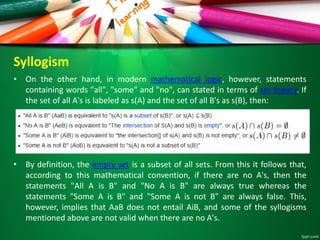

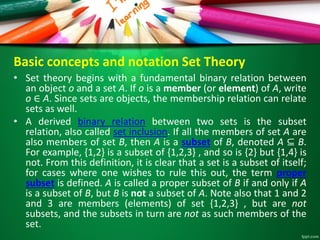

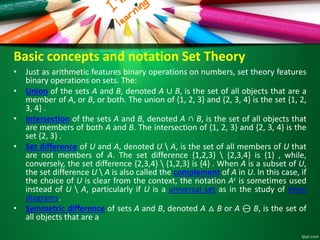

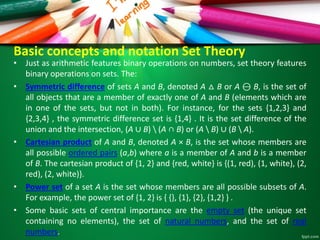

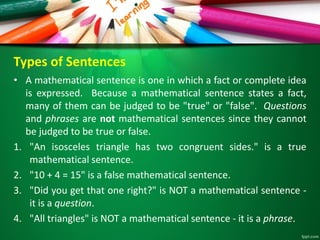

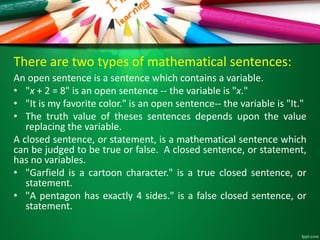

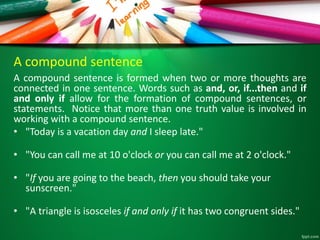

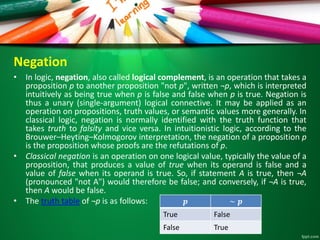

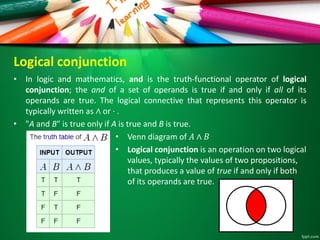

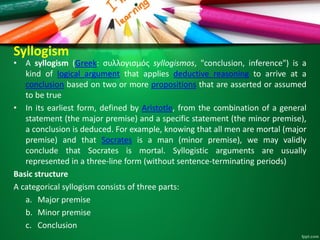

This document provides an overview of mathematical logic and set theory concepts. It discusses topics such as mathematical logic and its subfields, basic set theory concepts like membership and subsets, set operations like union and intersection, and logical concepts like negation, conjunction, and syllogisms. It also explains logical form and provides examples of open and closed sentences as well as categorical and compound sentences.

![Syllogism

• The premises and conclusion of a syllogism can be any of four types, which

are labeled by letters[9] as follows. The meaning of the letters is given by the

table:

• In Analytics, Aristotle mostly uses the letters A, B and C (actually, the Greek

letters alpha, beta and gamma) as term place holders, rather than giving

concrete examples, an innovation at the time. It is traditional to use is rather

than are as the copula, hence All A is B rather than All As are Bs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pertemuanke-11-151214132008/85/English-for-Math-Pertemuan-ke-11-16-320.jpg)