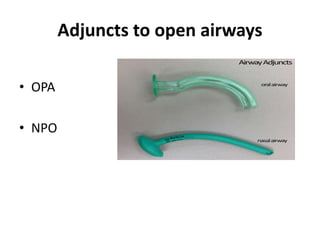

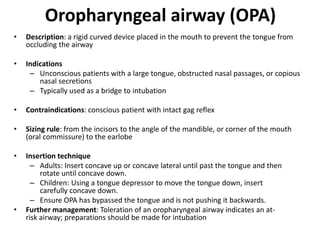

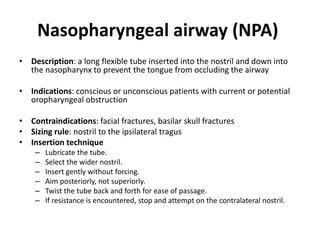

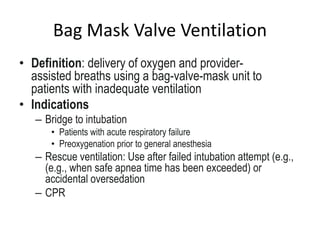

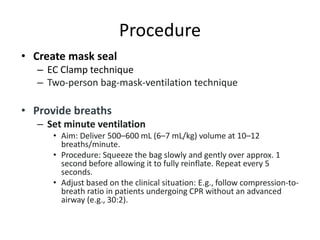

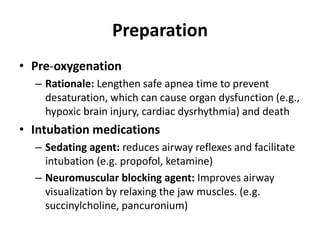

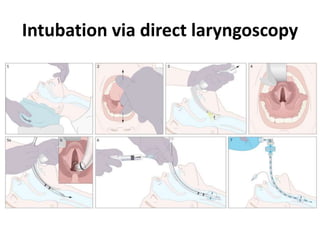

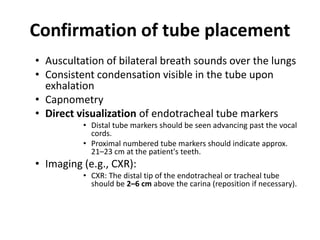

This document discusses airway management. It covers airway anatomy, assessment of patent and compromised airways, causes of compromise, recognition through listening, looking and feeling, and basic interventions to open the airway including head tilt, chin lift, jaw thrust, suctioning, and use of oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways. It also discusses bag mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation including indications, preparation, technique and confirmation of proper placement.