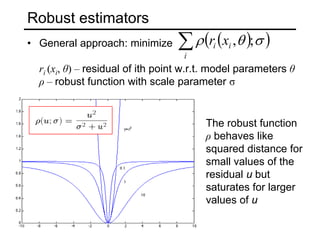

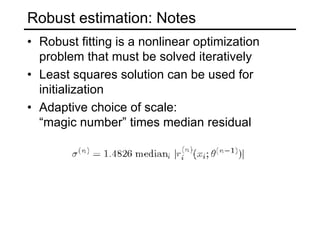

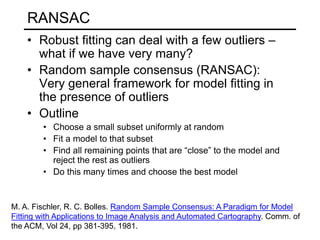

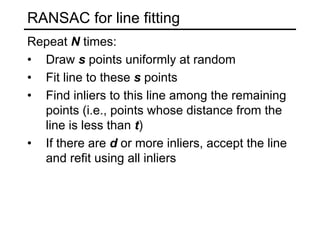

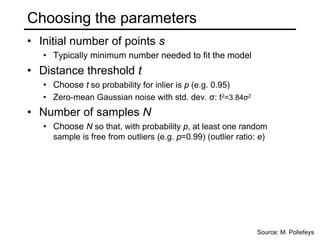

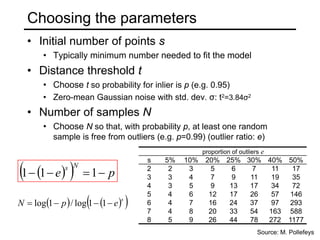

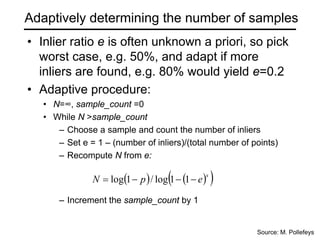

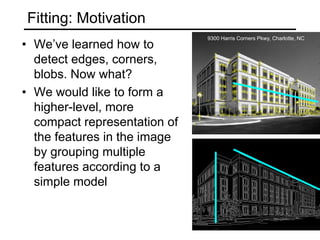

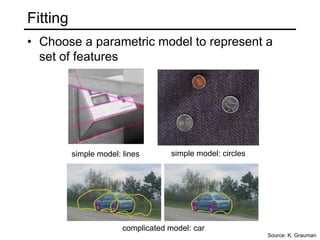

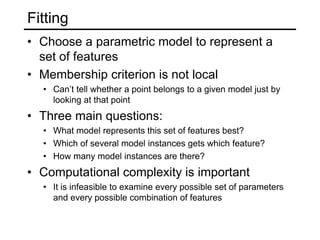

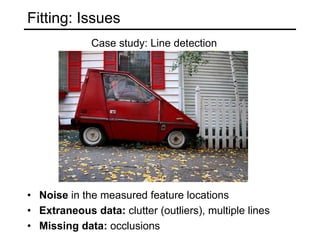

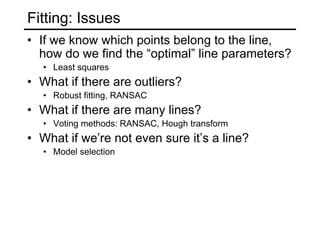

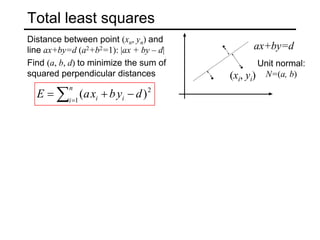

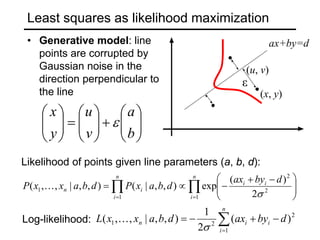

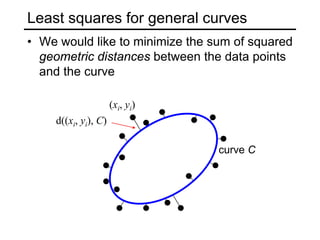

This document discusses techniques for fitting parametric models to sets of image features. It begins by introducing the concept of fitting, where a simple parametric model (like a line or circle) is used to represent multiple detected features. It describes how fitting involves choosing the best model, assigning features to model instances, and determining the number of instances. The document then discusses specific issues that arise, such as noise, outliers, missing data, and model selection. It presents techniques for line fitting, including least squares, total least squares, and robust methods like RANSAC. It also discusses fitting general curves and conics using least squares approaches.

![Least squares line fitting

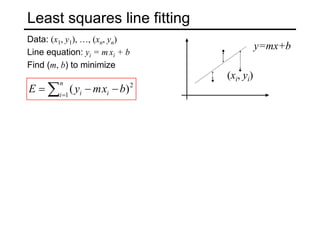

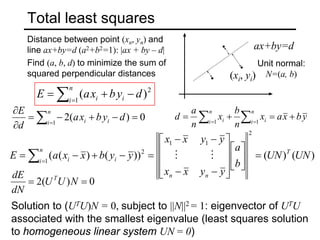

Data: (x1, y1), …, (xn, yn)

Line equation: yi = m xi + b

Find (m, b) to minimize

0

2

2 =

−

= Y

X

XB

X

dB

dE T

T

[ ]

)

(

)

(

)

(

2

)

(

)

(

1

1

1

2

2

1

1

1

2

XB

XB

Y

XB

Y

Y

XB

Y

XB

Y

XB

Y

b

m

x

x

y

y

b

m

x

y

E

T

T

T

T

n

n

n

i i

i

+

−

=

−

−

=

−

=

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎟

⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎜

⎝

⎛

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

= ∑=

M

M

M

Normal equations: least squares solution to

XB=Y

∑=

−

−

=

n

i i

i b

x

m

y

E 1

2

)

(

(xi, yi)

y=mx+b

Y

X

XB

X T

T

=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec08fitting-220218163004/85/Lec08-fitting-8-320.jpg)

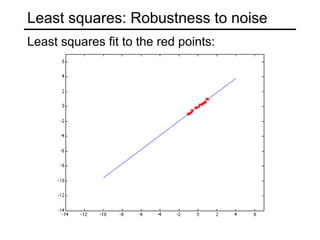

![Least squares for conics

• Equation of a general conic:

C(a, x) = a · x = ax2 + bxy + cy2 + dx + ey + f = 0,

a = [a, b, c, d, e, f],

x = [x2, xy, y2, x, y, 1]

• Minimizing the geometric distance is non-linear even for

a conic

• Algebraic distance: C(a, x)

• Algebraic distance minimization by linear least squares:

0

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

f

e

d

c

b

a

y

x

y

y

x

x

y

x

y

y

x

x

y

x

y

y

x

x

n

n

n

n

n

n

M

O

M](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec08fitting-220218163004/85/Lec08-fitting-17-320.jpg)