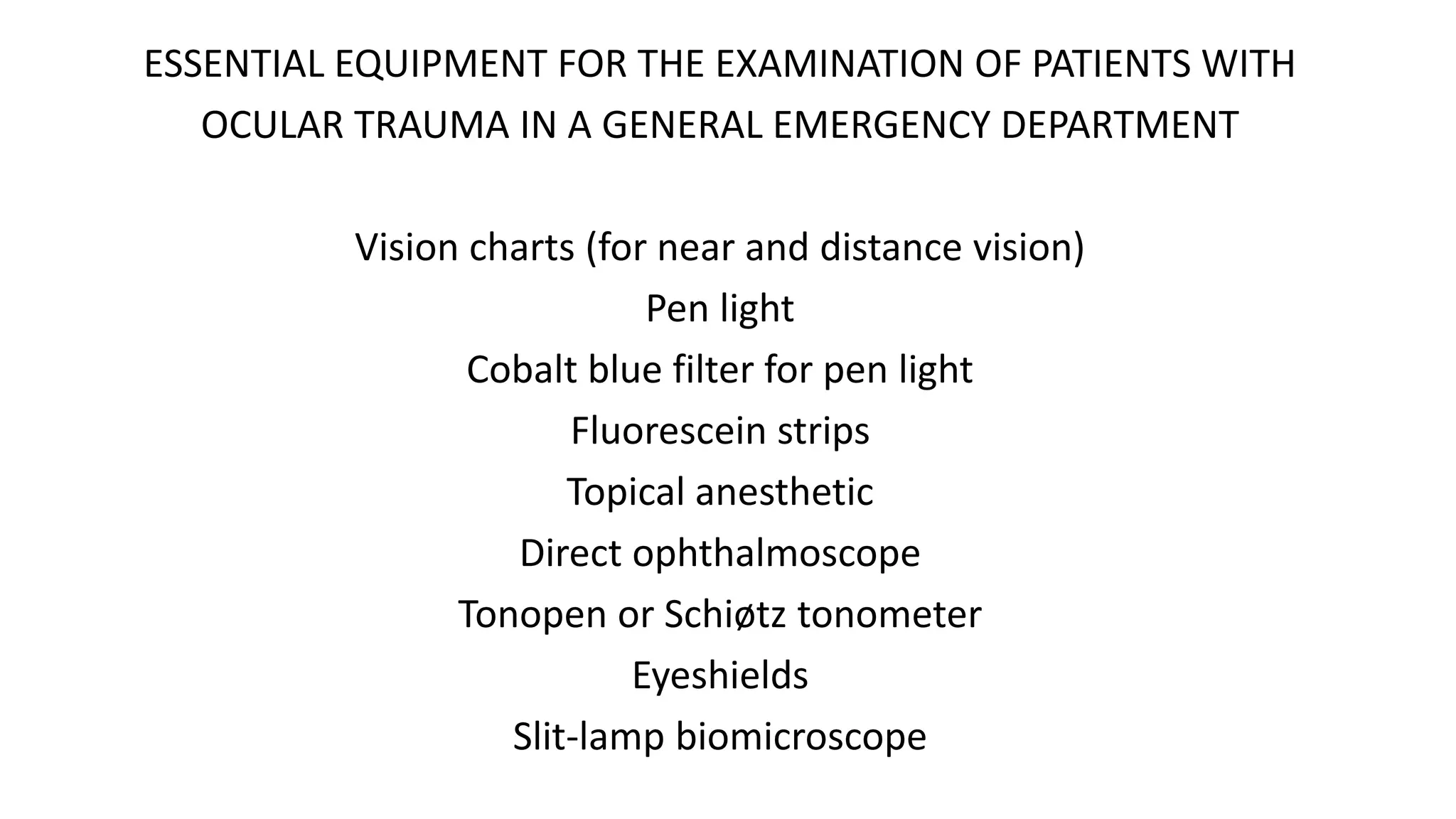

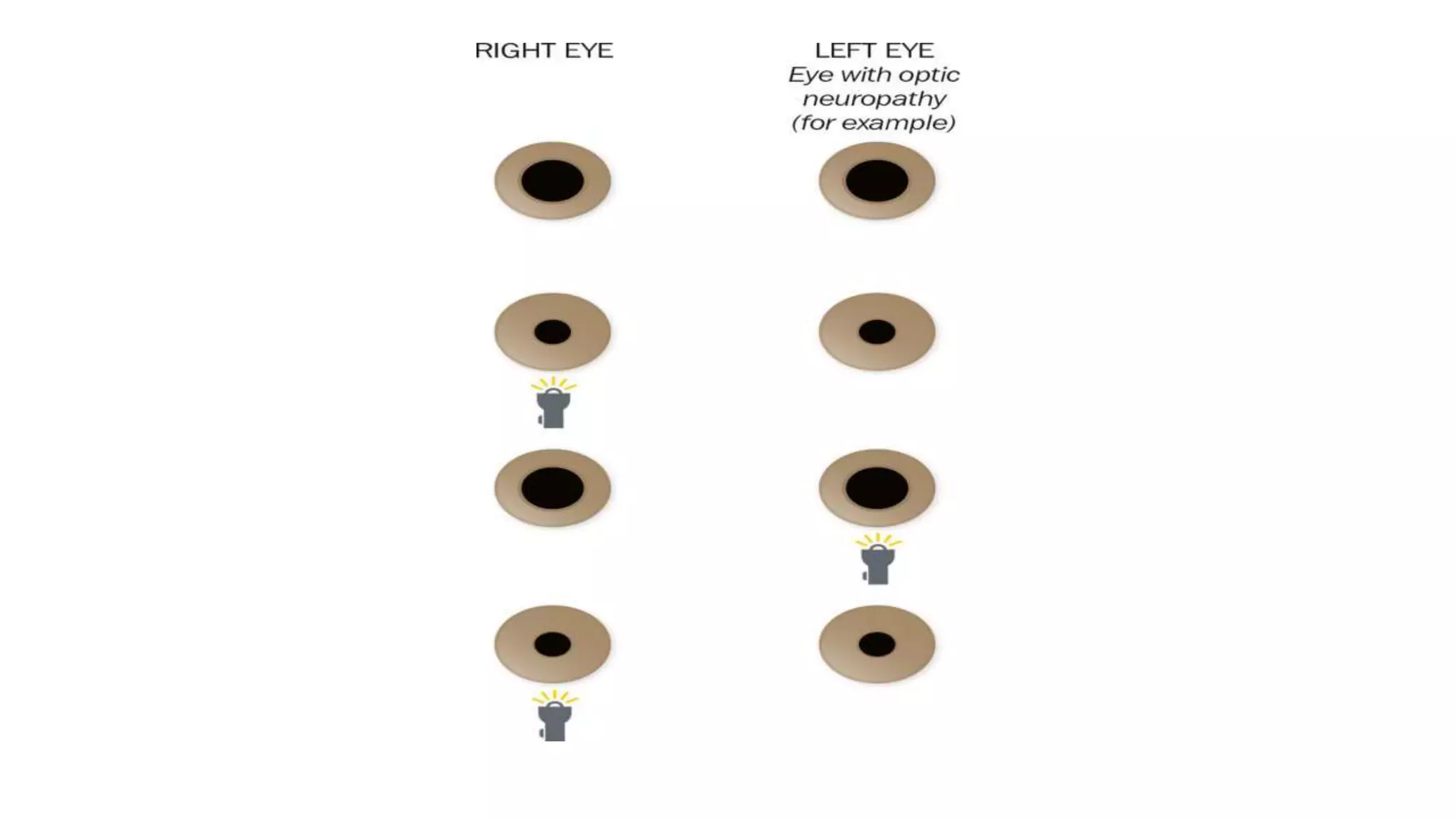

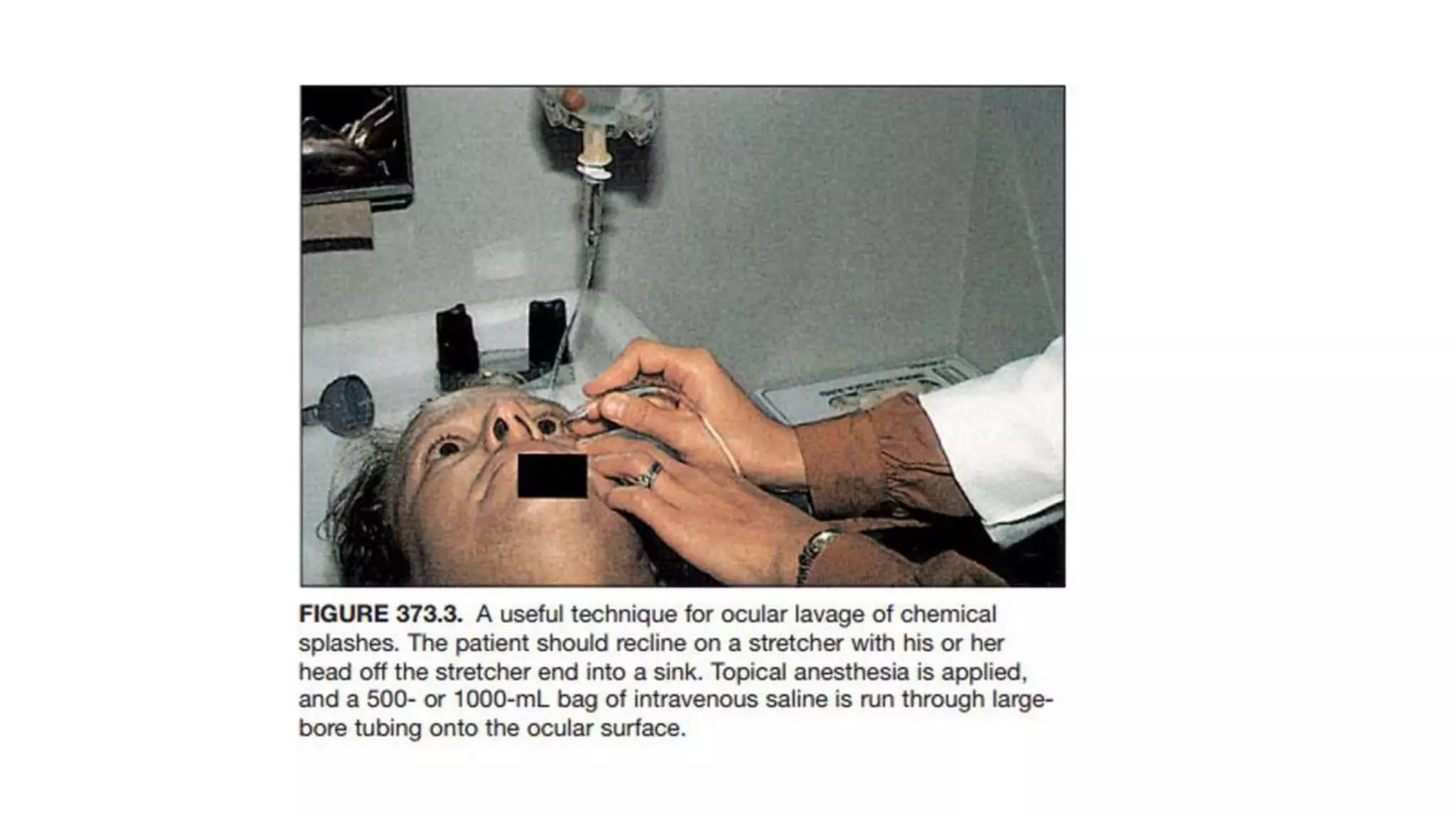

