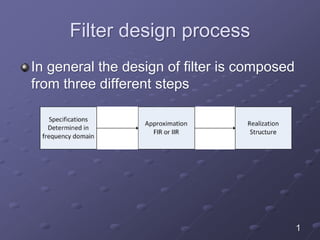

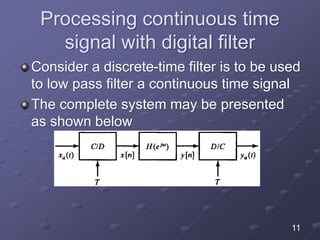

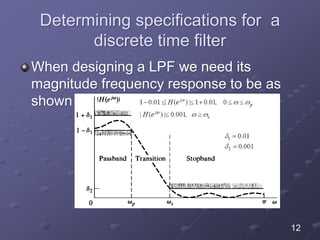

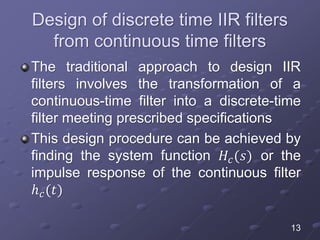

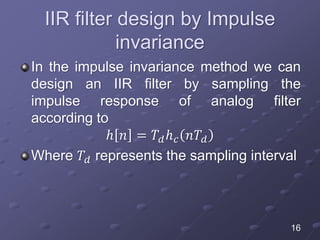

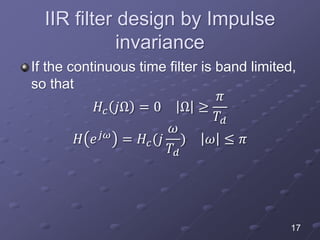

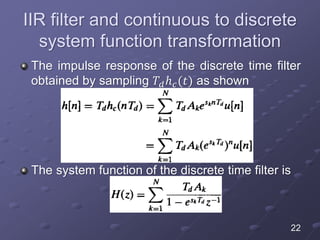

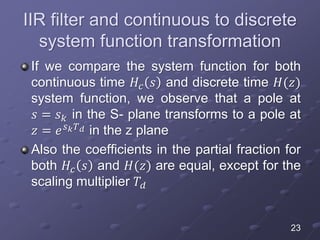

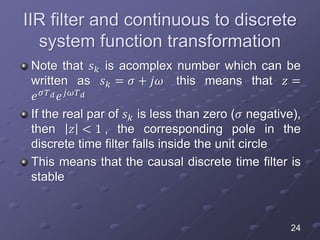

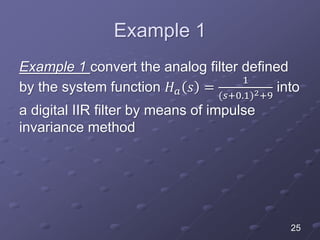

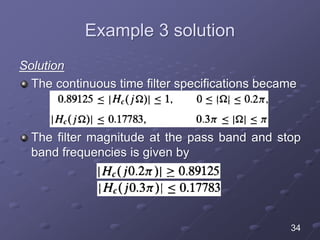

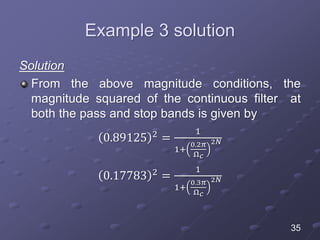

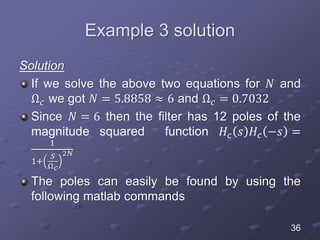

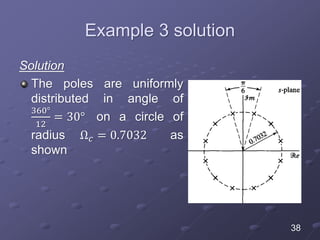

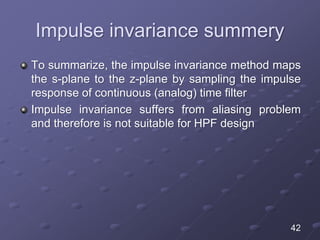

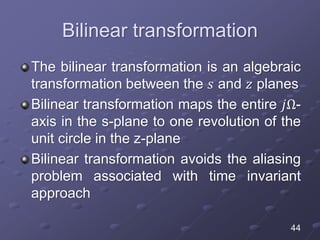

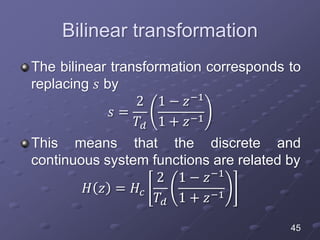

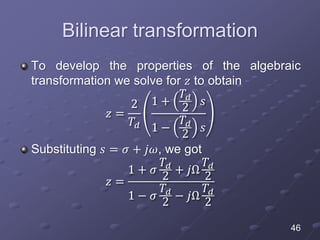

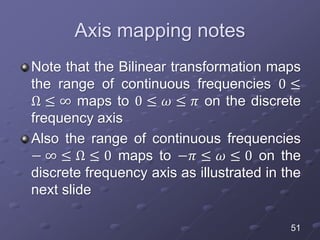

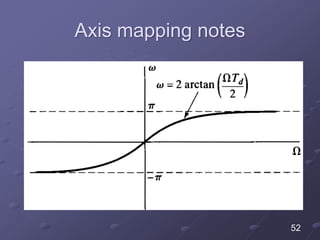

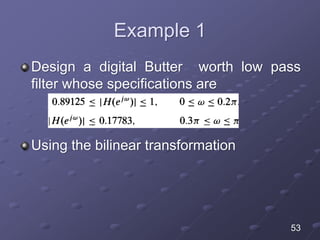

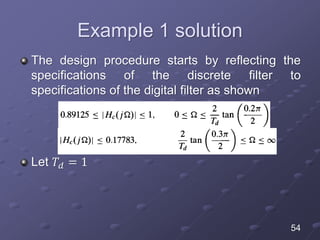

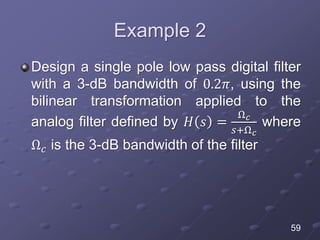

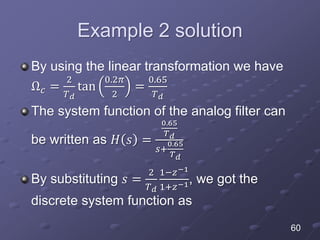

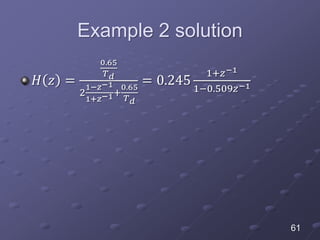

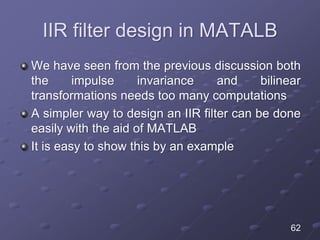

The document details the filter design process, highlighting three main steps: selecting appropriate filter design techniques based on desired characteristics, choosing between FIR and IIR filters based on phase distortion tolerance and complexity, and specifying discrete-time filter designs from continuous-time analog filters. It discusses methods for determining filter coefficients and emphasizes the stability and causality in filter design, alongside practical issues such as aliasing. The document also covers specific examples of designing filters using methods like impulse invariance and bilinear transformation.

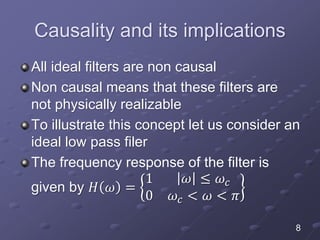

![Causality and its implications

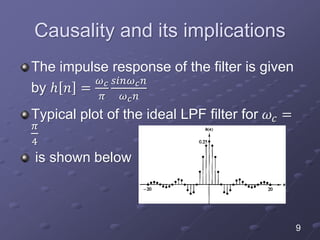

From the plot of ℎ[𝑛] it is clear that ℎ 𝑛 ≠

0 for 𝑛 < 0 which means that the filter is

not causal

If the filter is not causal this means that the

filter output samples 𝑦[𝑛] depends on the

future values of the input 𝑥[𝑛 + 1], 𝑥[𝑛 +

2] which is impossible to estimate

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filterdesigntechniquesch7iir-160924205208/85/Filter-design-techniques-ch7-iir-10-320.jpg)

