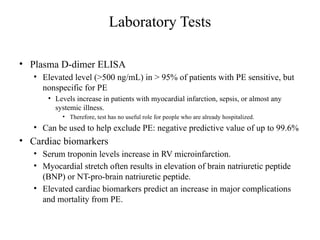

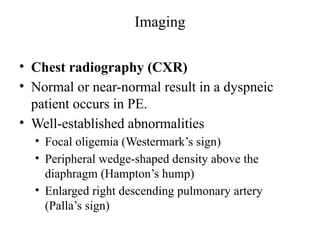

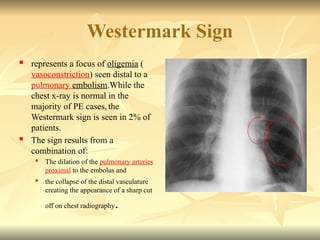

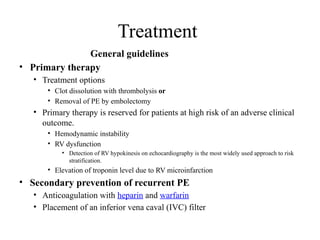

Pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when venous thrombi dislodge and block pulmonary arterial circulation, leading to various clinical syndromes. The incidence is about 69 cases per 100,000 annually, with multiple risk factors including advanced age, obesity, and certain medical conditions. Diagnosis involves a clinical likelihood assessment and imaging tests, while treatment typically includes anticoagulation and may require thrombolysis or embolectomy for high-risk patients.