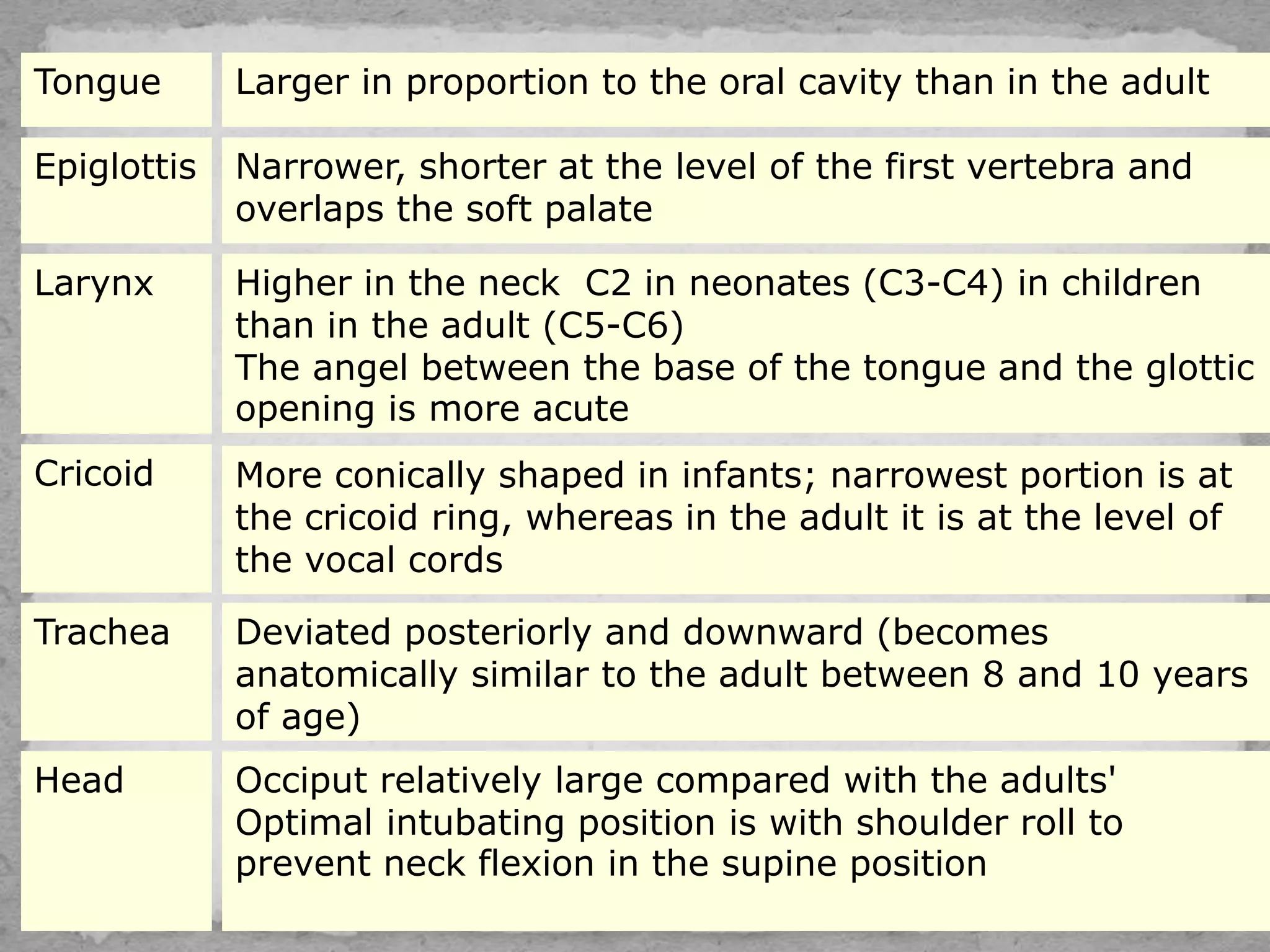

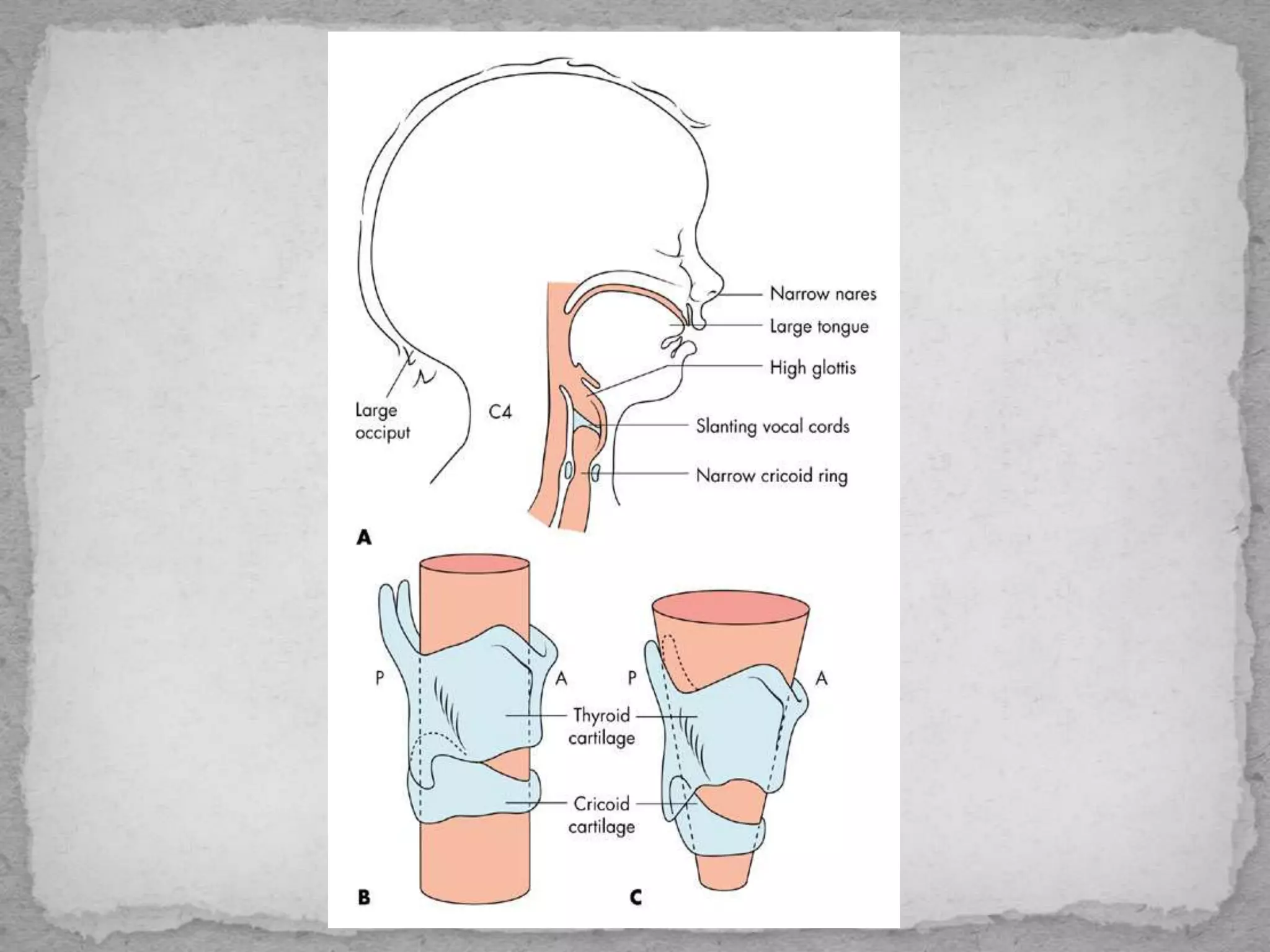

This document provides guidance on managing pediatric airways. It discusses signs of airway instability including retractions, nasal flaring, and head bobbing. It describes pediatric airway anatomy and how it differs from adults. The document outlines how to open and maintain an airway manually or with devices. It also discusses techniques for bag-mask ventilation and intubation in pediatric patients, as well as dealing with difficult airways. Complications of airway management are addressed.

![ INDICATIONS

Respiratory

■ Apnea.

■ Acute respiratory failure (PaO2 < 50 mm Hg in patient with fraction of inspired

oxygen [FIO2] > 0.5 and PaCO2 > 55 mm Hg).

■ Need to control oxygen delivery (e.g. institution of positive end-expiratory

pressure [PEEP], accurate delivery of FIO2 > 0.5)

■ Need to control ventilation (e.g. to decrease work of breathing, to control

PaCO2, to provide muscle relaxation).

Neurologic

■ Inadequate chest wall function (e.g. in patient with Guillain- Barré syndrome,

poliomyelitis).

■ Absence of protective airway reflexes (e.g. cough, gag).

■ Glasgow Coma Score ≤ 8.

Airway

■ Upper airway obstruction.

■ Infectious processes (e.g. epiglottis, croup).

■ Trauma to the airway.

■ Burns (concern for airway edema).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pediatricairwaymanagement-150125035309-conversion-gate01/75/Pediatric-airway-management-57-2048.jpg)