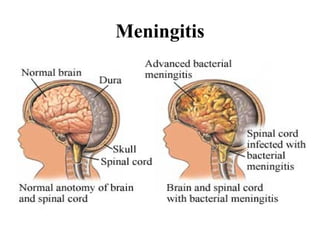

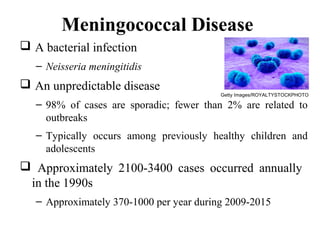

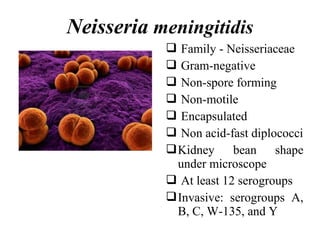

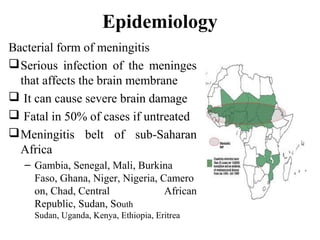

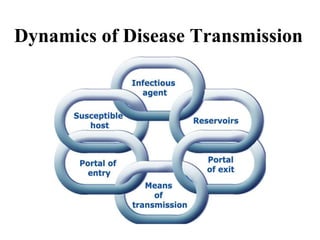

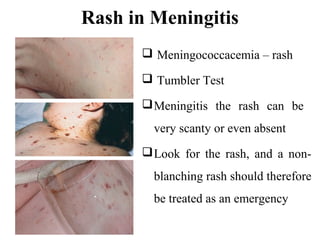

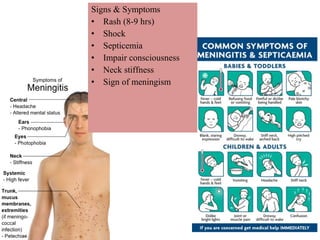

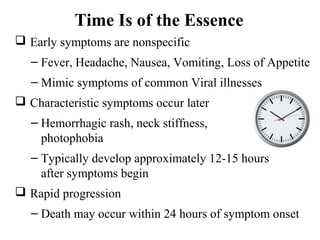

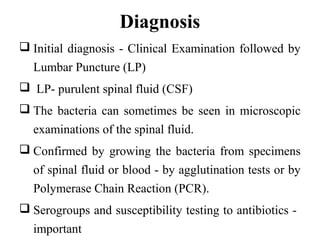

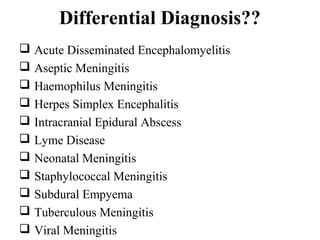

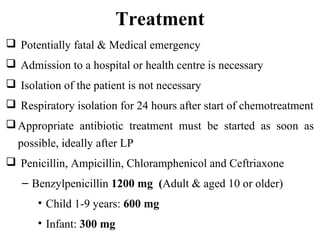

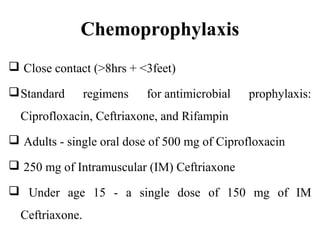

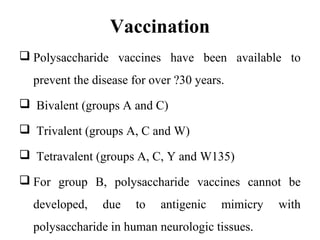

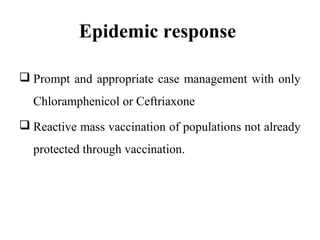

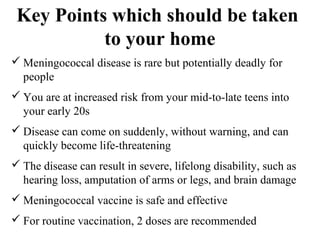

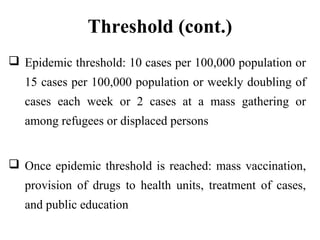

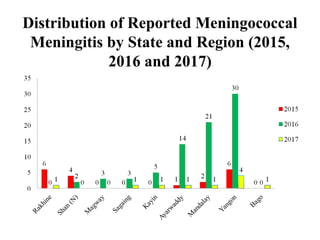

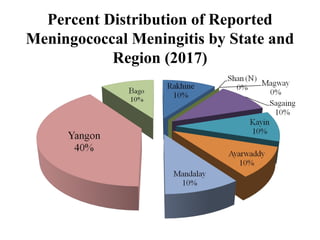

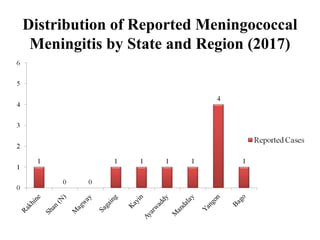

This document provides information on meningococcal meningitis, a potentially deadly bacterial infection. It discusses the causal organism, Neisseria meningitidis, its transmission through respiratory droplets, and symptoms including fever, neck stiffness, and rash. Prompt treatment with antibiotics is important but even so 10-15% of patients may die and 20% may suffer long-term disabilities. Vaccines can help prevent infections from some common strains. During outbreaks, identifying cases, tracing contacts, vaccinating at-risk groups, and communicating findings are important control measures.