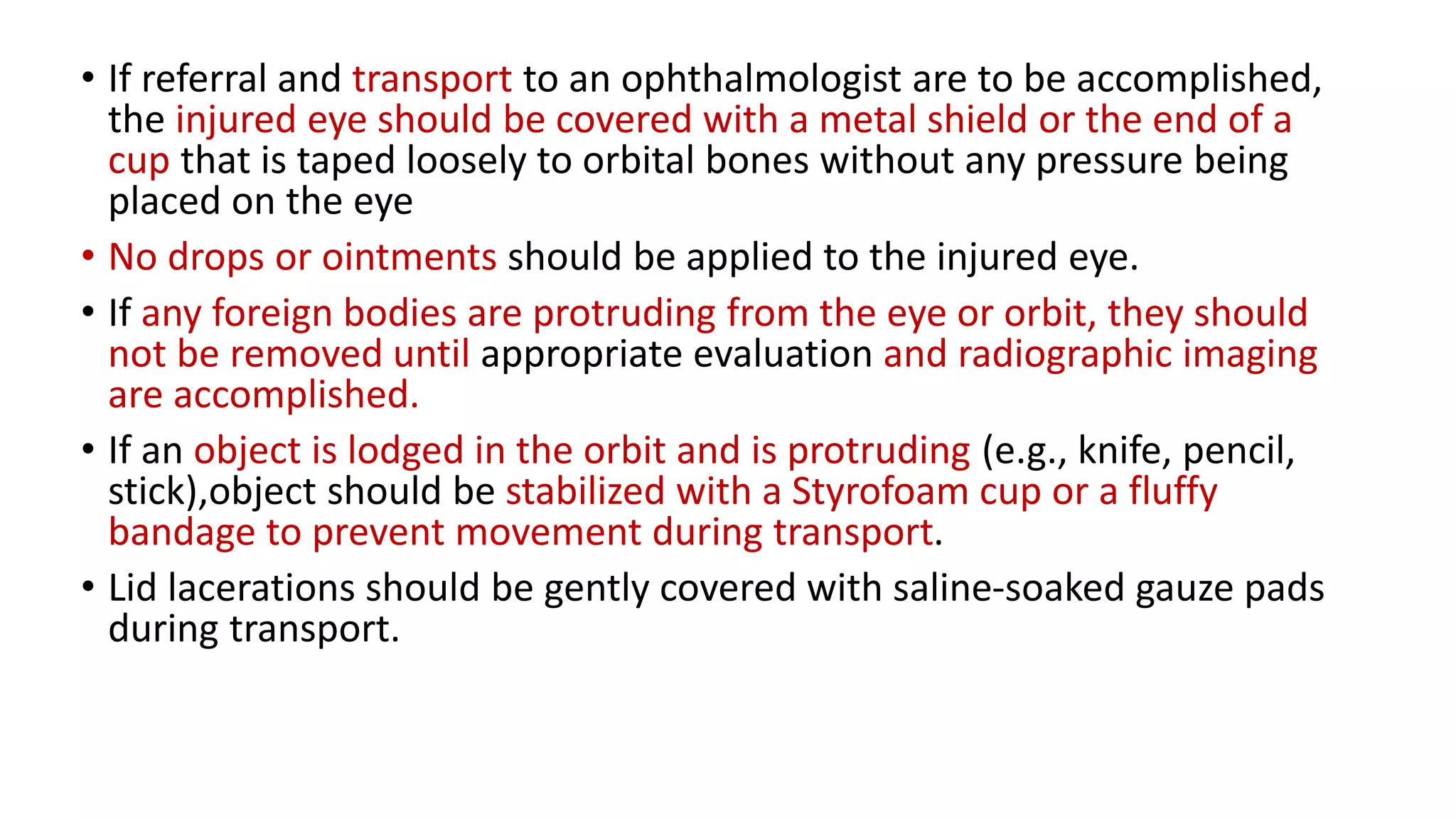

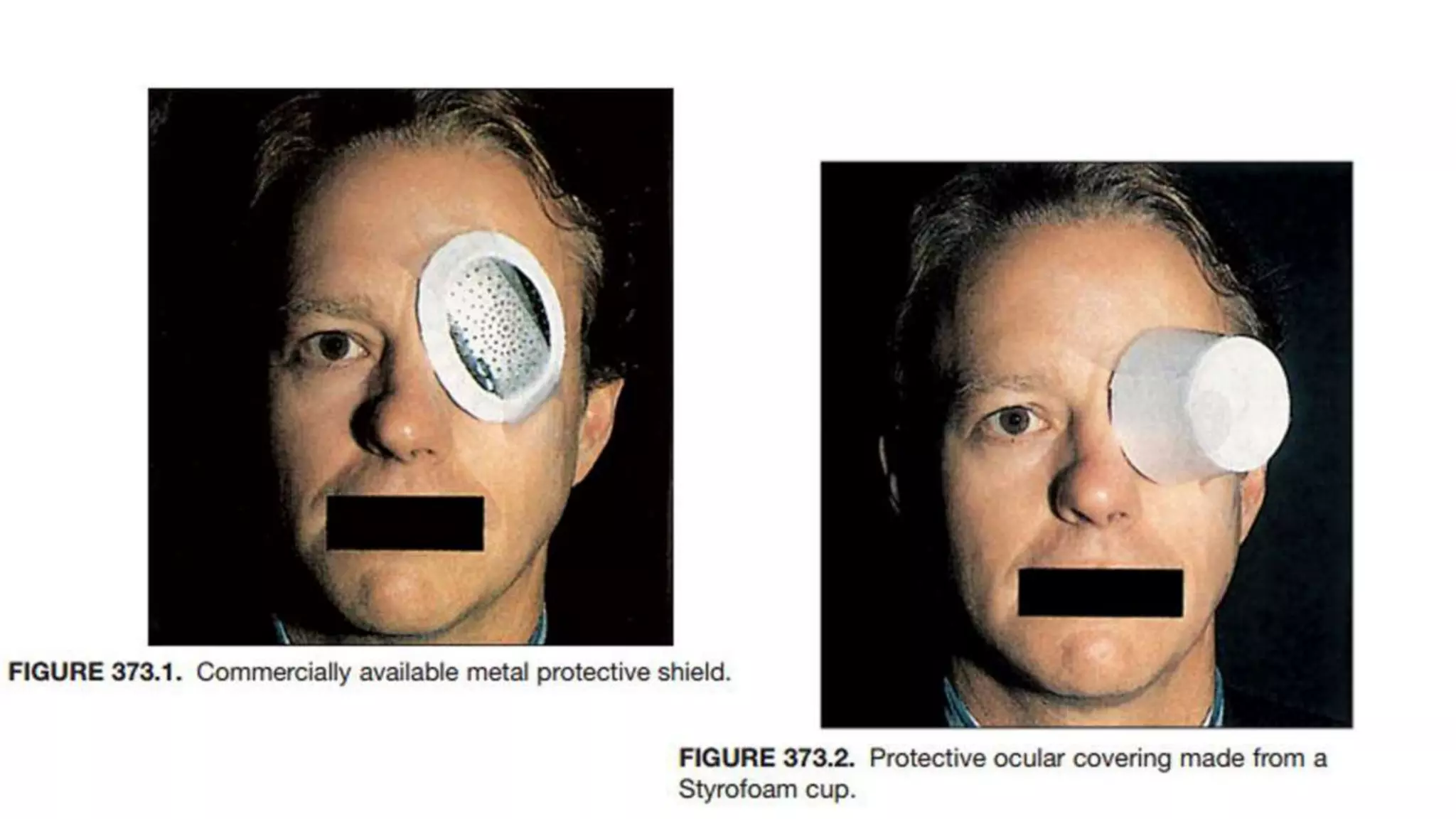

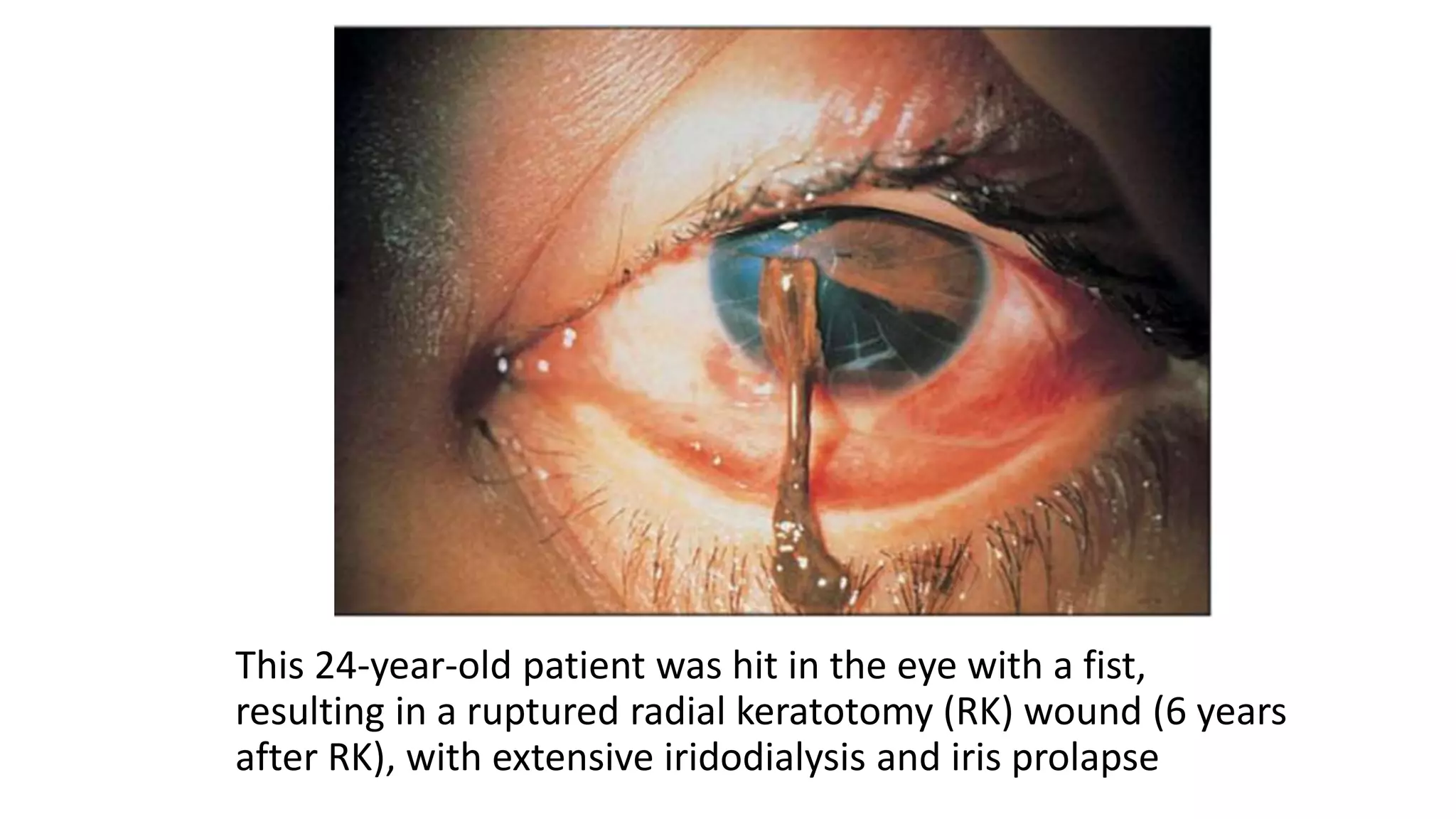

