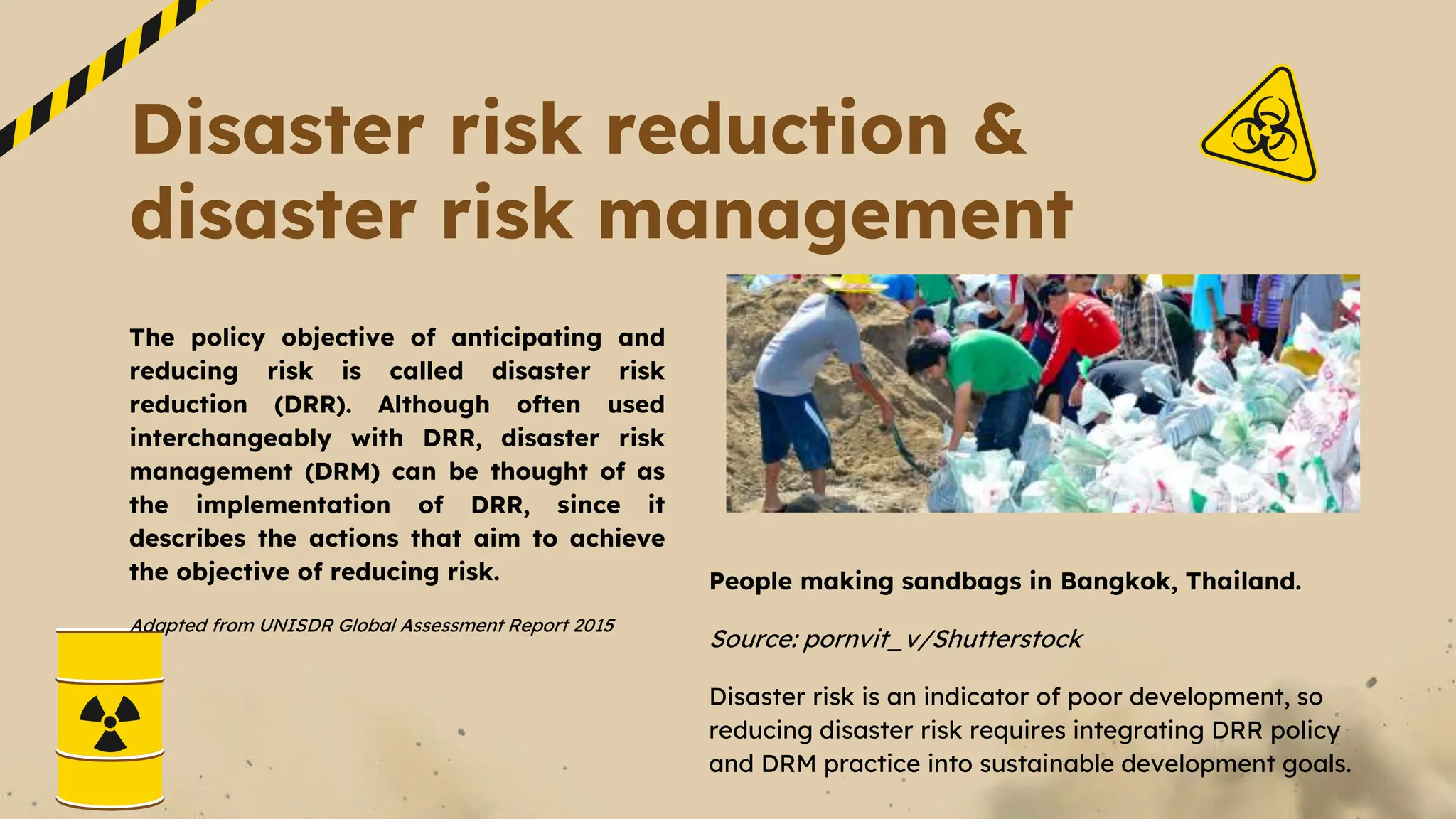

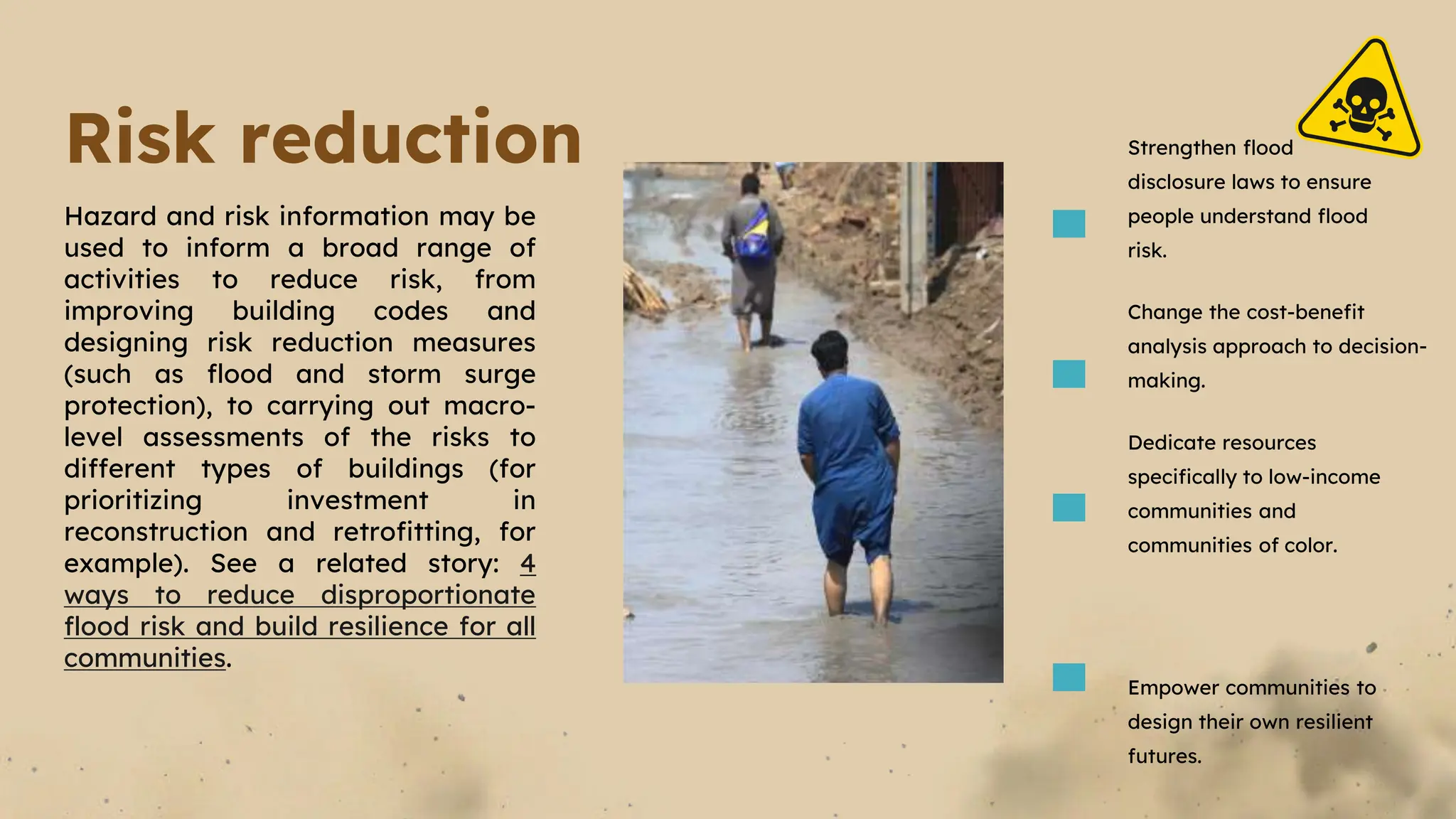

The document discusses disaster risk reduction (DRR) and disaster risk management (DRM). It defines DRR as anticipating and reducing risk through policy, while DRM describes implementing DRR through actions to reduce risk. Reducing disaster risk requires integrating DRR and DRM into development goals to address the drivers of risk. The document outlines key aspects of DRR and DRM, including prevention, mitigation, risk transfer, and preparedness activities. It emphasizes the importance of understanding hazards, exposure, and vulnerability through risk identification and analysis to inform risk reduction efforts. However, more work is still needed to reduce risks from urbanization and climate change, as risks are increasing faster than being reduced in many places.