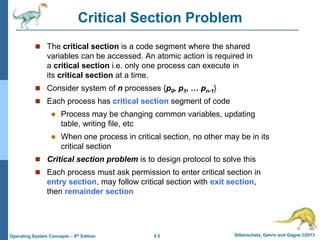

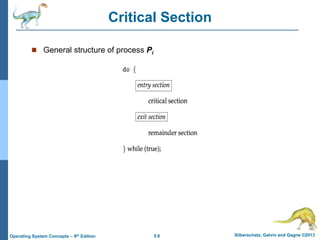

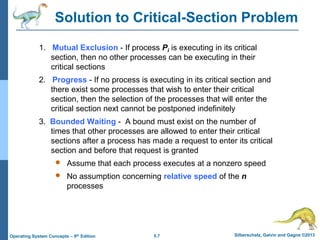

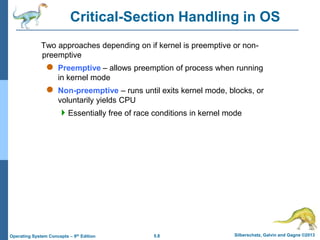

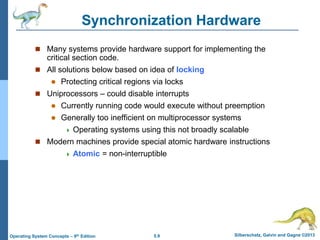

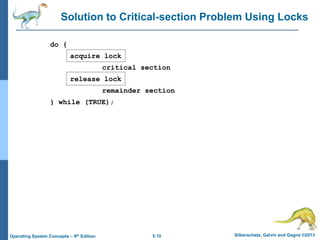

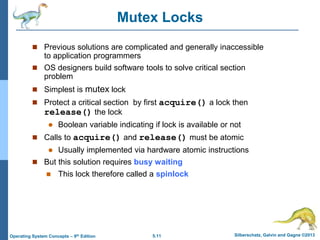

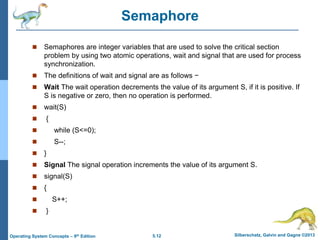

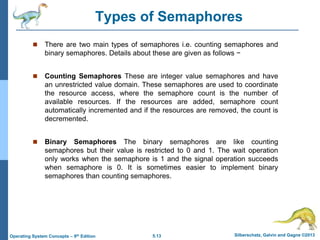

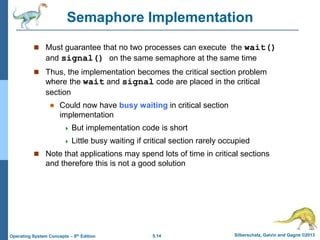

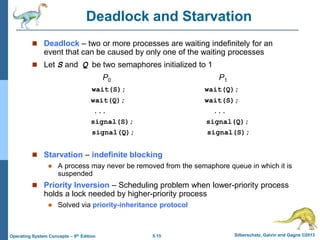

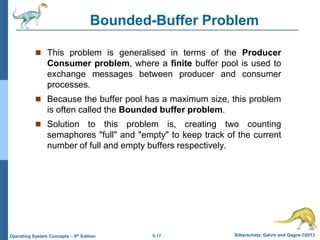

This chapter discusses process synchronization and solving the critical section problem. It introduces Peterson's solution to the critical section problem and other synchronization methods like mutex locks, semaphores, and monitors. Classical synchronization problems covered include the bounded buffer problem, dining philosophers problem, and readers-writers problem. The chapter aims to present concepts of process synchronization and tools to solve synchronization issues.