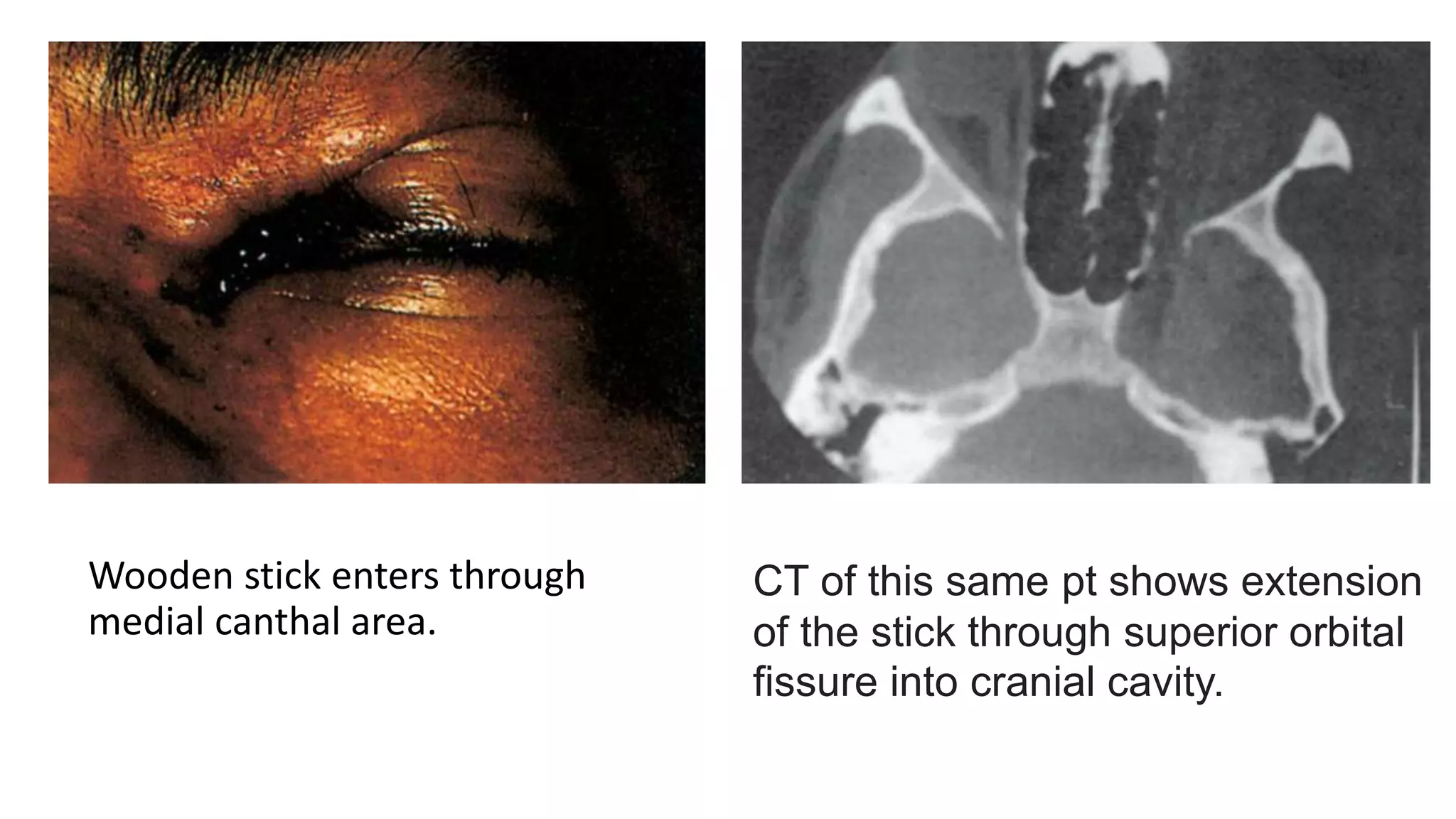

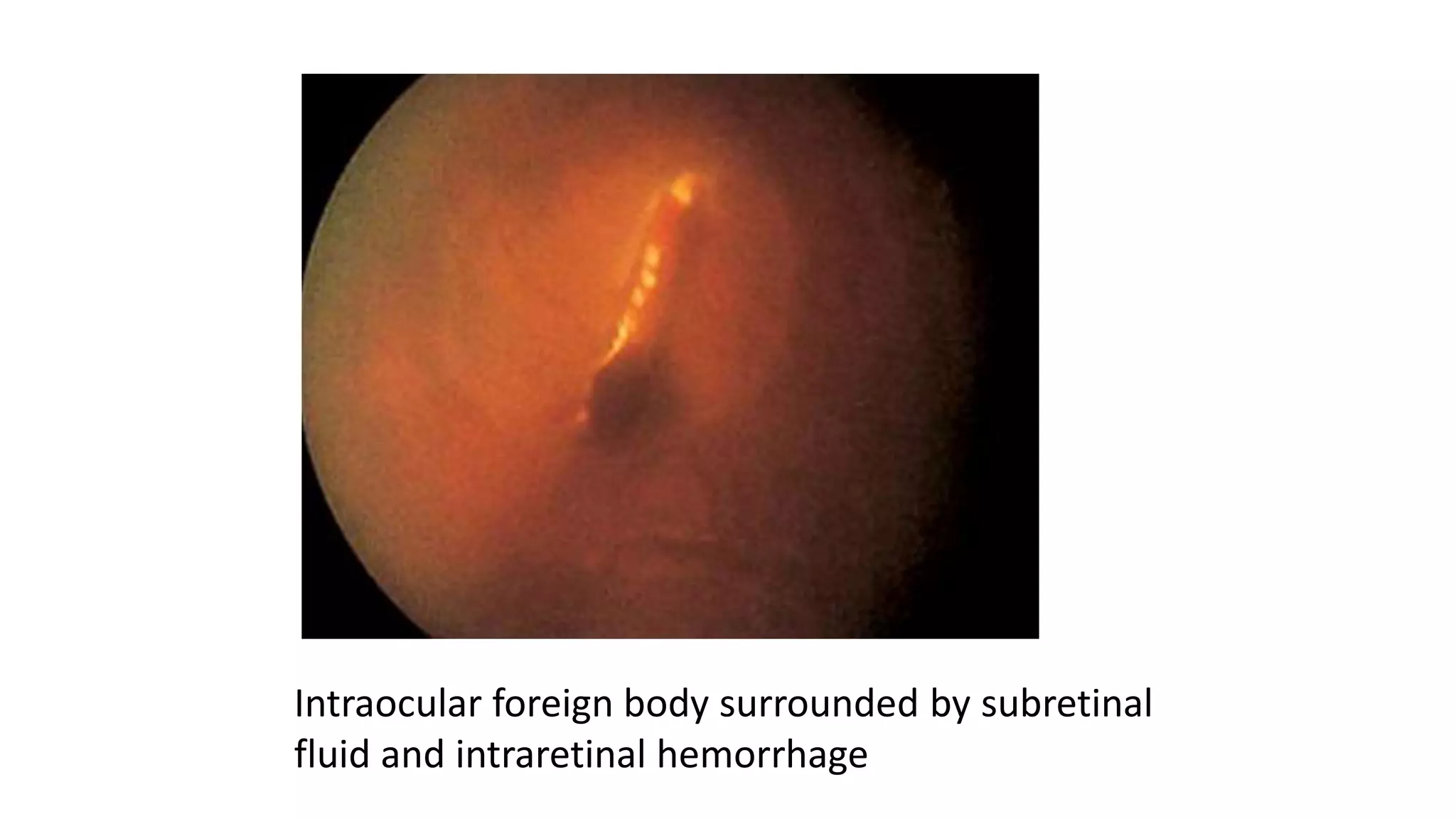

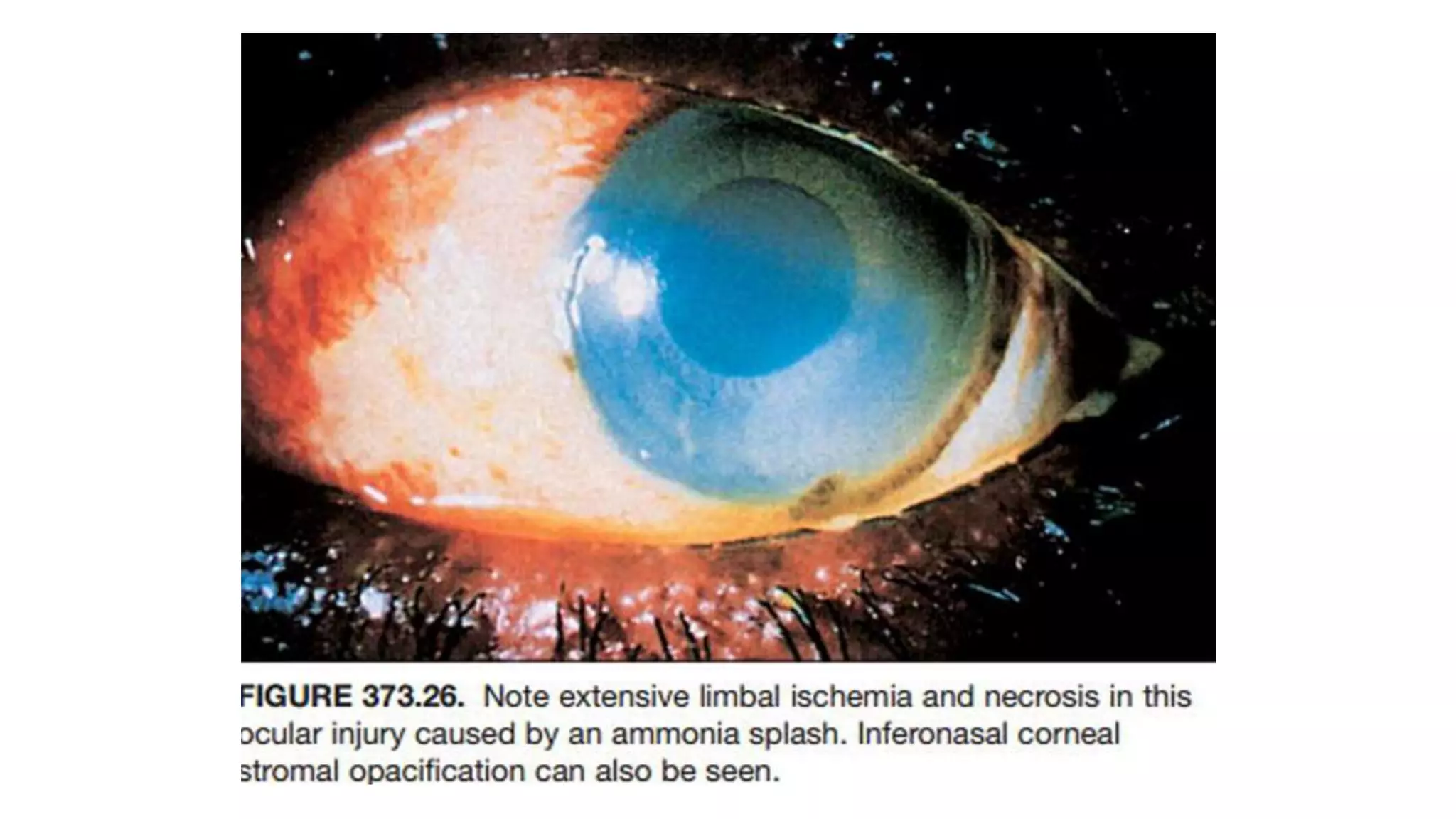

