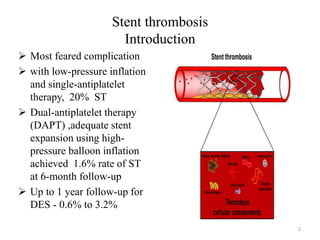

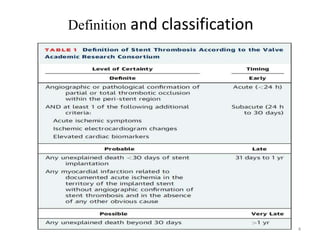

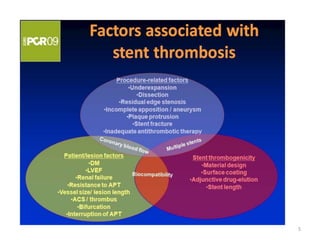

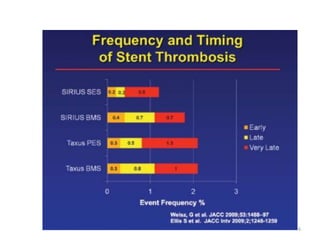

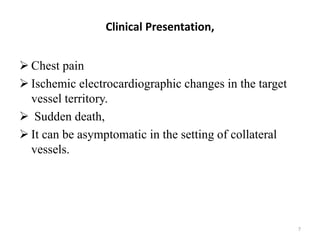

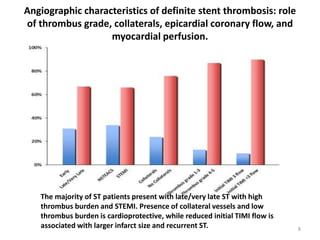

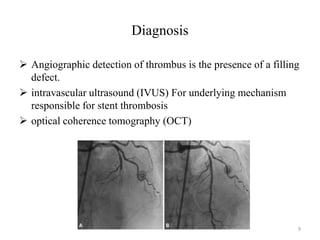

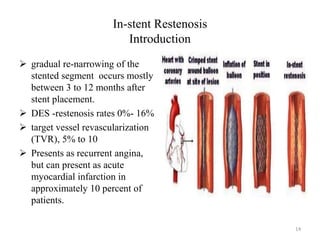

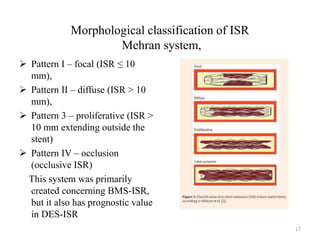

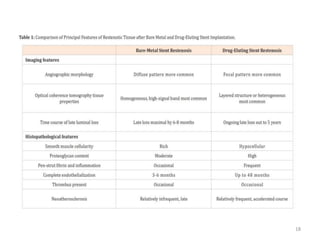

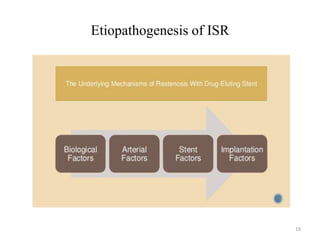

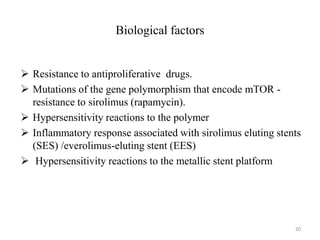

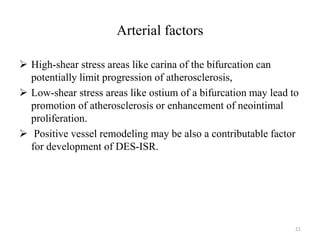

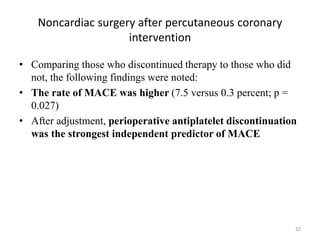

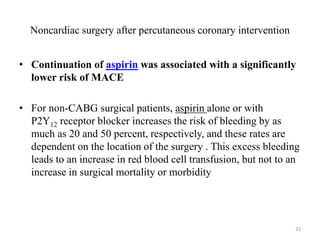

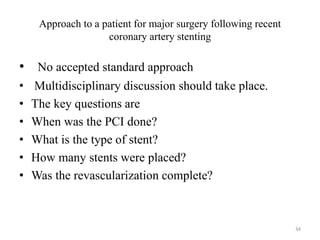

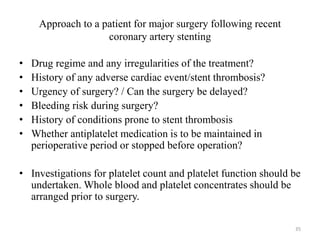

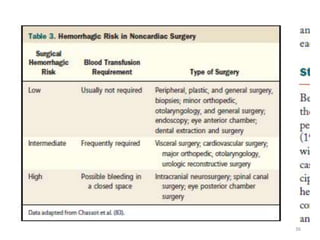

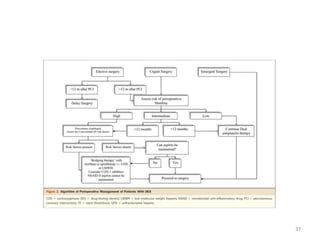

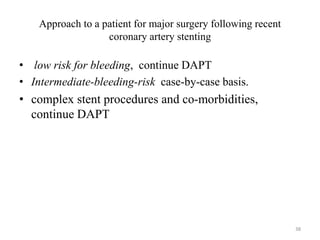

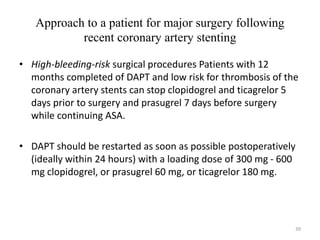

The document presents an overview of stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis associated with drug-eluting stents (DES), highlighting complications like stent thrombosis, its definitions, classifications, and mechanisms. It emphasizes the significance of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and discusses risks related to noncardiac surgery post-percutaneous coronary intervention. Key recommendations include managing DAPT in relation to surgical interventions based on bleeding risk and stent history.