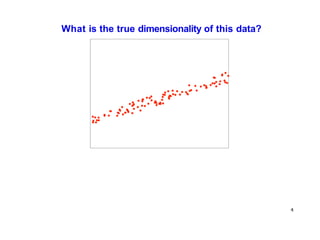

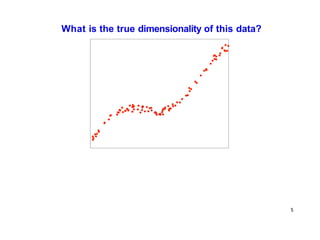

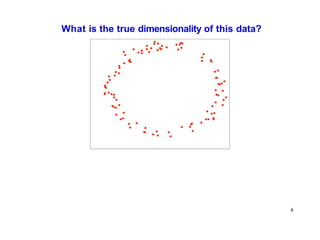

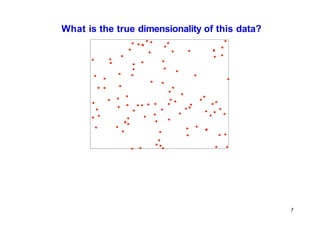

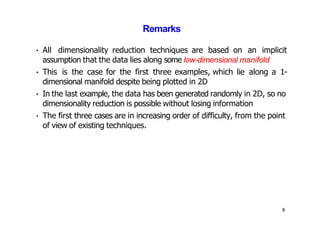

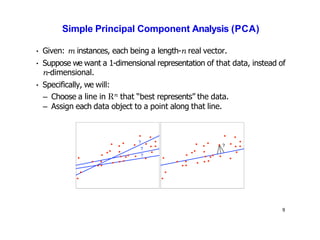

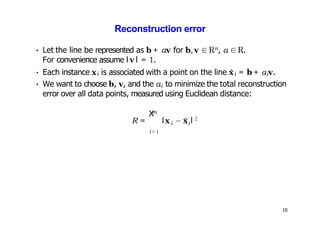

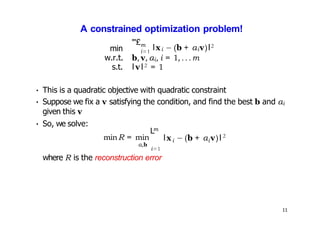

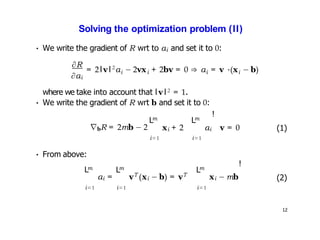

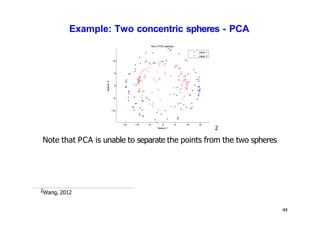

- Dimensionality reduction techniques assign instances to vectors in a lower-dimensional space while approximately preserving similarity relationships. Principal component analysis (PCA) is a common linear dimensionality reduction technique.

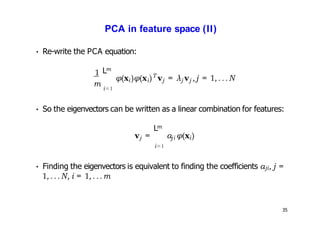

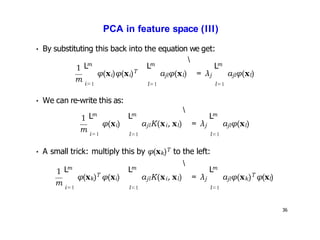

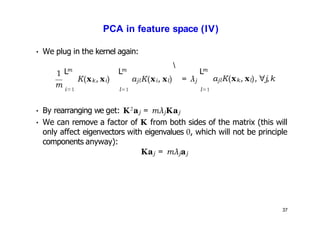

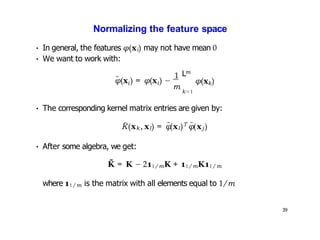

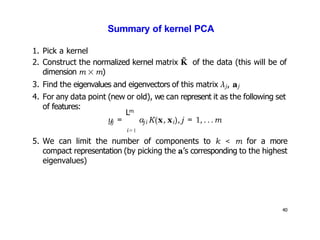

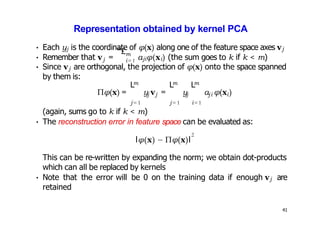

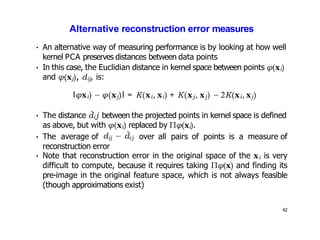

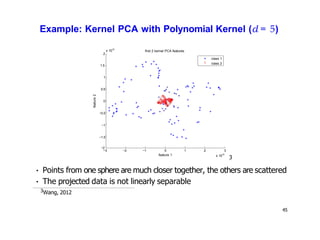

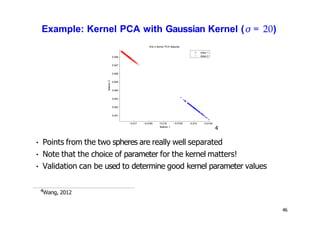

- Kernel PCA performs PCA in a higher-dimensional feature space implicitly defined by a kernel function. This allows PCA to find nonlinear structure in data. Kernel PCA computes the principal components by finding the eigenvectors of the normalized kernel matrix.

- For a new data point, its representation in the lower-dimensional space is given by projecting it onto the principal components in feature space using the kernel trick, without explicitly computing features.

![PCA vs Locally Linear Embedding

[Saul, L. K., & Roweis, S. T. (2000).

embedding.]

50

An introduction to locally linear](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ml-lecture13-230811135539-eb87decd/85/machine-learning-pptx-50-320.jpg)