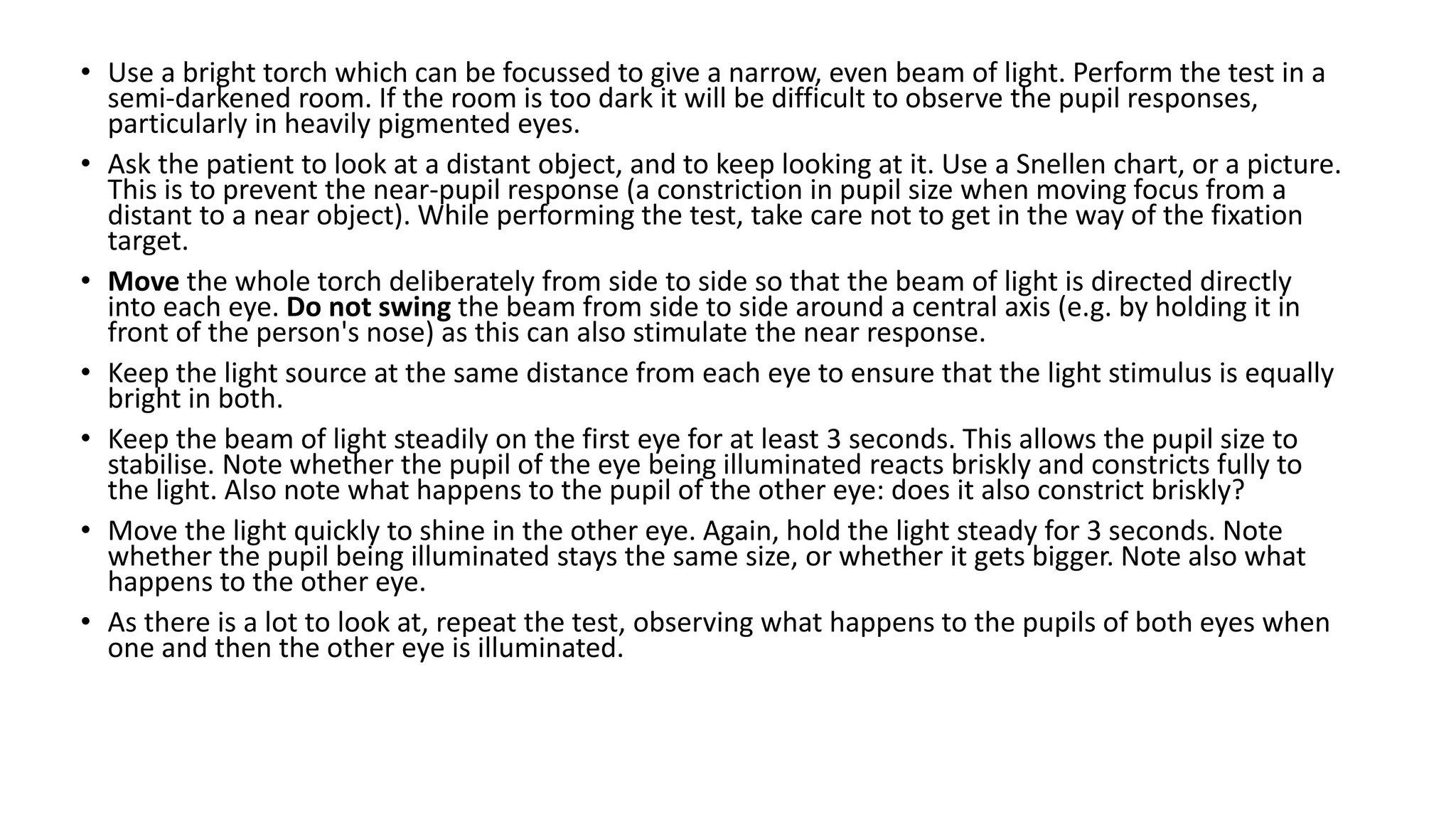

This document provides guidelines for evaluating and initially managing patients with ocular and adnexal trauma. It outlines the essential steps in the emergency department, which include stabilizing life-threatening injuries, lavaging the eyes if a chemical injury occurred, obtaining medical and ocular histories, and performing an eye examination. The document describes the necessary equipment, how to assess visual acuity, external features, ocular motility, pupils, anterior and posterior segments, and intraocular pressure. It provides referral criteria and recommendations for care, transport, and follow up by ophthalmologists.