The document provides information on various mathematical concepts including polynomials, abstract algebra, groups, rings, and fields. Some key points:

- A polynomial is an expression consisting of variables and constants with whole number exponents, such as x2 + 2x - 3.

- Abstract algebra generalizes concepts like sets, binary operations, identity elements, and inverse elements from elementary algebra.

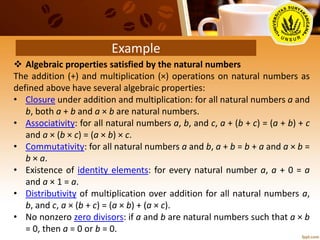

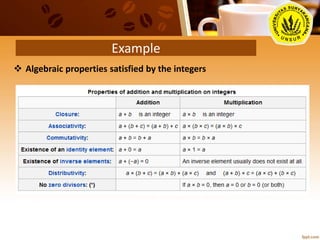

- A group combines a set and single binary operation that satisfies properties like closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility. The integers under addition form a group.

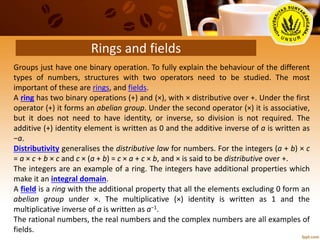

- Rings have two binary operations where one forms an abelian group and the other is associative with distributivity. The integers are a ring.