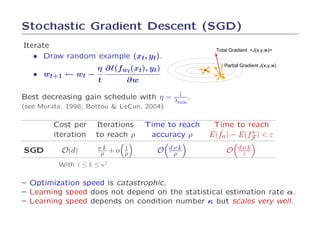

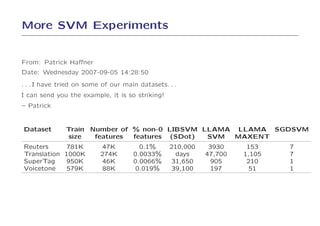

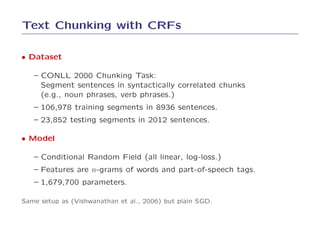

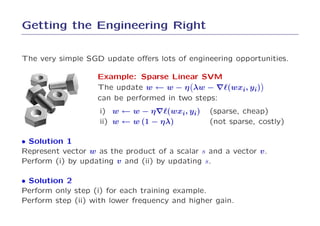

1. SGD was tested on simple learning problems like support vector machines and conditional random fields and showed competitive performance compared to specialized solvers.

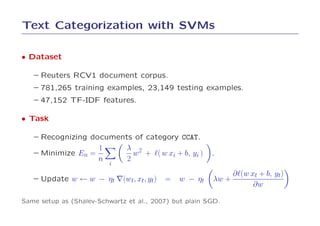

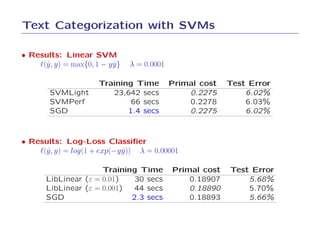

2. On text categorization with SVMs, SGD achieved the same test error as SVMLight and SVMPerf but was over 100 times faster to train.

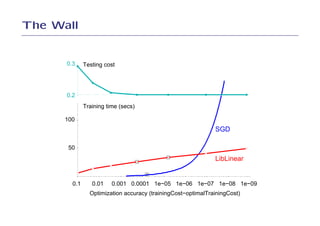

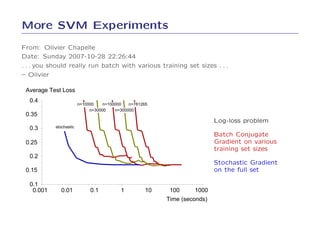

3. On log-loss classification, SGD achieved a slightly better test error than LibLinear and was over 10 times faster to train.

4. The results demonstrate that SGD can optimize simple learning problems very efficiently without the need for more complex optimization methods.

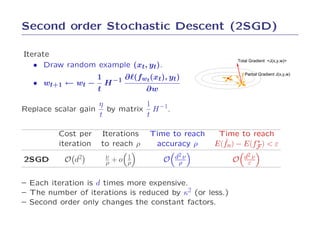

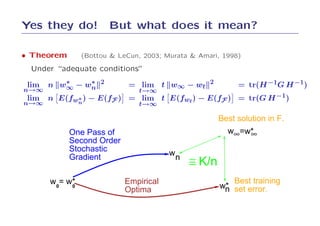

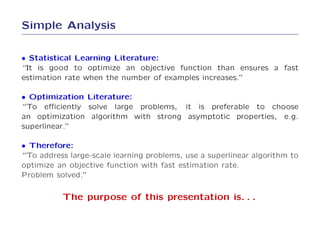

![Quantities of Interest

• Empirical Hessian at the empirical optimum wn.

n

∂ 2En 1 ∂ 2ℓ(fn(xi), yi)

H = (fwn ) =

∂w2 n ∂w2

i=1

• Empirical Fisher Information matrix at the empirical optimum wn.

n

1 ∂ℓ(fn(xi), yi) ∂ℓ(fn(xi), yi) ′

G =

n ∂w ∂w

i=1

• Condition number

We assume that there are λmin, λmax and ν such that

– trace GH −1 ≈ ν .

– spectrum H ⊂ [λmin, λmax].

and we define the condition number κ = λmax/λmin.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bottou-nips-07-tutorial-110512223035-phpapp02/85/NIPS2007-learning-using-many-examples-22-320.jpg)