![Example 3 solution

𝑎 = 1

b=[68.399 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1]

[𝑧 𝑝 𝑘] = 𝑡𝑓2𝑧𝑝(𝑎, 𝑏)

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filterdesigntechniquesch7iir-160924205208/85/Filter-design-techniques-ch7-iir-37-320.jpg)

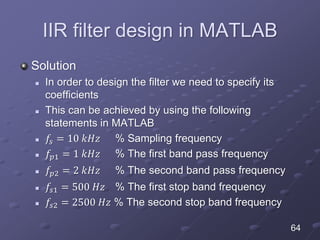

![IIR filter design in MATLAB

𝑅𝑝 = 1 𝑑𝐵 % The ripple in the pass band

𝑅 𝑆 = 60 𝑑𝐵 % The attenuation in the stop band

The filter order and normalized frequencies can be

computed by using the following statement

[𝑛, 𝑊𝑛] = 𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑡𝑜𝑟𝑑

𝑓𝑝1 𝑓𝑝2

𝑓𝑠

,

𝑓𝑠1 𝑓𝑠2

𝑓𝑠

, 𝑅 𝑝, 𝑅 𝑠

The filter coefficients can be computed from the

following statements

𝑏, 𝑎 = 𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑛, 𝑊𝑛 ;

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filterdesigntechniquesch7iir-160924205208/85/Filter-design-techniques-ch7-iir-65-320.jpg)

![IIR filter design in MATLAB

More examples to design IIR filter is by the use of these

statements

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟(𝑛, 𝑊𝑛, 𝑜𝑝𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠)

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑏𝑢𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟(5,0.4); % Lowpass Butterworth

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑏𝑦1(𝑛, 𝑅𝑝, 𝑊𝑛, 𝑜𝑝𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠)

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑏𝑦1(4,1, [0.4 0.7]); % Bandpass Chebyshev Type I

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑏𝑦2(𝑛, 𝑅𝑠, 𝑊𝑛, 𝑜𝑝𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠)

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑐ℎ𝑒𝑏𝑦2(6,60,0.8, ′ℎ𝑖𝑔ℎ′); % Highpass Chebyshev Type II

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑒𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑝(𝑛, 𝑅𝑝, 𝑅𝑠, 𝑊𝑛, 𝑜𝑝𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠)

[𝑏, 𝑎] = 𝑒𝑙𝑙𝑖𝑝(3,1,60, [0.4 0.7], ′𝑠𝑡𝑜𝑝′); % Bandstop elliptic

66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filterdesigntechniquesch7iir-160924205208/85/Filter-design-techniques-ch7-iir-66-320.jpg)